In Sunlight, the Horrors Are All Too Real

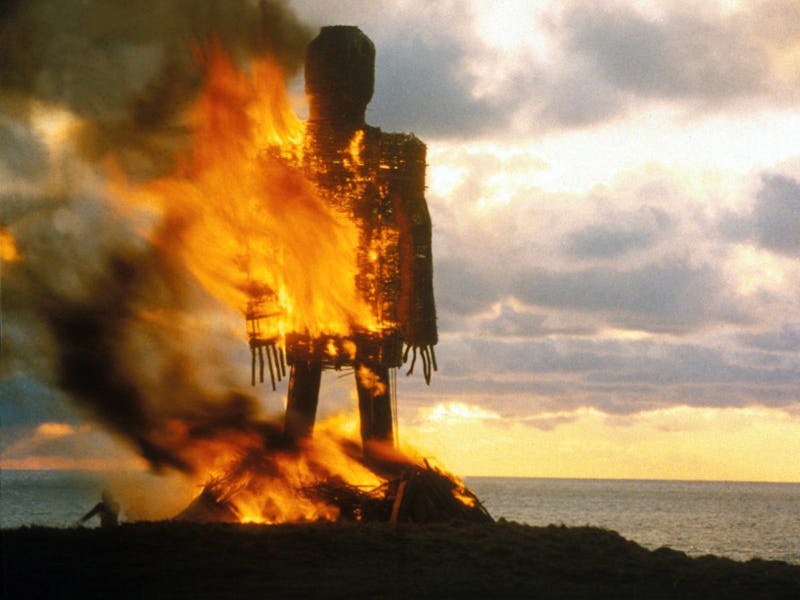

Fifty years ago, The Wicker Man delivered one of horror’s most effective lessons.

Danger thrives in the dark. Picture a lone alleyway at night or an attic with a burnt-out bulb. Horror has long relied on our fear of that which we can’t see, of what might be lurking in the shadows, which is what makes the absence of light such a natural incitement for dread. However, Robin Hardy’s The Wicker Man, set almost entirely during the daytime on the cheery, sun-dappled fictional Scottish island of Summerisle, concluded with the frightening revelation that evil could no more easily be detected under the harsh glare of the sun.

In the process, The Wicker Man helped popularize a new subgenre of horror.

Released a year earlier, Alfred Hitchcock’s The Birds (1973) weaponized not just the innocuous nature of daylight but the everyday, ordinary sight of a town's bird population, staging terrifying sunlit sequences, such as one in which a murder of crows did just that. Tobe Hooper’s The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974), released just a few months after The Wicker Man, contrasted the blazing sun against an overlooked insular community wreaking terror on the hapless outsiders who'd stumbled onto their land. Edgar Wright's Hot Fuzz (2007) is a more comedic riff on the premise of Hardy's film — an English cop being transplanted to an idyllic village only to uncover a sinister secret society — and echoes of The Wicker Man similarly reverberate in Gareth Evans’ The Apostle (2018), in which the protagonist travels to a Welsh island to rescue his missing sister from a cult. The film's DNA most noticeably runs through Ari Aster’s Midsommar (2019), with its scenes of pagan revelry and ritual sacrifice set under an endless Swedish summer sun. But 50 years on, The Wicker Man remains an distinctively unnerving masterwork.

The Wicker Man follows Sergeant Neil Howie (Edward Woodward), who travels to a remote island to investigate the disappearance of a 12-year-old local (Gerry Cowper). Early recurring shots of clear blue skies, azure waters, and flowers in full bloom set up Summerisle as an Edenic paradise; the cost of maintaining it revealed by the film's unnerving, hellish final scenes. The locals seem perfectly affable, solicitous in their offers of help, steadfast in their assurance that nothing is really wrong. But like the island, appearances are deceiving. There are layers of performance at work here, in contrast to Howie’s forthrightness.

The Wicker Man helped kickstart a new horror subgenre seen in films like Midsommar, The Apostle, and more.

At first, however, all that sunlight, reflective of the locals’ worship of the sun god Nuada, also becomes a visual shorthand for their unusual openness. There can’t possibly be anything dark or sinister in a place this bright, can there? With all this music, singing and dancing? It’s the sergeant’s conservative Christian rigidity that feels out of place, almost immediately clashing against the islanders’ free-spirited beliefs. As strange as their behaviour is — one woman breastfeeds at a cemetery — it’s Howie whose presence begins to feel intrusive and disruptive to the natural rhythms of their lives. The stuffiness of his uniform is in stark contrast to their comfort with public nudity.

The locals’ cooperation in the investigation extends to Howie being given free reign of the island — he listens in at the window to an ongoing class, is free to question who he wants and when he drops into Lord Summerisle’s (Christopher Lee) mansion at random one day, he’s told that he’s been expected. Yet every move he makes is precisely one the islanders have planned and accounted for, the choices made of his free will revealed to be mere manipulations by a community maneuvering him into doing their bidding.

Hardy doesn’t deploy jump scares or jolts, instead gradually intensifying the feeling that something is horribly wrong on Summerisle. The locals’ explanations for what might have happened to the missing girl get more convoluted as the investigation progresses, they grow evasive and begin trafficking in semantics. It becomes easy to assume, as Howie does, that their pagan beliefs have led them to justify committing an act of barbarity. And so, hellbent on uncovering what happened to the girl by now, we follow his misguided assumptions right into a trap.

Christopher Lee strikes a sinister figure in The Wicker Man.

The sergeant remains headstrong until the end, when the film’s puzzle finally clicks into place with a macabre flourish. He falls to pieces, his composure finally shattered. Hardy’s repeated shots of the sun during these scenes begin to feel like a cruel joke, its now-fading light a mocking symbol of Howie’s own diminishing prospects.

The Wicker Man’s opening scene, in which he spoke of Christ as a sacrificial lamb, has become an ominous portent for his own fate. Hardy never needed to rely on the cover of darkness to pull off his film’s ultimate, sickening twist. In getting the audience to believe that, like his protagonist, they could clearly see where this was going, then pulling the rug right out from beneath their feet, he delivered one of horror’s most effective lessons — too much sunlight can be blinding.