The Boy and the Heron Rejects the Most Boring Studio Ghibli Stereotype

The Boy and the Heron is Miyazaki’s greatest, and most hopeful, apocalypse movie.

The opening minutes of Future Boy Conan, Hayao Miyazaki’s’ classic but seldom-seen 1978 directorial debut, is a prophetic vision of our eventual self-destruction. Sieged by a future war and post-nuclear weapons of mass destruction, humanity has doomed itself; cyberpunk mega-cities crumble, populations are wiped away, the climate withers, and the waters rise. In the decades since Future Boy Conan, Miyazaki has developed a reputation for warm-blanket whimsy that can nurture the soul like the best bowls of noodle soup. But from the beginning of his career, he has always wrestled with the dark and difficult emotions that smolder inside us, and the deadly consequences they can unleash.

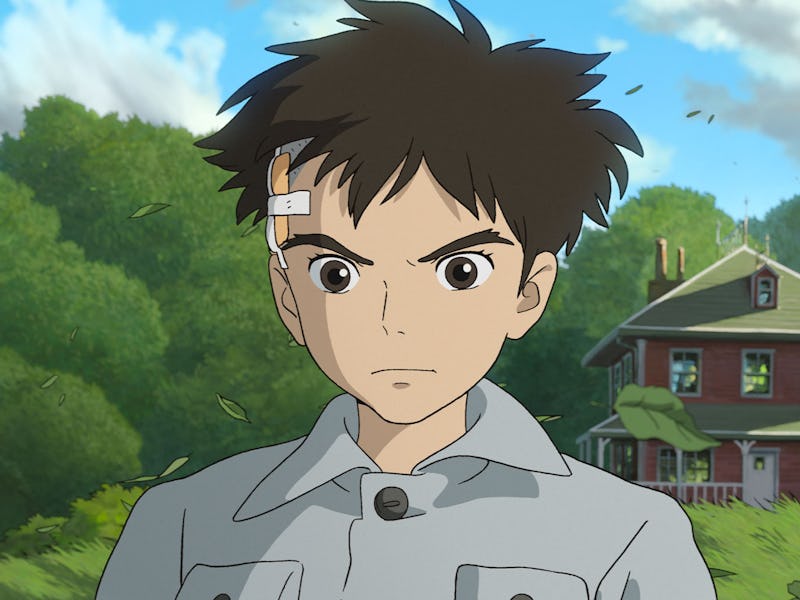

It seems inevitable, then, that Miyazaki’s latest film, the mournful, rhapsodic, and heart-shattering The Boy and the Heron, follows Miyazaki’s darkest protagonist yet, a boy named Mahito, whose tormented soul turns to malice in the flames of World War II. And in focusing on such an uncharacteristically grim hero, Miyazaki also rejects the “Cozy Ghibli” aesthetic his films have too often been reduced to, with a startling source for the character’s inspiration: Miyazaki himself.

Hayao Miyazaki’s latest self-insert is also the most unflattering.

Unlike any previous Miyazaki, The Boy and the Heron is a semi-autobiographical bildungsroman that features details of his own life — a mother absent during a painful youth, a father consumed with airplane part manufacture, the impact of witnessing the horrors of war at a young age — that then travels into a chaotic netherworld that might as well be his subconscious. With an entropic plot that obeys no logic but its own, The Boy and the Heron seems to drip like magma from the most volcanic corners of Miyazaki’s mind and, through Mahito, reckons with how to confront, and ultimately embrace, the messiness of life in all its beauty and horror.

Miyazaki’s Darkest Protagonist

Mahito loses his mother in the fires that take Tokyo.

Mahito is a 12-year-old boy mourning the sudden loss of his mother, Hisako, in a fire-bombed hospital fire in 1943 Tokyo, and one year later, is forcibly relocated to the country estate of his new stepmother, Natsuko. His internalized angst clashes with the sylvan beauty of his surroundings, and his workaholic father offers little comfort. Soon after, a mystical gray heron aggressively beckons Mahito to enter a mysterious tower on the grounds, an unlikely gateway to a stygian dreamworld that carries the promise of rescuing his mother from death. This turns out to be both a truth and a lie; a much younger version of Hisako dwells there as the fire-witch Himi, and as she joins Mahito on his quest, this mother-son bond that recalls Céline Sciamma’s Petite Mamon is key to pushing him toward the light.

After taking the heron’s bait, partly to save his mother and the now-vanished Natsuko, Mahito enters this protean underworld where Miyazaki’s lifelong passions and deepest fears are made real. We see echoes of that iconic Ghibli look; there are stunning panoramas of vast seas and purple-orange skies, with grassland cottages giving way to adorable pillowy creatures called warawara that ascend to the heavens for rebirth. Yet, we see also Miyazaki’s decades-long preoccupation with mortality and the specter of war, visualized through vast galleon fleets that ferry the dead through the horizon, a mortally wounded pelican grieves the cruelty of natural order, and an army of fascistic, human-eating parakeets threatening to usurp power, as though somewhere in Miyazaki’s fearful head there’s always an army stoking another war.

Natsuko and her army of maids.

Mahito learns this was all the scheme of his long-vanished granduncle, who reigns as the godly steward of this surreal, dazzling world. With his kingdom nearing its end, the granduncle, as much a proxy for Miyazaki as Mahito, sent the heron — actually a weird little guy who pulls down the bird’s head like a skin suit — to coax Mahito to him as his successor. Out of caution for the malice growing inside him, Mahito refuses, and with unwanted help from the tyrannical Parakeet King, the granduncle’s dreamy world crumbles.

