The Oral History of Spider-Man: The Animated Series, the Ambitious Cartoon That Changed Everything

In 1994, Spider-Man was forgotten, neglected, and about to be reintroduced through a peerless animated series. Here's how it all came to be.

In 1994, Spider-Man was down on his luck.

His various comic book lines were being slowly consumed by the infamous “Clone Saga,” which would come to represent Marvel at its height of desperation and excess. James Cameron was developing a feature film based on his adventures, but the project was destined to collapse. And while he remained synonymous with ’60s camp in the television world, Batman and the X-Men had been adapted into massively successful and thoroughly modern animated shows.

But on Nov. 19, the Web-Head’s fortunes finally began to change. After months of development chaos, Spider-Man: The Animated Series premiered on the Fox Kids Network. Immediately, it became a hit. A new generation had been introduced to the iconic character and his universe.

“It’s hard to believe now ... but back in ’93, young kids didn’t know who Spider-Man was.”

“It’s hard to believe now, because now I drive down the street, I see little kids with Spider-Man backpacks and little Spider-Man hoodies,” showrunner John Semper tells Inverse. “But back in ’93, young kids didn’t know who Spider-Man was.”

Thirty years since its debut, Spider-Man: The Animated Series’ influence remains profound. Sam Raimi’s Spider-Man film trilogy drew heavily from its interpretation of pivotal characters and storylines. In its final story arc, the show pioneered the “Spider-Verse,” which Sony Pictures has now expanded into two major box office hits. More recently, at the end of Marvel’s X-Men ’97, the show’s incarnation of Spider-Man appeared in a surprise cameo.

But how did such a seminal vision of the webslinger come together in the first place? To answer that question, Inverse spoke to the show’s creative team.

A Rough First Draft

The beginnings of Spider-Man: The Animated Series were a little troubled.

In 1993, following the success of X-Men: The Animated Series, Fox Kids began to explore the possibility of a similar cartoon adaptation for Spider-Man. By 1994, the network had joined forces with a new studio, Marvel Films Animation, to bring the series to life. As production began, the late Marty Pasko, a writer and story editor who had won an Emmy for his work on Batman: The Animated Series, was chosen to run the show. But conflict soon emerged between him and other parties. As the situation deteriorated, Semper, an ardent Spider-Man fan who was working on the PBS series The Puzzle Place, was contacted by Stan Lee.

John Semper: The thing about running a show is that it’s about 25% talent and 75% politics. It’s just unfortunately the way it works out. I liked Marty [Pasko]. I knew that Marty was talented, but Marty was kind of like a big teddy bear. He was not someone that I thought was a people-handling person. Marty had not had any real history of running shows.

Robert N. Skir (freelance writer on Spider-Man: The Animated Series): [Marty Pasko] wanted to do a very faithful adaptation of the first 140 issues of the comic book. It’s like “This is going to be the most authentic Spider-Man series ever.” But Marty’s a very opinionated person. I think that if Marty had been a little more flexible and diplomatic, he probably would have stayed with the project longer. But God bless him. He had these passions, and I agreed with him. I was heartbroken when he left, because I loved his vision.

“I thought, ‘What the hell have I gotten myself into?’”

Semper: Months go by. And then I get a call from Stan [Lee]. And he says, “We’re in trouble. It’s not working out with Marty.” I dropped everything, broke my contract on Puzzle Place, and came over to Marvel Films Animation, which was a new company that they formed for the sole purpose of making Spider-Man. I left a really good gig to come to absolute chaos.

So I get there, and I said, “OK, well what have you got so far? What’s Marty done?” Well, it turned out that whatever he had done, I couldn’t see contractually based on their exit deal with Marty. So I’m literally starting the show from scratch. They’ve got maybe a month before they have to go into production. They have to have a pilot within about four weeks. I thought, “What the hell have I gotten myself into?”

Marty wanted to hire a whole bunch of comic book guys to write Spider-Man. And I thought, that’s not a bad idea. Let’s try that. So I called up and introduced myself to Gerry Conway, bless his heart.

Gerry Conway (writer, “Night of the Lizard”): By 1994, I was actually writing a lot of mainstream television. I had been invited to write episodes of [Batman: The Animated Series], which I did just for fun. I wanted to be part of that. Having written the Batman show, or a couple of episodes of it, it seemed only fair to write a Spider-Man episode. And to my surprise, I ended up working on the pilot.

