What 'Silent Hill 2' Gets Right About Mental Illness

15 years later, 'Silent Hill 2' is still doing horror right.

Horror has a tendency to misuse dark themes, which is a shame because that’s what the genre is best at embracing. Instead of detailing the true depths of mental illness or sexual abuse for example, horror tends to exploit them for monster encounters and cheap jump scares. In any piece of media that prioritizes short-term fear, discussions that showcase the writers’ understanding what these experiences are like and how they can affect people are rarely seen.

Silent Hill 2 attempts to do these tough topics justice, creating a place where trauma and self-doubt form the basis of a character’s fears. Despite being a 15-year-old game, the developers behind Silent Hill 2 understood that the most intricate kind of horror is the one most personal. The franchise’s greatest scares consist of the things that haunt us at night over the years rather than something that has a short-term effect, like a jump scare or a weird-looking monster.

Pyramid Head seen here with several mannequins.

This is a lesson that most modern video games still struggle with almost two decades after Silent Hill. The Evil Within — which utilizes an asylum as its primary location, but fails to consider the implications that kind of setting has on people with mental illnesses — is one such example. It’s a shooter that rewards you for killing those around you, demonizing those who can’t help themselves.The tragedies that humans can experience are dehumanized, used as cannon fodder for shock value and gore.

While The Evil Within and other games like it use tragedy as a plot device, Silent Hill 2 is a game about trauma itself: how people are affected by it, and how they cope. The game follows three characters who are drawn to the town of Silent Hill to deal with some horrific event that destroyed them. Since it was such an important aspect of the story, Team Silent, which worked on the title through the Konami game studio, put meticulous detail in trying to depict trauma fully. Instead of the player being tasked with hurting mental patients, the things that they have to kill are monsters that are the personification of their own individual mental illness.

There was a lot of attention put into these designs. The emphasis is put on physical form, location, and a particular monster’s grand reveal in order to further not just the scares, but also the narrative.

Not everything in the 'Silent Hill' games is symbolic, but a whole lot is.

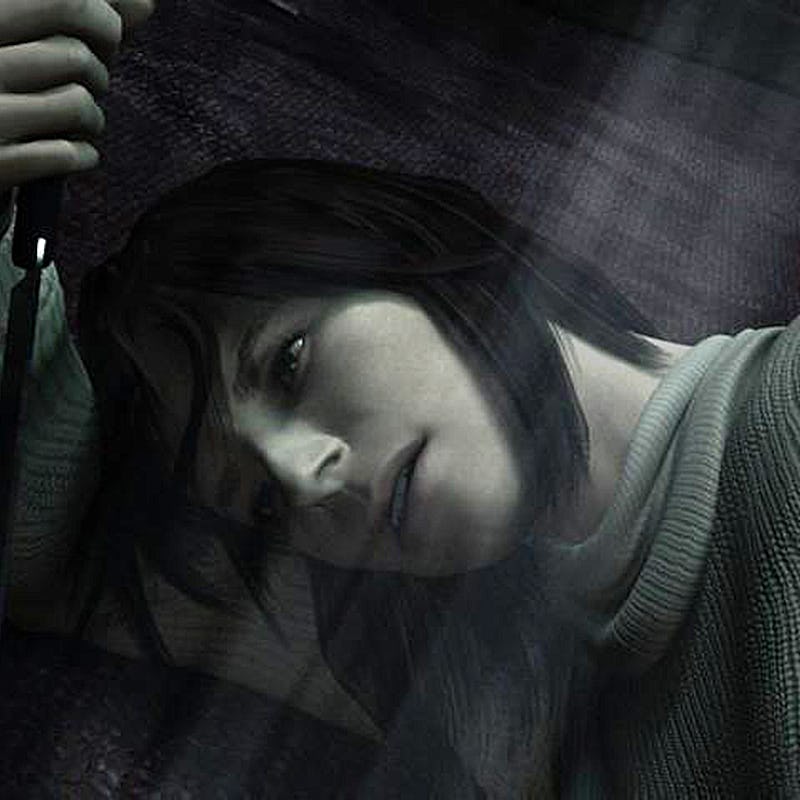

For example, Angela is a teenage girl who is carrying a large emotional burden. She’s tired, easily frazzled, and regresses into immaturity quickly when provoked by something stressful. While never explicitly stated, the story heavily implies that she’d been sexually abused by her father and that she killed him at some point before the events of Silent Hill 2 in retaliation.

