Inside the Wild, True, Hot Mess That Was 1993’s Super Mario Bros.

And the deleted ending that makes the entire movie make sense.

In 1993, no one had ever made a live-action movie based on a video game. In the spring of that year, Super Mario Bros. demonstrated why.

Stories about the film are the stuff of Hollywood legend. Though Super Mario Bros. had the blessing of Nintendo, which had created the world of Mario and his brother Luigi in 1985, things went from bad to worse on a production that seemed cursed the moment the first word of the first draft was written. By the time the film was released, there was no hope. “We lost the actors,” says co-director Rocky Morton, who calls the experience “humiliating” and “deeply hurtful.”

“They kind of revolted against it,” he adds. “Nobody was happy about it.”

The film, which deliberately bore absolutely no resemblance to the video game, was set between parallel New Yorks in a world in which the dinosaurs never went extinct but evolved undetected, side by side with humans. The villain — a human version of Bowser called King Koopa — is played by Dennis Hopper, who must retrieve a meteorite fragment from a woman called Daisy (Samantha Mathis) in order to join the two parallel realities together and take over the world. It was a confusing, constantly shifting story that drove some of its central players to the brink of madness.

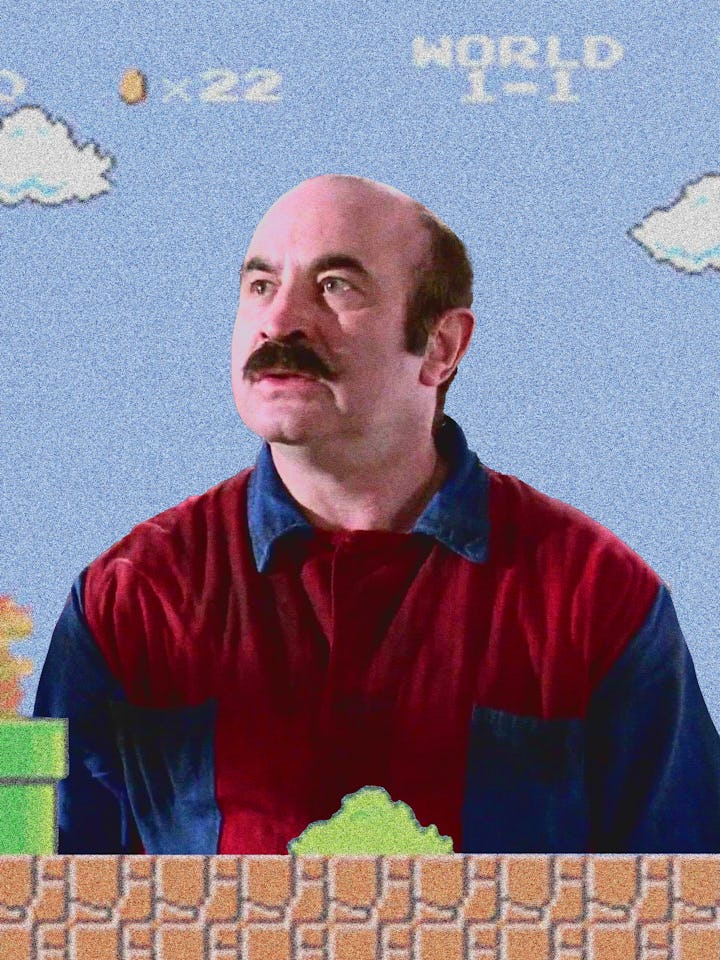

The actors who had come aboard, including John Leguizamo as Luigi and Fiona Shaw as villain Lena, had justified their decision to star in the film because the script had been so appealing. When this script was hastily rewritten, and the screenplay became an incomprehensible patchwork, there was something close to a mutiny: suddenly a film based on a video game didn’t seem like such a good idea. Fourteen years after the film came out, Bob Hoskins, who played Mario, said, “The worst thing I ever did? Super Mario Bros. It was a fuckin’ nightmare.”

But was the film unfairly lambasted? It certainly has a keen (if ironic) appreciation in 2023, perhaps because of its distinctive aesthetic and in-camera effects. This year sees another attempt to dramatize the game, this time in CGI with Chris Pratt voicing the mustachioed plumber. Will The Super Mario Bros. Movie succeed where Super Mario Bros. faltered?

Thirty years after the original was released, Inverse speaks to eight of the people involved in the doomed production to find out exactly what happened.

“This is a great concept”

Dinohattan in Super Mario Bros.

