The new Scream is Craven in all the worst ways

The fifth entry in this once-subversive meta-slasher series should be the franchise’s last gasp.

Do you like scary movies? How about franchise follow-ups?

Not a straight reboot, nor quite a sequel, the new Scream — which confusingly shares a title with the first film — instead positions itself as a twice-as-cynical hybrid of the two. It's a “requel,” uniting veteran characters with fresh faces to extend its franchise’s lifespan incrementally and harken extensively back to the original.

Is this more proof of Hollywood’s inability to invest in new ideas and rest any once-lucrative property that retains a shred of brand recognition? Count on it. Another attempt to sate audiences with an empty-calories promise of a trip down memory lane? Definitely. But as the commercial success of Star Wars: The Force Awakens, Jurassic World, and Ghostbusters: Afterlife makes clear, requels can be big business.

In the case of this fifth entry in the once-subversive meta-slasher series — the first not directed by franchise architect Wes Craven, who died in 2015 — that means Sidney Prescott (Neve Campbell), Gale Weathers (Courteney Cox), and Dewey Riley (David Arquette) are all back, and for more than a fleeting cameo.

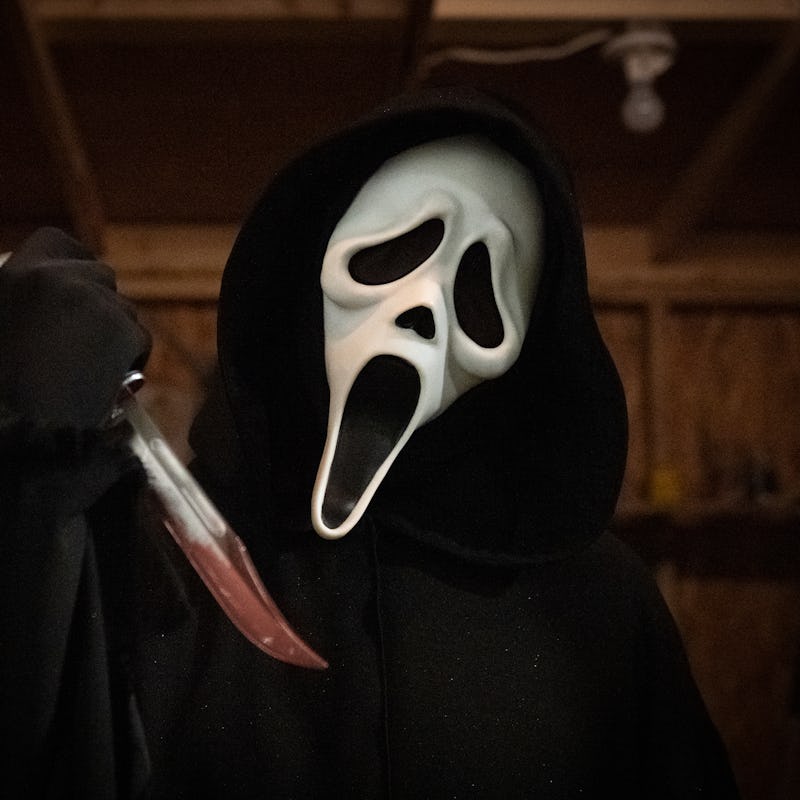

The original Scream trapped its characters and a few horror-obsessed acquaintances in a slasher movie of their own that, thanks to a knife-wielding maniac in a Ghostface mask, proceeded regardless of everyone’s familiarity with the genre. And much as Jamie Kennedy’s resident fanatic Randy armed the first Scream’s teens with a set of time-honored rules for surviving to the end — no sex, no substances, no saying “I’ll be right back” — this new Scream, as directed by Matt Bettinelli-Olpin and Tyler Gillett (Ready or Not), takes pains to school its new blood on what it might take to survive Ghostface.

There will be no answering the phone while home alone, no going down into darkened basements, and absolutely no failing to background-check loved ones, among other such foolhardy acts. Of course, the old-timers in attendance need no such refresher.

Reuniting in Woodsboro after a lengthy three-pronged reintroduction, Sydney, Gale, and Dewey seek to protect the troubled Sam (Melissa Barrera, In the Heights), whose sister (Jenna Ortega, You) and boyfriend (Jack Quaid, The Boys) are among those stalked by Ghostface. Naturally, the killer’s motive is tied up in a dark secret from Sam’s past, a secret that connects her directly to a pivotal character from the first Scream.