We met with Stan Lee, who was overseeing or contributing to the show. Might have been John [Semper], might have been me, but I think it was Stan who suggested the Lizard as the first villain for the pilot episode, which made a lot of sense to me because visually, he was a great-looking character. I don’t recall whether I’d written him in the Marvel books or not, but he was one of my favorite characters when I was a kid reading Spider-Man.

The usual procedure for a show like that was to pitch an idea, develop the idea into an outline with the producer, and then write a script. John was involved at each stage of that. And then, of course, he had to take it over because my commitment was only to do a first draft.

I think it was Stan who suggested the Lizard as the first villain for the pilot episode, which made a lot of sense to me because visually, he was a great-looking character.

Semper: I hired Gerry [Conway] to do “Lizard,” because as a showrunner dealing with all this stuff, I didn’t have time to write. So I thought, I’ll just hire a good, solid writer. Gerry did a great job with the first draft. It went through many, many, many rewrites and I rewrote every script. I was the last pair of hands on every script. Somehow we muddled our way through “Lizard.”

Conway: I would say much of what ended up on the air was John [Semper]’s work. The Lizard I remembered from my childhood had made a pretty good impression on me. And I think that's what I tried to capture. I tried to keep the dialogue fresh, but still true to the character. I love writing Peter Parker and Spider-Man. The voices are very familiar to me.

Semper: By the time we got to the end of “Lizard,” I had pretty much given up on the comic book writers. Avi [Arad of Toy Biz, the company manufacturing the toys that would accompany the series,] came to me and he said, “Spend money; hire writers; get people; bring in a staff.”

Stan Berkowitz (staff writer on Spider-Man: The Animated Series): I came in in the middle of [“Night of the Lizard”]. I think I only came in at the last draft. And then we were all assembled in a meeting with Avi. And we were finally done with it after all these drafts. And he looked at Gerry [Conway] and says, “You know, I’m really happy with this.” And Gerry just looked at him sourly and said, “I had nothing to do with this draft.” I think it was because the script had gone through so many drafts just to make everybody happy. I worked with [Gerry] later, and he’s just one of the nicest people.

Semper: [“Night of the Lizard”] went through a lot of hands. The biggest change that I remember was that initially the ending was going to take place at the Daily Bugle. There was going to be a big fight at the Daily Bugle and the printing presses were going to be thrown around. Somewhere down the line, somebody said, and it might have even been Avi, “Why don’t we go into the sewers for the big ending?” And I thought, well, of course, that makes sense.

The Room Where It Happened

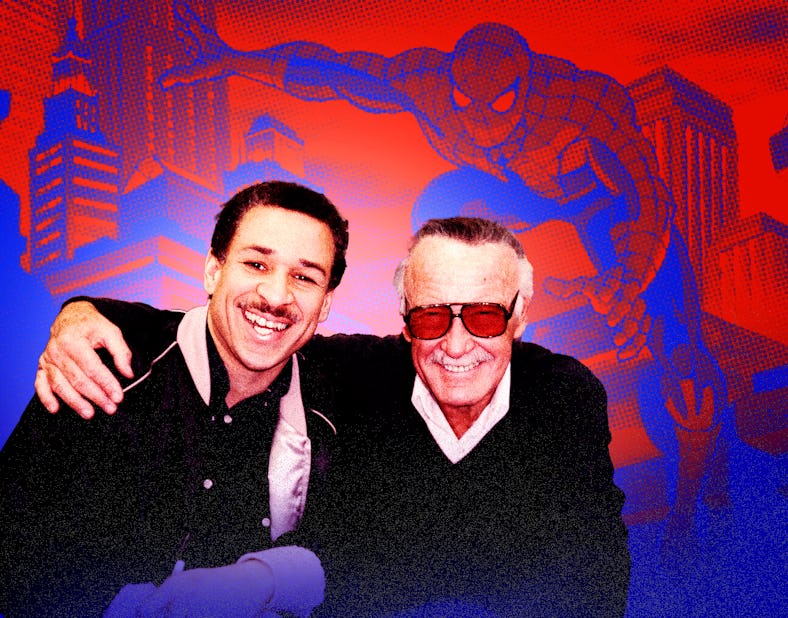

Executive producer John Semper with Stan Lee.

As the show’s first season came together, Semper found himself entangled in a conflict between various figures: Stan Lee; Avi Arad; supervising producer and director Bob Richardson; and Sidney Iwanter, a representative for Fox Kids.