While some of Angela’s backstory is told to us through dialogue, most of the storytelling comes in the form of one big clue: the Abstract Daddy, a monster that gets introduced late in the game. The Abstract Daddy is an outlier compared to every other monster in Silent Hill. It’s less humanoid than the others. The lying figures, the mannequins, Pyramid Head, and the nurses are bipedal and for the most part. The Abstract Daddy is more of a lumbering, pulsing tumor rather than something vaguely recognizable. It’s hard to make out what exactly it is at first, since it’s mostly just a large mass gyrating in strange waves.

The Abstract Daddies are out of place for another reason. Up to that point, every monster is attached to James Sunderland, the protagonist of the game who roams Silent Hill looking for his dead wife, Mary. Each monster is representative of something that’s haunting him and many can be tied to James’ sexual frustrations and guilt surrounding Mary’s death. James seeks companionship that he couldn’t get with Mary, who was dying of a terminal illness, and in his frustration Silent Hill conjures up the nurses, the mannequins, and Pyramid Head for him as punishment. The latter is the embodiment of masculine, sexual frustration. Pyramid Head’s first major scene is of him raping a mannequin monster, which doesnt necessarily disgust James besides the initial shock of seeing it. The nurses are sexualized with tight dresses and would be fanservice if they also weren’t so grotesque.

James meets Pyramid Head. Hello, there.

Players encounter all of these monsters before they get deep into Angela’s story and realize that the Abstract Daddy is actually hers. Then the player sees what it’s supposed to be: It’s a horizontal replication of somebody getting horribly violated.

Silent Hill 2 is a game that’s about sex, the different kinds of relationships we have with it, and the damage it can do to us. It’s a game steeped in symbolism where everything is done on purpose, and Angela’s story is the one thats most explicitly about sex. Her life is surrounded by a cloud of sexual trauma that defines by her relationships with the act, but it’s not the only one. James, our main character, is also haunted by his past experiences with sex, hence the appearance of the nurses, for example, which are a carnal manifestation of his urges while caring for his wife, Mary.

So if the Abstract Daddy isn’t his monster, then why does he get to fight them? That in itself is another piece of symbolism since James has been unwillingly tasked with carrying Angela’s burden. About an hour into the game, she gives him a knife she was threatening to kill herself with. As the player, you can’t make James use the knife for anything except to get the suicidal ending. In a way, she is passing her depression onto James and highlighting something in him that he didn’t want to face: his own desire to die. They reflected their grief in each other.

Angela deals with a sexual trauma that completely embedded itself into her being, making her timid and self-loathing. In the end, she isn’t able to overcome it, descending a fiery staircase to never be seen again. Her bleak story runs parallel to James’s. She can’t face her own demons and therefore doesn’t make it. James, on the other hand, could go either way.

There’s a whole trend of horror games that might not have taken inspiration directly Silent Hill 2 but capitalize on these types of intimate fears by personifying insecurities into something monstrous. Games by Porpentine, Kitty Horrorshow, and Frictional, along with titles such as Layers of Fear and Oxenfree take reality and turn it into something that reflects the grotesqueness of trauma on the human psyche. The connection that the players make between the experiences of the characters and their own fears only heightens the terror because it’s something all people understand. Dealing with trauma is universal, if not openly spoken about, experience.

Silent Hill is about facing that which wants to destroy us, that which we ourselves helped create. The game forces each player to confront that there’s no easy way to defeat their inner demons by trapping Angela in a place where she is forever stuck on the verge of violence. Exacting revenge only furthered Angela’s pain, but what else can she do in a world where she’s damned if she does, and damned if she doesn’t? Told through haunting character design, Silent Hill’s true horror is that you’re essentially killing pieces of yourself over and over again, and even that might not be enough.