The Mind Behind Metaphor and Persona 5 Still Has Hope For the Art of Video Games

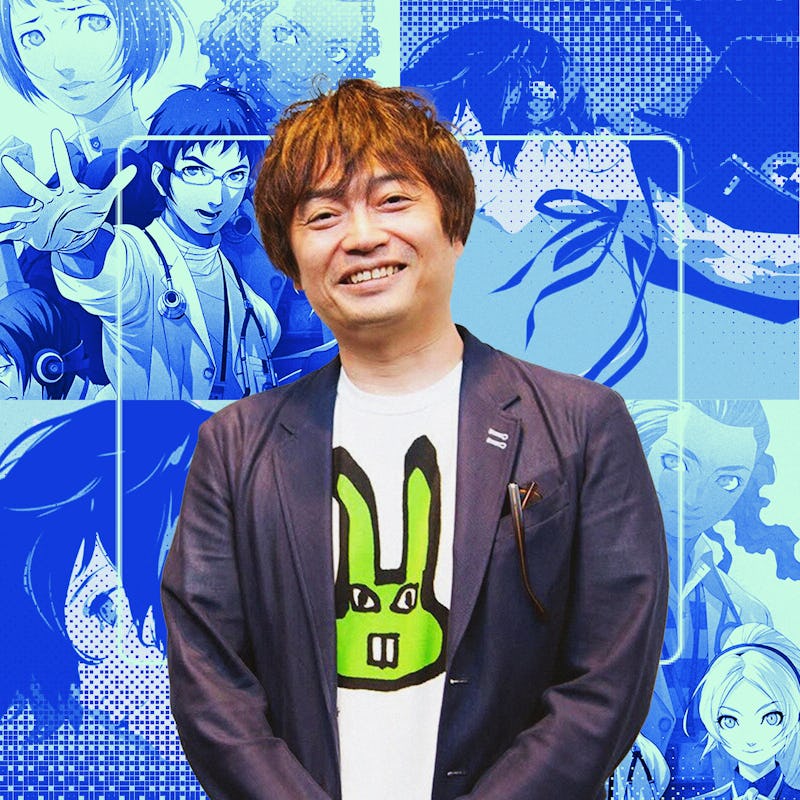

Katsura Hashino’s unbounded optimism for gaming.

So often, the creators we remember most fondly are the ones tinged with a hint of mystery — those that provide invaluable insights, but we never really feel like we can truly understand. As the world mourns the passing of David Lynch, it’s interesting to see how no two people have the same relationship with Lynch’s body of work. For some, he was an edgy auteur who shocked the world with 20-minute erotic scenes. For others, he was a mirror of the industry’s flawed view of film and television in how Twin Peaks eschewed the idea of linear storytelling.

In the realm of video games, a handful of creators fill that same niche — crafting perspective-shifting experiences that resonate deeply with a wide audience, but often for very different reasons. High among those creators is Katsura Hashino, a game director with more than three decades of experience crafting everything from paranormal high school dramas to sultry puzzle games about the complexities of relationships and monogamy. Hashino’s games have become known for delving into complex real-world themes, sporting striking art styles, and having layers of mystery and interpretation. But trying to pry open the door into Hashino’s mind oftentimes requires just as much interpretation as the game he makes.

“I feel it’s important for people to really just sit down and immerse themselves in a single story experience.”

For someone so shrouded in mystery, it’s surprising how earnest Hashino is, eager to answer every question I ask. He even seems ready to answer a question about his own personal trauma before realizing that I was actually asking about the cult-classic game series Trauma Center — which has a very different name in Japanese.

Hashino’s works have always been inventive subversions of genre tropes and ideas. Where all these ideas come from — Hashino is loath to put a point on it. He is, like his games, a mysterious character and an eloquent creator clearly eager to dive into the games he’s spent his life working on and playing. Hashino is a little hard to pin down for concrete answers — but like his work, it’s worth taking the time to try to read between the lines.

Running Out of Time

Persona’s time management lets you vicariously live out your high school days once again — even taking tests and exams.

You might not expect a reclusive, soft-spoken video game artist to love time management, but Hashino’s obsession is next level — front and center in his work. “Nowadays, there’s so much content and information around us, whether it’s in our PCs, our TVs, and our living rooms. There’s a word called ‘taipa’ in Japanese, which is a short form of time performance. How efficiently you can use your time.” Hashino says he thinks that’s why games like Persona have resonated so deeply with people — because ideas like struggling to manage time, before it slips away, are something that everyone deals with, no matter where or when they live.

In every Persona game, at least since Persona 3, you play a teenage protagonist attending high school before they’re pulled into some kind of paranormal world. The crux of the experiences revolves around scheduling out your time and making sure you make it through dungeons by the deadline you’re given. Players need to figure out how to juggle their busy school schedules with literally saving the world — and that’s proven to be an intoxicating formula. The mundanity of high school life is juxtaposed against often horrific supernatural events, and it’s up to the player to figure out how to parse everything.

Before he became known for Persona, Hashino worked on various other entries in the Shin Megami Tensei franchise — including Devil Summoner, Soul Hacker, and Nocturne.

Having to meticulously plan your schedule and prioritize which friends to hang out with has given Persona a unique flavor that genuinely represents the high school experience. “When we live our everyday lives, we’re doing our own time management. So having that sort of system brings out a reality in games that we, as people, can resonate with,” Hashino says.

“My philosophy, and what’s fun for me is that about 60 to 70 percent of the context should be something that is familiar and easy for people to grasp,” Hashino adds. “But on the flip side, if 30 to 40 percent of the game is an unknown realm, that grips and pulls them in — that sort of balance between known and unknown in one space.”