Semper: The show was very much a group effort for Episodes 1 through 12. And we went over everything in excruciating, long table-read meetings that seemed like they would go on forever. We had all these factions. And I had to juggle all of that.

Berkowitz: There were a lot of competing interests, everybody giving notes on certainly all of the scripts in the first season. Once everyone had a sense of what the scripts are going to look like, it became easier. But during that first season, a lot of tempers were on edge and it was very difficult.

Mark Hoffmeier (staff writer on Spider-Man: The Animated Series): Early on, if you’re making a show, especially a show like this where you’ve got 65 episodes, you're going to have network execs, and you’re going to have producers like Avi [Arad], and you’re going to have both writers and writer-showrunners like John [Semper] and me. And you’re going to have Stan [Lee], who had an office in the building. Early on, Stan would be very involved. Stan would give notes.

We would have meetings where everybody would get involved and sort of discuss “What are we doing?” And we’d sit around and some of those meetings would go eight hours. … Literally all day we’d be in a room talking about story.

A page from a Spider-Man: The Animated Series script.

Berkowitz: Everybody was trying to make the show their own unique vision. And the visions, although they differed very slightly, even that slight difference is enough to create friction. What’s funny is that the differences were so minor, so minute. And yet the fights — I won’t say the fights were bitter, but they were certainly protracted. They went on for a long time. And that’s why it took so long to eventually get the first scripts in place — “Lizard” and the Venom saga and all that — because of very minute adjustments. People really fought. Again, not bitterly, not insultingly. But there was friction. And the irony is that everybody wanted the same thing — they wanted a successful show.

Brynne Chandler (freelance writer on Spider-Man: The Animated Series): There was a lot of arguing, but I don’t think it was just weenie-waving. I think that each one was actually passionate about what they wanted.

“This is Spider-Man, this is a teenager, this is a young guy, and he’s got issues.”

In addition to the main writing staff, Semper hired several freelance writers to contribute to the first season. These included Brynne Chandler, the duo of Brooks Wachtel and Cynthia Harrison, and the returning duo of Robert N. Skir and Marty Isenberg.

Brooks Wachtel (freelance writer on Spider-Man: The Animated Series): All in all, Fox Kids was a good team. They didn’t dumb the shows down. It wasn’t Super Friends, everybody laughing at the end of the episodes. No funny animals. It wasn’t juvenile. We were doing stories that within certain limitations you could do on prime time. They were that good.

Cynthia Harrison (freelance writer on Spider-Man: The Animated Series): Stan [Lee] did keep reminding us: This is Spider-Man, this is a teenager, this is a young guy, and he’s got issues. He’s so insecure. He’s bumbling, fumbling. Never forget that. He’s not confident. He’s always doubting himself. And that’s what was really fun to write. He’s very imperfect, and that’s what makes him such a popular character because people can identify with that so much.

Marty Isenberg (freelance writer on Spider-Man: The Animated Series): There were so many eyes and so many notes and so many directions that the show was being pulled in that by the time it got through to a production draft, and things would change beyond that too, it had gone through so many changes. And then you can see it in the credits on the show, how many names get story credit and script credit. It frankly got to just be ridiculous. But I think those credits are pretty accurate. Those scripts, particularly those early scripts, went through a lot of fingers.

“We’ve got a hit!”

Spider-Man: The Animated Series debuted and was a near-instant sensation.

By the time production on Spider-Man: The Animated Series’ first season concluded, the show was a clear success.

Berkowitz: Once that first episode aired, everyone looked at it and said, “OK, we’ve got a hit. I can shut up now.” And the pressure became less from everyone because they thought, “Well, yeah, it’s working.” So everyone seemed to be happy that the show was doing so well. And it really did well. I mean, the only competition that it had on Saturday morning was X-Men.

Semper: [We did the] first 13 episodes totally in the dark. You don’t see any footage, none. The closest you get to an animated cartoon is the recording session and hearing the actors perform, but you don’t see anything. It was around Episode 13 that we started getting footage in on “Night of the Lizard,” and then all of the important guys no longer wanted to be in the writing room with those boring meetings. They wanted to be in the editing room.

Episode 13 [“Day of the Chameleon”] was a stand-alone, but I really started feeling the spirit of the show. And then [Episode] 14, boom, we take off, and that’s because they left me alone. They were playing with that toy, and Avi [Arad] came to me and he said, “I think you can handle it now.” I said, “Oh, thank you so much.” And then that was it. I took off.