Compared to Spirited Away’s Chihiro or Howl’s Moving Castle’s Sophie, Mahito is unusually troubled for a main character from Miyazaki, subverting what we think of as the archetypical Ghibli lead. His protagonists are never simple but are almost always kind, as eager to help a stranger as they are to take flight. In contrast, Mahtio, in fits of grief, has a prickly froideur that alienates him from those who would care for him, including the warm affections of his new stepmother. He even tells off the elderly maids, bluntly stating their rice is disgusting. At first, he is Miyazaki’s most difficult protagonist to like, inviting sympathy for his situation more than his personality, which softens as the film goes on.

Mahito is deprived of the classic lovable Studio Ghibli sidekick like Calcifer in Howl’s Moving Castle.

For more than an hour, Mahito is painfully alone, with Miyazaki withholding the equivalent of the classic Ghibli sidekick, a Haku or Calcifer, to quickly soothe the boy’s intense mourning. In addition to Himi, the closest is the titular heron, who eventually bonds with (and rescues) Mahito, but only after warning “we’re not friends or allies, kid.” Of all Miyazaki heroes, he might be closest to the aggrieved melancholy of ace pilot Porco Rosso, but taken to jolting extremes as Mahito’s pain metastasizes into helpless rage.

In The Boy and the Heron’s most upsetting scene, we witness Mahito’s growing fury, malice as he names it, in the most physically gruesome terms. Mahito gets into an after-school fight and rather than go straight home, he picks up a rock, crashes it into his skull, and unleashes the biggest geyser of blood seen in a Miyazaki movie since Ashitaka made samurai heads fly in Princess Mononoke. It’s a moment of silent grief turning toxic, a boy whose childhood innocence was damaged in the unkind flux of life.

Fascinatingly, we can see this scene’s thematic mirror in The Wind Rises. The main character, Jiro, stops a bully picking on a younger child, only for Jiro to then flip the bully over his head. Immediately, Jiro’s mother cautions him: “Fighting is never justified!” she says, life-affirming pacifist wisdom that means most when given by a mother. It’s as succinct a thesis to Miyazaki’s philosophical outlook as in any of his films, while also showing the price of not having a mother to guide you into a happier future.

That profound yearning for maternal care hangs over every minute of The Boy and the Heron, and in that chronic solitude and despondency, Mahito chooses what no Miyazaki protagonist before ever has: murder. He becomes obsessed not only to confront the baiting heron, but seemingly, to kill him. That his chosen weapon is a homemade bow and arrow only reinforces the tragedy of Mahito’s lost innocence: the ideal plaything of a near-teen is given the life-and-death stakes only a child who lived through war could know.

When Mahito and the heron are forced to become allies, neither of them are happy about it.

The first half of The Boy and the Heron climaxes when Mahito finally faces his enemy and nearly kills him with the first shot, missing his head by inches and threatening to loose a second lethal arrow unless he’s told the location of his family. This is among the most deceptively horrific scenes in all of Ghibli; it is the closest any Ghibli hero, much less one that’s 12 years old, has come to committing an act of torture.

In fact, for much of The Boy and the Heron, Mahito’s malevolent aura reveals he could have easily been one of Miyazaki’s sympathetic villains rather than the film’s hero. Miyazaki has always broken down simplistic binaries between good and evil, characterizing his strongest antagonists as relatably human even as they cause great harm. Princess Mononoke’s Lady Eboshi might be his greatest, who houses the sick and provides safe work for women as she ravages the nearby forest and battles its gods. It’s not a stretch that Mahito’s trauma and grief could have served as the humanizing backstory for a new villain’s escalating cruelty, all the more bracingly revealing when you recall Mahito is meant to be an autobiographical proxy for one of our greatest living filmmakers.

Looking to the Apocalypse

Given the chance to make his own world, Mahito rejects it.

Ghibli has always been more adult than its pop reputation would suggest, balancing sophisticated ethics with studied condemnations of war and the accumulation of power, depictions of industrialized capitalism, and the inherently oppositional relationship between man and nature; for humankind to thrive, nature must wither, Miyazaki’s work suggests. Castle in the Sky is slyly pro-union, and more than half of his movies feature an end-of-days scenario.

This all comes from a creator who is, infamously, a sad icon. The internet is populated by clips of Miyazaki strolling around roofs, offices, and backyards puffing a cigarette and waxing how depressing and hopeless it all is. Speaking to The New Yorker in 2006, he even said: “I’d like to see Manhattan underwater. I’d like to see when the human population plummets and there are no more high-rises, because nobody’s buying them. I’m excited about that. Money and desire — all that is going to collapse, and wild green grasses are going to take over.”

In that light, Miyazaki’s “Cozy Ghibli” aesthetic seems as much a balm to his casual nihilism as it’s a comfort to his family of characters, and The Boy and the Heron brings that decades-long conflict between dark and light full circle through a rare character who needs to heal as much as Miyazaki does.

Through Mahito’s journey with a younger version of his mother, Miyazaki finds catharsis with his own childhood.

It’s as though in Miyazaki’s head the gamut of reality, emotion, and dreams bleed together as one, a whirlwind of storytelling, theme, and abstract rules that exist only to create an odyssey for Mahito — and Miyazaki himself — to treat their deep wounds. The Boy and the Heron ends not with trying to fight death or erase man’s inherent malice like a baptismal purging of sin, but of accepting it as a resolute part of being human, and having the strength to seek out, and accept, the support of those who love you. So, Mahito may channel his love from one mother to another, finding the family belongings he so desperately needs.

Miyazaki can imagine reuniting with loved ones long gone, where through the avatar of Mahito he can again hug his long-deceased mother, who in real life died when Miyazaki was 39. He can see the next generation born above through the warawara, and he can nurture and feed the dead. And Miyazaki’s final apocalypse, the granduncle’s collapsing world, isn’t one of global annihilation, but letting a magnificent kingdom fall away so the next generation may create their own.