The Original Far Cry Game Is Even Weirder Than You Remember

Far Cry opts mostly for pure chaos. And it mostly works.

The first-person shooter genre isn’t known for its storytelling. That’s not to say it can’t produce a classic video game narrative from time to time, but when a new FPS comes out, it’s primarily judged on the fluidity of its gameplay rather than whatever vague narrative is pushing its combatants through. However, there is one series that nearly always manages to call attention to whatever weird (and potentially misguided) plot that it’s attempting to pull off.

Far Cry was developed by Crytek, a German developer that, at the time of release, had yet to really prove itself on a massive scale. However, what the studio lacked in big achievements, it made up for in personality and a dogged will to be noticed by the industry. It’s calling card was initially a demo for a game called X-Isle, which put players on a tropical island filled with dinosaurs. Soon, X-Isle became a tie-in software with new NVIDIA cards and Crytek earned a partnership with Ubisoft. X-Isle eventually evolved into Far Cry, which officially hit stores on March 23, 2004.

Far Cry’s story is a not-so-subtle play on the classic Island of Dr. Moreau.

Far Cry doesn’t feature any dinosaurs (prehistoric creatures would have to wait until Far Cry: Primal in 2016), but it does feature mutant hybrids called “Trigens” that terrorize an island, courtesy of the mad scientist Dr. Krieger. It’s a play on the classic Island of Dr. Moreau scenario with an evil biologist seeking to improve mankind and other species by splicing their DNA. Krieger’s efforts in genetic experimentation aren’t very successful, however, and later in the game, it’s revealed that Krieger has a nuke on the island ready to blow if people show up and start questioning him. (It doesn’t show a lot of faith in the process if you have a “in case of emergency” atomic weapon in your stock.)

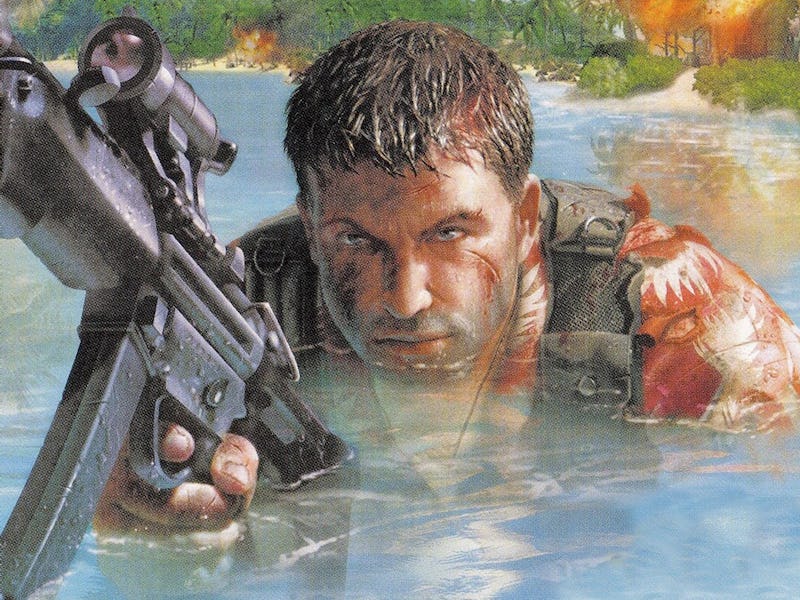

It’s an odd story, especially in comparison to the other first-person shooters that came out in the same week as Far Cry, like a Tom Clancy’s Splinter Cell sequel (black ops agent trying to stop some bio weapons) and a Counter Strike follow-up (a standard counterterrorism missions with different challenges.) And unlike Dr. Moreau, it does little to play with pathos or the innate tragedy of the mutants. Instead, Far Cry opts mostly for pure chaos, taking advantage of what, at the time, seemed like a sprawling world to explore and blast apart. The main character is a former soldier named Jack Carver who doesn’t have much of a personality outside of a mysterious past and a propensity for surviving outlandish things while continuing to mow down any creature and/or mercenary that happens to get in his way.

Later Far Cry games have you taking down religious zealots and fascist dictators. In the original, you fight these things.

This lack of worry for whatever ethical problems the narrative might encounter has become a staple for the franchise, one that becomes significantly less shocking when you play the “Yeah, they’re the results of horrific procedures and diabolical formulas, but they have guns too, so take ‘em out” original. Crytek would only develop the first Far Cry (Ubisoft took over the series after that), and the franchise it’s most known for today is Crysis, but the established approach to storytelling continues: Far Cry 2 had you diving into an African military conflict, Far Cry 5 had you taking on religious zealots, and Far Cry 6 sees you trying to topple a Caribbean dictatorship. (The games each tackle these thorny geopolitical topics with the subtlety of a Gorilla Trigen.)

All are approached in a way that prizes an exciting experience of movement and action over any attempt at a lesson or even a clean resolution. Mark Thompson, the level designer for Far Cry 3 once told Polygon that Far Cry “isn’t about a specific narrative or character.” Rather it’s defined by its lack of rules and “moral gray space.” The game is caught between a few violent ideologies, and the main character is just the one with the guns (and, in what will eventually become a regular feature for the series, an array of animals that are ready to attack enemies on your command).

Far Cry’s greatest strength is how it immerses you into its world.

In the case of the first Far Cry, any qualms with the story were severely outweighed by what many critics considered to be a near-perfect gaming experience. And it’s hard to not appreciate just how stellar Far Cry is at immersing you into its world. The AI of the enemies is fantastic and constantly leaves you guessing as you’re forced to reform your strategies. The environment, which was gorgeous at the time of release, is fun to traverse and offers many options for your various assaults. And considering how relatively threadbare the plot is here, it’s easy to forget about it altogether. When you’re being hunted by mutants that, if you’re not careful, will outhink you, the wider narrative becomes secondary.

Of course, as the games began to lean heavier toward more “realistic” stories and away from the bio-engineered monstrosities of the original, it became harder to ignore the fact that they rarely commit to any overall point. But if you’ve ever been surprised by a Far Cry game’s decisions, just know that they’ve been wildly swinging since the beginning. Can gameplay be so fun that you ignore any lingering doubts about its narrative? Far Cry’s answer: Eh, you’ll figure it out.