With his creative control increasing, Semper decided the show’s remaining seasons would each follow an overarching story rather than the first season’s “villain of the week” format.

Hoffmeier: We writers were sort of left to our own devices, and that’s when we started doing what I see as the really groundbreaking thing. We had long story arcs. We had story arcs going over multiple episodes, which you now see on streaming services. But back in the day when we were doing it, that was strongly discouraged. You didn’t want to have to air an animated show in a specific order, because depending on when the animation was coming back from overseas, you wanted to be able to “Oh, OK, we got Episode 4 ahead of Episode 6, we’ll just plug that in this week.”

We were imposing an order on things [with season-length story arcs] like “Neogenic Nightmare” [in which Spider-Man tries to rid himself of a disease that’s slowly transforming him into a grotesque “Man-Spider” creature] and “Sins of the Fathers” [in which the Green Goblin slowly emerges and seemingly kills Mary Jane Watson, Spider-Man’s love interest]. We’re imposing an order on these that certain people didn’t like. But because we had hashed all that stuff out at the beginning, now we had freedom to be able to do stuff like that. And I think John [Semper]’s vision for doing that was very forward-thinking.

“The essence of the Spider-Man comic book was, to a certain degree, soap opera.”

Semper: And then we start with Episode 14, which is [where] the whole [“Neogenic Nightmare”] mutation arc [begins], and the Punisher. And I still watch that Punisher episode. I get chills because that was the episode where the show became what I wanted it to be. That was it. I had always wanted the show to have a continuing storyline. I was adamant about it because that was the way the comic book had been, and I wanted the show to have the spirit of a comic book. You can’t actually translate a comic book to screen. But you can give the essence of the comic book.

And the essence of the Spider-Man comic book was, to a certain degree, soap opera. Peter Parker dealing with the loves of his life and dealing with the pressures. I always told my writers, “This is not a show about Spider-Man. This is a show about Peter Parker. Spider-Man is just one of the many complications in his life. So let’s not ignore Peter. That’s the most important thing. All the explosions and the fighting and all that stuff, that’s fun. But it’s Peter Parker’s show.”

I’m like, “Oh, my gosh.” That was crazy. It was Silvermane, but he was turned into a baby because of the neogenics, but he needed to turn back into an adult.

Berkowitz: The problem we were always having with scripts is they were too long. It’s like, “Put all this sh*t in and make it shorter.” Like, how do you do that? So it’s like, “Do you really need Rhino in here? Because we’re already running long. But yeah, cram it in, cram it in.” And you feel that compression. It was on a different episode where Iron Man and War Machine I think flew in, they did this, then they flew out. And I said to John [Semper], “We’re running long; it’d be really easy to cut this out.” He goes, “No, you can’t do that.” And then he explained to me the importance of selling toys to our financing.

Ernie Altbacker (staff writer on Spider-Man: The Animated Series): We jammed a lot of stuff in there. It was fun! [John Semper] always wanted [to go] big on cameos and wanted to put in the max amount of story. And sometimes I think he got crap, because at that point, there was this kind of false narrative around that would go “Well, this is too high-level storytelling for kids.” But whenever I found out that kids could know 200 Pokémon characters and their three different levels of changes and stuff, I'm like, “They can follow this just fine.”

Jim Krieg (staff writer on Spider-Man: The Animated Series): Honestly, if this was a live-action show, any of those episodes would be at least an hour long. We would do an hour’s worth of material in 22 minutes. So Spider-Man talks fast. There’s always something happening. There’s really no breathing room. And it’s a rush because you have all these ideas and things that you’re acquiring from the comics that you want to see realized as well.

If you see other shows from that time, they’re not necessarily paced that way. I think that there was just a lot of story that John [Semper] wanted to tell. So we told it as quickly as possible. And then once you're in that groove, that becomes the normal pace of the show.

Harrison: I know that for one of [our] episodes [“Partners”], they just kept adding. And I’m like, “Oh, my gosh.” That was crazy. It was Silvermane, but he was turned into a baby because of the neogenics, but he needed to turn back into an adult. But then there was also Smythe’s father, his body was shriveling, and then Vulture and Scorpion. It was like, “OK, and who now? Oh, and now we’re throwing in another one. Add this one and make sure to add this one.”

“ This is a show about Peter Parker. Spider-Man is just one of the many complications in his life.”

