With One Special Edition Release, James Cameron Changed Movies Forever

Here’s how The Abyss special edition version inadvertently created the director’s cut.

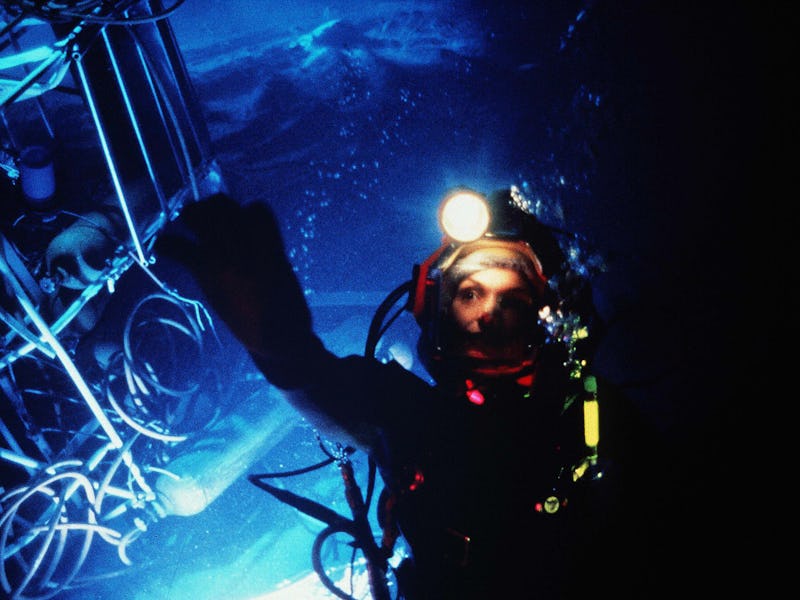

It was 35 years ago this week that writer/director James Cameron released The Abyss. Hot off the success of Aliens in 1986, Cameron delivered an original science fiction action thriller about the crew of a deep-sea oil drilling platform forced to help a SEAL team recover a sunken nuclear sub from the deepest depths of the Caribbean before the Russians can find it first. Oh yeah — there’s something else down there as well, and it ain’t a school of fish unless they’re purple and glowing.

The Abyss was not only Cameron’s most personal film to date (the estranged couple at its center mirrored Cameron’s own marital strife at the time), but his most expensive and difficult to make up to that point, due mainly to the extensive underwater filming and breakthrough use of CG for some of the visual effects. Upon its release, The Abyss was met with general approval from the critics but indifference from audiences. The movie logged only $90 million worldwide, including $55 million domestically — enough for it to be considered the future Avatar director’s first (and, financially speaking, only) flop.

One problem critics and audiences seemed to have with The Abyss was that it played as a largely exciting, suspenseful thriller with a layer of undercooked sci-fi underneath. It’s clear early on that there are aliens hiding at the bottom of the Cayman Trough. But their arrival on the surface at the end — saving the platform, its crew, and hero Bud Brigman (Ed Harris) in the process — suggests they’re simply moved enough by Bud’s love for his wife Lindsey (Mary Elizabeth Mastrantonio) and willingness to sacrifice himself to save her that they decide they want to hang out with us.

In fact, the 140-minute film had actually been notably longer — nearly three hours — in Cameron’s first cut before Fox insisted he deliver a shorter version of the film so theaters could schedule one more screening a day. Cameron obliged, but ended up slicing out both the deeper reason for the aliens revealing themselves as well as the context for it.

Cameron removed scenes that heightened the tensions between the U.S. and the Soviet Union to the point of possible nuclear conflict — which is what brings the aliens out of hiding. Showing Bud (via images lifted from TV broadcasts) that they understand all too well our capability for self-destruction, the aliens threaten to simply wash human civilization away by deploying gigantic tidal waves around the world. It’s only Bud’s selflessness that convinces them that there may be hope for us yet.

The original theatrical version removed the geopolitical context that lends The Abyss such weight.

So-called “director’s cuts,” along with “special” or “extended” editions of films, have been around since the early 1970s at least. In many cases they merely include footage the director had to remove the first time around for length, pacing, to secure a certain rating, or other reasons. The 1993 restoration of the deleted footage to The Abyss, however, was perhaps the first prominent example of a new version of the movie changing the meaning of the film itself.

Fans debate which version they prefer to this day, but the Special Edition of The Abyss is the fuller, more complete story Cameron wanted to tell, with better development of its characters and themes, as well as a more satisfying, resonant ending. And in the years since its release, bolstered by online fan discussions, film history archaeology, and the home video market (until it imploded), a literal parade of films has since been re-released or restored in versions significantly altered from the original cuts.

The director’s cut gives the aliens more motivation than simply “love.”

We’re not talking about just adding more scenes to The Lord of the Rings — the extended versions of those films are a richer experience in many ways, but don’t change the fabric of the trilogy itself. We’re talking about different cuts that have transformed a film’s message and meaning, like the more spiritually-oriented “Version You’ve Never Seen” of The Exorcist, or the far more brutal, nihilistic original version of Conquest of the Planet of the Apes.

There’s also Ridley Scott’s “Final Cut” of Blade Runner, which sharpens the film’s existential questions about humanity by making it clear (to most folks, anyway) that Harrison Ford’s Deckard is a replicant. Scott also rescued his 2005 Crusades epic, Kingdom of Heaven, from cinematic obscurity by restoring some 45 minutes to the film, changing it from a middling action period piece into a true historical epic. In the superhero genre, Richard Donner’s cut of Superman II made vast changes to the theatrical version, giving it more gravitas and clarity, while, whatever you may think of Zack Snyder’s Justice League, the four-hour behemoth is a vastly different and improved animal from the truncated 2017 theatrical cut.

The list goes on (and will no doubt continue to grow in years to come), but ironically, one name is missing from it these days: James Cameron. His movies now come out in whatever form and length pleases him. But thanks at least in part to The Abyss, other filmmakers can enjoy the same opportunity.