You need to watch the best sci-fi cult classic on Amazon Prime ASAP

Catch this piece of movie history.

Night of the Living Dead changed the course of horror movies, which really means that it changed the course of movie history in general. Commercial filmmaker George A. Romero, based out of Pittsburgh, had cut his teeth shooting segments for kid’s show Mr. Roger’s Neighborhood, including an episode where Mr. Rogers gets a tonsillectomy. But he wanted to try something new, something that would capitalize on the moviegoing public’s insatiable desire for the bizarre.

He was inspired by a novel he had read earlier, Richard Matheson’s I Am Legend, which would eventually become its own movie three times over. Romero was struck by the loneliness its protagonist felt in a world where everyone else had become vampires. Despite originating the modern zombie movie, Romero had very little interest in what specific form the threat to humanity came from, as he would tell CinemaBlend in n 2008 interview:

“I couldn’t use vampires because he did so I wanted something that would be an earth-shaking change. Something that was forever, something that was really at the heart of it. I said, so what if the dead stop staying dead?...I didn’t use the word ‘zombie’ until the second film and that’s only because people who were writing about the first film called them zombies.”

Night of the Living Dead prefers the equally horrifying terms “ghoul” or “flesh-eater” to describe who is doing the killing. But no matter what term is used, or perhaps even because so little attention is paid to the origins of its antagonists, Night of the Living Dead remains one of the scariest movies of all time.

Night starts with siblings Johnny and Barbara’s trip to the cemetery, the movie takes its time in establishing that they are about to enter horrifying circumstances. Visiting their father’s grave, Johnny reminds Barbara of when he used to scare her as a child, and shouts out “They’re coming to get you, Barbara” in a mocking tone that gives the viewer a sense of their entire relationship.

Judith O'Dea in the cemetery

Of course, they actually are coming for Barbara. The ghoul knocks Johnny aside and begins chasing her, and the viewer really feels this sense of sudden terror in Judith O’Dea’s performance. Barbara flees the scene, desperate for some relief from the stranger. That’s when she finds the house and the film starts to shift. Suddenly, the movie introduces us to its other protagonist, Ben.

George Romero has said several times that the casting of Duane Jones as Ben had less to do with the racial politics of America and more to do with who he could afford to cast and the quality of Jones’ audition. But as Richard Newby notes in an essay on the movie for The Hollywood Reporter, “every aspect that horror had taught audiences about black men — that they are unimportant at best, and rapists of white women at worst — is tossed aside as it becomes clear that Night of the Living Dead is Ben's story rather than Barbara's.”

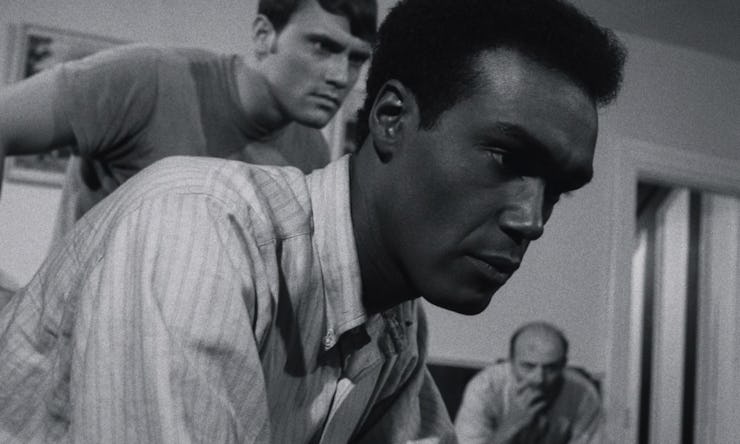

Duane Jones gives a quiet, determined performance that would stand out for decades to come

What follows would then set the tone for horror movies for decades to come. Characters representing different viewpoints are suddenly thrown together and forced to cooperate or die. It’s easy to see Romero’s film as a look at race relations in America, with Ben and the white Harry Cooper battling out for strategy as the stakes rise and rise.

Another genre film would come out in 1968 that would change the course of movie history. Stanley Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey challenged viewers with abstractions, asking them to consider man’s evolution and the nature of humanity’s relationship with the Universe. Night of the Living Dead is almost 2001’s polar opposite, challenging the viewer directly with a clear sense of metaphor. “Work together or die,” it seems to be saying.

Until the ending.

Ben and Harry dislike each other from the start, and things get worse.

Although it’s been over 50 years since Night of the Living Dead, it’s hard to match the movie’s ending. The way Romero builds tension, and the fate of Ben, are devastating. Roger Ebert saw the movie in 1969 in a theater filled with kids who were expecting a typical monster feature. As the film ended, Ebert writes:

The kids in the audience were stunned. There was almost complete silence. The movie had stopped being delightfully scary about halfway through, and had become unexpectedly terrifying. There was a little girl across the aisle from me, maybe nine years old, who was sitting very still in her seat and crying.

I don't think the younger kids really knew what hit them. They were used to going to movies, sure, and they'd seen some horror movies before, sure, but this was something else.

Shot on a minuscule $114,000 budget, Romero had tapped deep into the American psyche. The film would become a global phenomenon, grossing over $12 million, and Romero had a clear future. Movies would spend years trying to catch up.