Wachtel: And then we’re like, “We already have the Black Cat as a co-star.” There was the whole B-story of the relationship between Spider-Man and Black Cat and their romance. And she was wondering if he was just using her because she was helpful in the fights.

Harrison: And we had to choreograph the fights. That was crazy. And it was like, what can we do? It can’t all be the same. That’s why …, like with Scorpion and Vulture and this one and that one, it’s like, “OK, what are all their powers and how do we choreograph the fight again? What would they be doing to use against the other?” And that was a lot, much more than just writing an episode, but directing it. All the camera angles, you had to write that in.

Wachtel: Animation writing is very detailed because in live action, you can write the fight and the stuntman will come in, and they'll work it out. But in animation, it has to be on the page.

The Seinfeld Effect

When Seinfeld became popular in the early 1990s, its multifaceted approach to storytelling proved influential on other shows. Spider-Man was no exception.

Altbacker: John [Semper] would do the writing what was called the Marvel way, where we wrote the shots for the storyboard artists. They could do it differently. But we were expected to give a viable take on what the visual should be and camera angles. Some of those scripts were 40, 45 pages, which doesn’t happen anymore. Now it’s like everything’s written like Seinfeld or a feature script. And the animators will break it down.

Krieg: I think it’s [“Hydro-Man”] where what I wrote was, “Mary Jane flags a taxi, and it pulls over, and she gets in and drives away.” And then Spider-Man has a line. And that’s exactly what they drew. A cab pulled up. There was no driver. She gets in the driverless cab and it pulls away magically. Now, in today’s world, that could actually happen. But at the time, it seemed like somewhere someone along the way would have said “Is there a driver in the cab?”

Hoffmeier: John [Semper] got Stan Lee to buy into the kind of storytelling that Stan actually inspired, these multiple storylines and these multiple things. And that was also the early days of Seinfeld. And so John used Seinfeld as an example to say, “Look, they’re doing all these multiple stories; multiple things are going on in just a half hour.”

“Stan comes in and goes, ‘I watched this show Seinfeld, John, and they tell all these stories. It’s fantastic!’”

And it was so funny because at one point in time, I remember Stan came into John’s office talking to me like, “So many things are going on. These stories are all over the board.” And John said to Stan, “Have you seen this show Seinfeld?” So the next week, Stan comes in and goes, “I watched this show Seinfeld, John, and they tell all these stories. It’s fantastic!” And John was like, “Yeah, Stan, that’s what you did. You did that all the time.”

Semper: I don’t think Fox was terribly excited about the fact that I was doing continuing storylines, but that’s what I wanted to do. I think the great saving grace of the series is that it does follow a continuance. You can watch it from beginning to end, and it’s a complete story. I had a tremendous amount of control over the show. I would figure out the arc. I’d call a writer in, and I’d say, “I want to do this story. Let’s figure it out.” So we’d sit there, and we’d work it out together.

Let’s examine the Man-Spider arc. I went to the writers, and I said, “I want to do a thing where Peter is suffering from some kind of disease.” And then Mark [Hoffmeier] actually said, “Maybe he’s turning into Man-Spider!” And I said, “That’s exactly right.” You have to know when you hear a good idea. Strangely enough, a lot of inspiration would come just from the comic book covers. I’d look at a cover, and I’d go, “Oh, yeah, we have to integrate the Kingpin into this show. That’d be a good one to do.”

Krieg: John [Semper] had it all in his head. He didn’t even have it out on the serial killer map with the yarn and the photographs. He knew what he wanted to hit when. Sometimes, if you developed your story, it didn’t really fit into the arc particularly neatly. So there was always just some sort of tip of the hat. Even in “Hydro-Man,” the first episode I did, [Spider-Man] mentions at the beginning, “I might be getting sick with this mutation disease.” And that’s it. You forget about it the whole time until the end. So sometimes, it was just a tip of the hat to keep the story alive. But that’s how all shows are, even today.

Hoffmeier: What John [Semper] spent a lot of time doing and what we spent a lot of time discussing was “OK, we have these individual stories, but we’re laying them out in the framework of what this season is. If it’s ‘Neogenic Nightmare,’ what is all the connective tissue throughout these episodes? And how many scenes do we need to insert in these episodes to service that overarching story for the season?” Even if someone from outside had brought a script back in, then we would have to rewrite or add scenes that we had determined would service that ongoing storyline for that season.