Roland Joffé (producer): I thought there was something inside that story that could be very interesting. I went and negotiated on my own with Nintendo. I think it took me a week staying in a ryokan in Japan and going every day with different kinds of tea, which I presented to the secretary of the then-owner of Nintendo. He said to me, “Lots of big studios want to do this. Why would I be interested in one person?” And I said, “Because you’ll get something original out of us.” He laughed and the next thing I knew we got the franchise.

Rocky Morton (co-director): One day this script came in and it said “Super Mario Bros” on the front. I rushed in and said to Annabel [Jankel, co-director and wife], “This is it. This is our next film.”

Fiona Shaw (Lena): Roland and Jake [Eberts, co-producer] were very invested in the film because they bought the title for $1 million a word.

Roland Joffé: I always thought Rocky and Annabel were extremely talented. I loved Max Headroom; it was adventurous and advanced and I knew we would get something very interesting out of them.

Rocky Morton: I call up the agent and I say, “This is a great concept” — it had never been done before — “but I didn’t like the script [by Barry Morrow].” She said, “Why don’t you think of an idea and pitch it to the producers?” It was based on this idea that 65 million years ago a meteorite hit the Earth and shifted the dimensions on the planet. They thought it was better than the original Morrow script.

Directors Rocky Morton and Annabel Jankel on the set of D.O.A in 1988

Dick Clement (co-writer of early screenplay): We were very surprised when we were asked to do the gig because we’d never seen Super Mario Bros. We knew nothing about it whatsoever. We’re not fans of video games.

Rocky Morton: I wanted the main story to be a love story between two brothers. Mario was forced to raise Luigi because their parents had died and he became Luigi’s surrogate mother, and Luigi resented having a mother figure and not a big brother figure. Mario resented Luigi for holding him back from his life’s ambition of being an artist. The story was this incredible, long adventure that they go on, and they learn to love each other through this extraordinary adventure.

“It was utterly brilliant. Fantastic. Emotional. Beautiful script.”

Dick Clement: The stuff we had written we always liked to keep grounded in reality. This was not.

Rocky Morton: It was utterly brilliant. Fantastic. Emotional. Beautiful script.

Roland Joffé: When I read that screenplay, I felt that it was lacking some kind of magical side. I think it’s the idea of imagining a completely different world — a world in which two plumbers are invested with magical abilities and in a world where the dinosaurs had not been wiped out. The dinosaurs had evolved.

Dick Clement: Suddenly we got this torpedo in the engine room: Nintendo got involved. They took exception to some of the things that were in our script, and, much to the chagrin of the directors, they removed us and moved on. Roland Joffé, I have to say, was not particularly supportive. Having done the sort of stuff he’d done, I think he thought he was slumming it slightly.

Bob Hoskins and John Leguizamo as Mario and Luigi.

Rocky Morton: As we were going into the film, we realized that it was costing more money than they actually had — because it was an independent film at that point. The only way to get some money would be to sell to a studio. Nobody in Hollywood was interested. Annabel and I had just made a film called DOA with Jeffrey Katzenberg at Disney. And he’s the only one in Hollywood that picked up. But the proviso that came with the money was that this had to appeal to little kids. Then we were really close to principal photography and it was given to Ed Solomon to rewrite it down to a lower age group.

Ed Solomon (worked on rewrite): I remember there was a lot of fear because they didn’t have a distributor. So Ryan Rowe and I did this two-week rewrite. And after the two weeks, Disney came on to distribute it.

“The script had been torn to shreds and cut and pasted into all these other things.”

Rocky Morton: The script was just so different. I’d storyboarded the entire film. These storyboards were 8 feet high and 20 feet long. I can remember piling them all up in the parking lot and setting fire to them all because they were detrimental to the film.

Ed Solomon: They asked if I could do a little polish. I agreed. Then a month or two later, I got another call. They basically said, “It’s chaos on set. Can you come down and just help with a few scenes?”

The crew of Super Mario Bros. pose for a photo.

Rocky Morton: The producers forbade me to speak to the writer, giving me the excuse that “He’s too busy.” I called him up anyway and said, “Look, Ed, I’m down here building all these sets and I’ve created all these monsters and creatures and things” to try and make sure they were included in the new script. The producers found out I’d spoken to him and they went absolutely ballistic at me.

Ed Solomon: I walked down there and it was absolute chaos. The script I had written with Ryan had been torn to shreds and cut and pasted into all these other things. Rocky was not even remotely happy that I was there. He did not like the work I had done.

Rocky Morton: We were being threatened. If we caused too much of a fuss we would supposedly get fired. We had this conversation: “This is a debacle. What should we do? Should we walk away from this thing or should we try to soldier on?” I think we made the wrong decision but we decided to go forward. We thought that we could do some rewrites and improvisation along the way, and make the film we wanted to make, which now I realize is such a naïve way of thinking.