A Puzzling Way to Develop Games

The last Trauma Center game was Trauma Team on the Nintendo Wii in 2010. When asked if there’s any past games he’d like to remake, Hashino coyly responds with “I can’t really talk about that right now.”

Another reason Hashino’s games are so fascinatingly disorienting may stem from one very odd — some would say backward — way that he develops a game. In essence, he often starts with mechanics and finds a story later down the line.

Take Trauma Center, a game he had a hand in creating that would go on to span five entries across multiple systems. It’s a weird game with a story experience that is singular to the point of myopic: While it may be the lesser-known of Hashino’s work, interestingly, it may have been a key part in cementing his design philosophy. These largely story-based games like Persona didn’t necessarily start with narrative.

In 2005, the original Trauma Center used the touch screen on the Nintendo DS to perform surgery — like pulling glass out of a crash victim, stitching wounds, or using a laser to burn out tumors. As you clumsily fumble with the Nintendo DS’ tiny little stylus, you’re forced to race against the clock, using this highly specific instrument to save someone’s life in surgery, before it’s too late. That sense of urgency in the gameplay creates a link to the game’s narrative themes, heightening the soap-opera-style drama of its characters running one of the most bizarre emergency rooms you’ve ever seen.

“If there are certain elements that we’ve used in the past, and it matches what we want to convey, the themes, then we should not hesitate to include those.”

“When we’re talking about how I create games … we have an idea of the mechanics of the game in the center first. For Trauma Center, we have that surgery mechanic. For Catherine, it was the nightmare puzzle mechanics,” Hashino says. “We have those different mechanics mixed, then flesh that out by incorporating the story we want to tell. It’s not just about taking the characters or story and fleshing them up, but how we can elevate both the story and mechanics together. That formula helped me in the Persona games as well.”

Considering most of Hashino’s games are universally loved for characters and story, that might seem like a backward way of creating them. But it’s vitally important that every aspect of Hashino’s game works in concert, each piece feeding into those central themes, instead of splintering off.

Gaming as Metaphor

Metaphor cements Hashino’s idea of a journey through a fantasy world, and how entertainment like that can effect our hopes and motivations in the real world.

Other games have taken liberal inspiration from Persona’s time management, including the likes of Fire Emblem: Three Houses and Trails of Cold Steel. But the most obvious game inspired by Persona is Hashino’s latest creation, Metaphor. Even with an all-new cast of characters and unique storylines, the similarities are nearly endless. It uses the same style of turn-based combat, the same calendar and time management, but puts all that into the context of a rich fantasy world filled with prejudice and political upheaval. Again, it ties into that idea of drawing players in with familiarity — Metaphor intentionally uses those familiar systems before diverging into new territory. Using things like the calendar system was something decided early on.

“When we’re looking at Persona, and our time in high school, there’s a beginning and an end to that arc. And when we looked at Metaphor, we felt the same,” Hashino says. “We wanted to depict a journey with a beginning and end, and by giving the game that limitation, in terms of time, we felt that it would better convey the story and make people emotional.”

But with that being said, Hashino is quick to clarify that he’s not personally attached to the idea of time management — and just because it’s in Metaphor doesn’t mean it’ll be in the next game he works on, regardless of what it might be. That was actually one of the key lessons learned through Metaphor’s development, according to Hashino. He wants to carefully consider past systems or ideas that might be applicable to future games. “If there are certain elements that we’ve used in the past, and it matches what we want to convey, the themes, then we should not hesitate to include those.”

Elements of Hashino’s work seem to draw inspiration from the works of David Lynch, like the iconic Velvet Room from Persona bearing similarities to Blue Velvet.

It’s a far cry from the way a lot of modern games are made, having to constantly strive for the new instead of innovating on what’s come before. But it, perhaps, explains a part of what’s made Metaphor such an already impactful game. It’s a crystal clear example of Hashino and his team learning from the past and deliberately looking at that past work to figure out how to move forward. But even more than that, it’s the quintessential example of a video game meaningfully commenting on modern themes and topics.

In a lot of ways, Metaphor feels like the culmination of everything Hashino has done. Creating an enormous game like that is no small task — especially as the video game industry has been through a tumultuous few years filled with layoffs, studio closures, and more expectation than ever for a game to succeed. Metaphor itself was announced as Project Re:Fantasy in 2016, but it didn’t see a release until eight years later. But the human element has remained the most important. That’s true in the stories Hashino’s games tell and how they’re made.

“Metaphor was a very low-end game in terms of development, so it might be an outlier, but we weigh the size of the team, whether it’s 50 people, 100, or 300, see what ideas we have and what we can do with our resources in a certain amount of time,” Hashino says. “It really comes down to the team members that are working on a game. We’re human beings, so there’s a limit to how much focus and motivation we can keep in working on a single project.”

Every one of Hashino’s games strives to marry mechanics and story, to deliver a central core theme. In Catherine, it’s the nature of relationships and the creeping guilt and dread caused by infidelity.

The success of games like Persona and Metaphor has undoubtedly proven that there’s still hunger for expansive single-player games — and equally stylistic games that don’t endlessly strive for photorealism. The future is unknown for the video game industry, and advancements in tech, like AI and VR, inevitably mold it into something different. Not to mention different game concepts and styles, like live service. But despite all that, Hashino’s earnest spirit shines through — he still has hope that through the storm, video game creators can truly embrace the art form.

“Back in the day, we didn’t have computers; we had paintings on paper that were derived from people’s imagination. But where technology has evolved, computers and games have evolved as well. Compared to back when there was just painting, how it’s being exported is becoming much closer to and meshing with reality, more than ever before,” Hashino says. “We’ll see an evolution of how people play, and the technologies where people can interact with games. Something that’s closer to the reality [of the creator] than what it is now.”