“Spider-Man doesn’t hit people”

A scene from Spider-Man: The Animated Series.

Like other animated shows of its times, Spider-Man faced restrictions from Broadcast Standards and Practices (BS&P). Though these were often humorous, Semper believes their effect on the show has been exaggerated.

Hoffmeier: One of the things John [Semper] did that was great was he ordered complete runs of comic books from Marvel. We had huge filing cabinets full of comic books. And sometimes we’d just go through the comics looking for stories because occasionally you'd have stories rejected. I think we proposed a Ghost Rider story — no, no, no. Man with his head on fire? No, we don’t want to have children lighting their heads on fire and riding their big wheels.

I remember we got pushback with our Daredevil episode: “Can we call him something other than the devil?” He’s not the devil; he’s the Daredevil. It’s a different meaning. “Can we not have the little horns on his head? Can you make those look like ears? Can his suit not be red?”

“X-Men had censorship. Batman, when it was on Fox, had censorship. Power Rangers was banned in Canada.”

Semper: I have to say this. I used to go to conventions, and for a joke, I would read the BS&P notes. And what I didn’t realize, because I didn’t see the advent of the Internet coming, was that somehow by highlighting this, it would make it sound like only my show had any kind of censorship, which is total ridiculousness. X-Men had censorship. Batman, when it was on Fox, had censorship. Power Rangers was banned in Canada. We all had the same degree of censorship, per se. We all had to work around it in different ways or ignore it or get on the phone with Avery Coburn — our BS&P person — and argue, which I hated to do.

And the other thing was “Oh, Spider-Man doesn’t hit people.” Well, that’s me. I just didn’t believe that modeling for young kids, hitting was something that I needed to be showing a whole lot of in a Saturday morning cartoon show. And Spider-Man has webs; he doesn’t need to hit people. So we did it when it was necessary, like at the end of “The Spot” when his fist comes out of the hole and socks the guy. It was necessary. It was a good little plot point. I had Mary Jane slap Peter at the end of the Chameleon episode. I wrote that. But by and large, I just wasn’t very big on hitting. And I’m proud of that.

Berkowitz: We’d get notes all the time about excessive violence and making the violence fantasy. Like rather than giving someone a gun that fired bullets, give them a laser or a ray gun that couldn’t exist in real life.

The thing that got me occasionally was dialogue and language. To have one character call another character an idiot, we couldn’t do that. Idiot used to be a literal medical term, just as moron was a medical term. Those were literal medical terms in use, I guess, as late as the 1940s. But we couldn’t use those. So often someone would say, “Oh, you fool!” You'd have to call someone a fool, which you could be. It's not a literal thing. You couldn’t say kill, death, or murder, and you couldn’t have people actually die, either, except Uncle Ben.

Krieg: [In “Hydro-Man”], Mary Jane’s being stalked by her ex-boyfriend, Morrie Bench, who coincidentally has been turned into a supervillain who can turn himself into water. The first note we got from BS&P was “The element of stalking is not viable for this script. We cannot address that.” I was like, “Well, that’s kind of the point of the script.” I think what we did was we took out the word stalking and kept it exactly the same. Because it was like an issue at the time. And I wanted to fight them. I wanted to say, “You know, the point of it is that Spider-Man is against stalking. It is a serious issue, but we're coming out against it. It’s not a pro-stalking episode.”

“Spider-Man is ... the greatest Spider-Man show that could have been made at that particular moment. And the greatness of it is still resonating throughout the cinematic universe.”

On network television, people can’t swear. So when Spider-Man is in Washington Square Park and he sees the fountain explode and convert into Hydro-Man, what’s he going to say? So he says “Kumbaya!” which was Eek the Cat’s catchphrase at the time. I think it’s in “Six Forgotten Warriors” where Vulture flies out of the prison he’s being held in and realizes he’s in Russia. And he says, “Good heavens, I’m in Chernobyl!” “Good heavens!” is what we got.

Altbacker: It was funny. We would get these notes and we would laugh at it, but it seemed like it wasn’t done in an even-handed way, even between channels. Batman: The Animated Series, they had guns; they had breaking glass. You can’t break glass on the Spider-Man show. Nobody ever goes through a window. If a building explodes, it’s tough glass; it doesn’t break. If there’s a car crash, it’s not breaking any glass.