“There was just a giant sense of What the f*ck is going on?”

Ed Solomon: Annabel was really nice and very grateful to have help and was really a nice person. I remember Rocky only being mad at me, hating everything I did, and not being open to any suggestions I was having.

Rocky Morton: As directors, we had to pretend we loved the new script. Nobody was happy about it. Sometimes, whole sets didn’t even make sense.

Ed Solomon: I remember there was a tremendous amount of confusion on the set — like “We don’t know what we’re shooting. We don’t know what we’re designing. We don’t know what’s in the script and not in the script.” There was just a giant sense of “What the fuck is going on?”

Roland Joffé: There was a tremendous amount of creative conflict. I don’t think it was actually anything to do with screenplays. Rocky and Annabel were quite new at the job and it was a very large morsel for them to bite off. I don’t think they liked me very much, but directors don’t have to like their producer. My job wasn’t to be lovable, it was to try to keep everything on the road.

“We made the whole thing up”

A Goomba in Super Mario Bros.

Fiona Shaw: The genius of the film was that the design was fantastic. It was shot in this big huge cement factory. Probably illegal now. It meant you could crash things and build a city.

David L. Snyder (production designer): Because the steel concrete framework was there, we would do basically what they do in England: build scaffolding and hang the sets on it. One by one, we started plugging the sets into the existing thing.

Simon Murton (assistant art director): We were slightly worried about the air pollution.

“We could fry an egg on the floor.”

Beth A. Rubino (set decorator): It was very oppressive. It was hot and enormous and crazily ambitious. It was 100 degrees. I have this incredible memory of us on one of the upper floors in an excruciatingly hot situation. They had fire bars going. I swear, I had one of my crew members check we could fry an egg on the floor.

David L. Snyder: Visually, I don’t believe there are any elements of the video game that exist in the final sets because it wasn’t practical. We made the whole thing up.

Beth A. Rubino: We did talk about the video game, but this was a polarity of two worlds — the dino world and the Mario world. It’s dark, it’s sexy, it’s gritty, there’s something taboo about it.

Concept art for the movie.

Beth A. Rubino: The fungus was a whole other character in itself. It was an organic bit of latex. It’s like doing cobwebs: it either looks fabulous or it looks like Halloween.

Simon Murton: That was a nightmare because we were using latex and we had a whole team of people on big sheets of glass laying out latex and letting it dry and then rubbing it to create holes and making it look nasty. Then, someone discovered this fishing lure rubber that you could heat up and create shapes and everything — the stink was awful. We had to layer it up all over sets and vehicles and we never had enough. We had people working around the clock on this horrible chemical heat thing. That was a little bit inhumane. I don’t know what it really added to the production. I got all the crap jobs on this one.

David L. Snyder: It was just designed day by day, day by day. The film looks the way it does almost by accident. It’s not a great movie but it looks great.

Snakes and (hot?) coffee

Fiona Shaw and Dennis Hopper as “Lena” and Bowser.

Roland Joffé: It was a dangerous shoot. There were an enormous number of stunts and it was a tough environment.

Fiona Shaw: The real stunts were done by Hell’s Angels and the guys that could drive those futuristic cars.

Fiona Shaw: The animal people said, “Would you mind taking the snake [that Lena holds in scenes] home?” I was asked to keep the snake so it would get used to me. It was a corn snake. The idea was that I would take the snake home, have it on my vast bed the size of a football pitch, and it would sleep down there in a bag. It began to cough up these fur balls. It was quite disgusting. I don’t think it got to know me very well because it did bite me. The whole thing was slightly Wild West-ish, I have to say. Think of the snake — the snake shouldn’t have to go and spend the night in an actor’s house.

“We got an old taxi and we crushed in the bumper and also the grill, and then we inserted a skeleton into it so that it looked like it’s been hit at 120mph but still in one piece and still holding a briefcase, then painted yellow.”

Roland Joffé: I certainly don’t remember Rocky pouring coffee on an extra’s head. If it had happened it sounds like there’d have been a major incident.

Rocky Morton: That comes from John Leguizamo’s memoir. This is what happened. The extras in Dino-York, the fantasy dinosaur world, wore a lot of synthetic leather outfits because it was like a scaly kind of skin. The suits, when they put them on, were really really shiny, and it was really distracting for the scene. I said to the wardrobe people, “You’ve got to dirty these suits down and make them matte so they don’t catch the light.” I called one of the extras over, and I picked up some dirt on the ground and I poured it onto his shoulder and I tried to rub it into the latex outfit. But it just kept falling off because it was so shiny. So then I picked up my coffee — which was not hot — and I got some dirt and I put it on his shoulder and I poured the coffee and started rubbing it in. He kinda overreacted. John Leguizamo saw this and interpreted it as me throwing my coffee — like I’m sitting at the monitor, this superstar director, “Hey motherfucker,” throwing hot coffee over everything.