“It always goes back to the original,” stress horror-buff twins Mindy (Jasmin Savoy Brown) and Chad (Mason Gooding), who themselves are related to Randy.

Dylan Minnette as Wes, Jack Quaid as Richie, Melissa Barrera as Sam, and David Arquette as Dewey Riley star in Scream.

The new characters mainly serve to connect this Scream back to its same-named progenitor, also tackling the bulk of the film’s meta-commentary. Early on, one lays out the concept of a “requel,” and another sings the praises of “elevated horror.” In the world of Scream, both terms speak to a new generation just as horror-literate as its predecessors but more openly dismissive of the genre’s overall quality — especially where slasher sequels are concerned.

That’s in part because the fictional, in-film Stab series — which turned the bloody events of the first Scream into a hit horror franchise in Scream 2 — is now on its eighth installment, and ardent fans of the earlier entries have soured on the franchise’s recent direction. But it’s mostly because the main subject in this new Scream’s sights is fandom itself: more specifically, an abusive subsection of fandom where passion has curdled into childish rage and toxic entitlement.

The new Scream largely fails to imbue its new characters with personality or soul.

And yet the new Scream — as scripted by James Vanderbilt and Guy Busick — doesn’t carve up this deserving target with anything resembling the original’s ruthless audacity. Offering pale imitations of its self-referential humor, their copycat approach feels instead more akin to fan-fiction, authored by individuals who’ve considered Scream in only the most generic-possible terms and written all their characters to conform to that same base understanding.

For instance, sorely missed in this Scream are the uniquely witty temperaments of the original characters. For all their deep-bench references and ultra-wry back-and-forths, the likes of Sydney Prescott and Randy Meeks were too dynamically written (courtesy of original Scream scribe Kevin Williamson) to ever sound like mouthpieces. But the new Scream largely fails to imbue its new characters with personality or soul, and out of the younger cast members, only Savoy Brown and Gooding display enough presence to make a meal out of their scraps.

Ghostface and Jenna Ortega in Scream.

This new film also suffers due to its continued investment in Stab, initially introduced as a playful meta flourish but here keeping Scream at an ironic distance while denying its satire a real-world edge. Whenever characters bemoan the waning qualities of Stab sequels, which is often, it’s a riff on a riff, signifying nothing.

The same can be said for the film’s endless callbacks to the original Scream, which feel both obligatory and obnoxious. The franchise has always been engaged in a tonal high-wire act of sorts: between scary and silly, referential and derivative, brazen and shameless. Dismayingly, this is the first Scream to come down almost exclusively on the wrong side of those equations, falling into the exact pitfalls it surmises to be plaguing franchise filmmaking right now. It earns few plaudits for pointing this out.

Jokey one-liners about the derivative nature of requels and the fan service-y gambit of bringing back “legacy characters” can’t cushion the not-so-slight betrayal of watching Scream commit to that very course. That includes its bizarre CG-assisted cameos and supposedly significant character deaths that shock only in how unaffecting they are. Some of these requisite sequel touches were perhaps once intended to be delivered with a knowing wink, but Bettinelli-Olpin and Gillett’s flat direction plays it surprisingly straight. And the snarky dialogue — littered haphazardly throughout the film’s ungainly structure — is for once not sharp enough to speak for itself.

Ghostface in the new Scream.

Craven had a wicked ability to deconstruct genre tropes without lessening their tension or impact. A horror maestro who’d previously delivered one slasher icon in Nightmare on Elm Street’s razor-gloved Freddy Krueger, he knew the genre deeply enough to satirize it with exhilarating force. The same can’t be said for Bettinelli-Olpin and Gillett, whose limp work behind the camera does little to salvage the story and especially fails the kill sequences. These are staged unimaginatively and feel staid rather than savage.

Craven’s aptitude for foreshadowing, the deft style with which he could manipulate audiences into suspecting a killer behind every closed door, is nowhere. Instead, the exasperating slapdashery of Bettinelli-Olpin and Gillett’s installment directly contrasts the artistic thoroughness with which Craven approached the series.

This film is dedicated to Craven’s memory. And in a sense, its existential pointlessness — the new Scream’s failure to do more than dutifully restage sequences Craven executed more effectively 26 years ago — stands as a testament to the filmmaker’s massive talent. But for such a fate to befall Scream of all franchises is the only irony worthy of him. Too absent an identity of its own to achieve any meaningful self-awareness, yet too motivated toward this goal to realize it’s digging its own grave, this new Scream leaves the franchise spinning in a void. It’s meta static.

Scream opens in theaters on January 14.