I remember getting a note like “Please do not have the Kingpin pick Spider-Man up by his head.” I’m like, “Let me do something that I haven’t seen before. He’s going to just pick him up by his head with one hand, right?” And they did not like that. That did not make it in.

“Spider-Man has webs; he doesn’t need to hit people.”

Krieg: One of the first notes I ever got, and this was just to kind of prepare you for a lifetime of notes, was that in this fight with Hydro-Man, Spider-Man gets knocked from one rooftop all the way to another rooftop. He lands on a pigeon coop, and then the pigeons were to go flying. And the note I got from the network was “Spider-Man does not hurt animals.” I don’t remember if that’s still there. But if it is, I’m sure we made clear that every single pigeon got out of that coop before he landed on it.

I did an episode with Stan Berkowitz where we introduced Carnage to the waiting public. And Carnage, in his alter identity, he’s a serial killer, Cletus Kasady. But we couldn’t say the [words] serial killer. I guess he would have to be like a serial harmer. You had to talk about it in the vaguest terms — “He’s a bad hombre!” I don’t think you ever have any idea that he’s supposed to be Hannibal Lecter.

Carnage, in his alter identity, he’s a serial killer, Cletus Kasady. But we couldn’t say the [words] serial killer. You had to talk about it in the vaguest terms — “He’s a bad hombre!”

Semper: It’s like guns. BS&P didn’t let us do guns, and they wanted us to do ray guns. And then I thought, “Well, if I were going to do a gun, how would I do it?” And then I thought “I want to do an episode where Robbie Robertson’s kid gets a gun.” First of all, it’s Robbie Robertson, like a pillar of everything that’s good and right and moral. He’s got this kid who’s being an errant teenager and running around with the wrong crowd. And he gets his hands on a gun, and I can maybe say some things about what that’s like and what that’s all about. And Randy’s got a gun. We open up the drawer; we see a gun. It’s a gun. I mean, these people who are like, “Oh, they never did guns on Spider-Man.” It’s a gun. We did it. But that was a challenge.

The Long Goodbye

“You did not see Peter actually getting together with Mary Jane. And I did that purposely in a way because that really wasn’t what the story was about.”

After five seasons, the show’s last episode, “Farewell, Spider-Man,” aired on Jan. 31, 1998. In its final moments, Spider-Man’s mentor, Madame Web, transports him through time to find Mary Jane Watson, who had vanished at the end of Season 3. Their reunion was not shown on screen.

Semper: I always read this: “Spider-Man ended on a cliffhanger.” No. I didn’t do that. What I did was I did not resolve… You did not see Peter actually getting together with Mary Jane. And I did that purposely in a way because that really wasn’t what the story was about.

The story, the big arc, was about Peter becoming a man and valuing himself. Having certainty, having self-confidence. He gained all of that after saving all of reality. And then he meets his creator, and he says, “I’m not the guy you created, Stan. I’m not that guy anymore.” And Stan says, “Wow, you really aren’t that guy.” That was all purposeful. And then Madame Web says, “Let’s go meet Mary Jane.” I couldn’t have been more plain than that. It may be unresolved on some level, but it’s not a cliffhanger. No one was in jeopardy at the end of my series.

“My mandate was to always surprise the viewer.”

Krieg: We were certain that we’d have 100 episodes. John [Semper] had a whole thing planned out where Madame Web was going to take Peter into the past and they’d find Mary Jane. We had plenty to do. By that time, there were a lot of things going on at Fox Kids, and I think the idea was “Oh, let’s do something else.” And I think it was a foolish idea because we had a hit show. Just keep making the hit show. That’s my philosophy.

Semper: Could I have added a scene where he met Mary Jane? Well, I suppose in the back of my mind I was thinking “What if we get miraculously picked up for 10 more episodes? This might give me a decent arc to start off with.” And I had some ideas about where I wanted to go with it. I had this sort of vague idea that Peter would go on a quest to find Mary Jane and that that might involve him going through time. Beyond that, I don’t know. Things would have occurred to me. I would have had to come up with an entirely new reason for Peter to be insecure about something. And then we would have tried to resolve that, figure that out.

My mandate was to always surprise the viewer. That was the most important thing to me. And what I love about Spider-Man is that it is the greatest Spider-Man show that could have been made at that particular moment. And the greatness of it is still resonating throughout the cinematic universe. That to me is the greatest tribute — they still can’t let go of what I did in my series. I did everything I wanted to do. I walked away with absolutely no regrets.