Fiona Shaw: We were given leaning boards. So in between takes or when they’re changing a scene, the actor has to just stand and lean back. You can’t lie down, you can’t bend your tummy. You just had to stand like that. It was very uncomfortable.

On-set strife (and Shakespeare)

Bowser with his Goomba henchmen.

Roland Joffé: This is a story of a hothouse of creativity, emotion, danger, imagination, all at white-hot heat, and it would be odd to expect that to not have its own extraordinary set of tensions. It was like going to war.

Fiona Shaw: Bob used to get special whiskey sent from England — single malts — and we would drink those copiously in his caravan.

“Bob was Macbeth and I was Lady Macbeth.”

Roland Joffé: He was irritated but I don’t think he was driven insane. I can see Bob thinking it was the worst experience of his life, but in truth, if you’d asked those plumbers they would have said exactly the same thing. He, very much like these plumbers, had found himself in a completely different universe with people who were intensely visual and weren’t really interested in long discussions about motivation but were interested in, “Are you bigger or smaller than a goomba?” and, “Could you jump off a 25-foot-high cliff and bounce back up again?”

Rocky Morton: We lost the actors. They kind of revolted against it.

David L Snyder: Every Sunday, the cast was so unhappy with the turn of the film they would go to Wrightsville Beach and do Shakespeare — a cleansing.

Fiona Shaw: Bob was Macbeth and I was Lady Macbeth. We’d have takeout on the table. I had this vast gothic table. People were very excited about it, just to get themselves away from the set.

“He was irritated but I don’t think he was driven insane.”

Fiona Shaw: It’s not a good idea for a husband and wife team to direct. It means there’s always a contradiction of the direction. Dennis Hopper found that very hard and I think behaved often very impolitely because of it.

Rocky Morton: He was playing a lot of golf. He really didn’t want to show up. He just wanted to come in, do his job, and leave.

Fiona Shaw: I do remember Dennis coming into the makeup trailer every day and looking up everybody’s skirts. He was a really badly behaved person.

Rocky Morton: He did [an interview for] an article for the LA Times where he just laid into us; unbelievable vitriol against us. The fact that it was all our fault and [he] blamed us for everything. CAA dropped us after that article came out. We got fired immediately.

“The sorrow of this film”

From left to right: Mario creator Shigeru Miyamoto, David L. Snyder, Bob Hoskins, and Nintendo legend Takashi Tezuka at the world premiere of Super Mario Bros.

Rocky Morton: There’s a scene missing, that the producers cut out. The scene was right at the very very end when the Mario brothers were back in Brooklyn. And there’s a knock-knock-knock on the door, and it’s two executives from Japan from Nintendo. They’ve come to buy this story — the life story of the Mario brothers — because they want to use it in this video game they’re producing. They write down the story, dictated to them by Mario and Luigi, and it all gets lost in translation. And that was the crucial scene of the movie because it made sense of the entire movie and why the movie was so different to the video game, because it got lost in translation by Nintendo. We shot it and everything, but they cut it out.

Fiona Shaw: Maybe the sorrow of this film, if there is a sorrow, is that the potential of it was huge.

Roland Joffé: What came out was odd. We didn’t set out to do what we should have done. We set out to see if we could make something different. And we did make something different that some people really connect to.

“The film was well ahead of its time, actually.”

Rocky Morton: I think the criticism was unjust. Back then, most film critics were in their 40s and they didn’t get video games.

Roland Joffé: I think the film was well ahead of its time, actually.

Rocky Morton: As directors, we are directly responsible. I take complete responsibility for the entire film, with its faults and everything. I could have walked away from it. I tried to help everyone because it was our second film and we were very naïve. The experience was so humiliating and so deeply hurtful that it really destroyed our creative energy together. Hollywood missed out.

Fiona Shaw: I think it’s found a new audience who are not judging it according to the values of that time.

Rocky Morton: There was a 30th-anniversary screening the other night in Hollywood, at Quentin Tarantino’s theater. Quentin Tarantino’s a fan. And I thought there’d be 12 people but it was packed. It was so packed there were queues around the block for standing room only. And during the screening, people were clapping and cheering and laughing all the way through it, not in a sarcastic, ironic kind of way, but genuinely. It was gratifying to see that love after all the hate.