How the guys behind RoboCop changed action movies forever

And why they're struggling to keep up in 2020.

Few mainstream action sci-fi movies satirize modern society as perfectly as RoboCop, which is why there’s still life in the franchise 33 years later.

Original screenwriter Ed Neumeier is returning to write and produce a new movie, something he's been planning since the 1987 original. "It's a direct sequel at this point,” the 63-year-old writer tells Inverse, “We're ignoring the other features and taking the characters somewhere after the first movie ends."

After Robocop’s release, the 1988 Hollywood writer's strike tripped up Neumeier and co-writer Michael Miner’s plans for an immediate sequel, but he's now working off the same basic premise, just updated for modern sensibilities.

RoboCop made Neumeier a misnomer of sorts. He was an outsider who was inside the system. He was and remains a smart satirist who commanded multimillion-dollar budgets (as he would a decade later in Starship Troopers). He used the language and forms of American movies to comment on the poor state of the American body politic, and executives didn’t seem to care that it was all a send-up.

“Right now, I don’t think I could make a movie like Starship Troopers,” Neumeier says. “In fact, probably nobody in Hollywood really wants to. Movies cost more, the marketing costs more and the sweet spot is global and high gloss entertainment, so everything gets pretty manicured. You don’t want to offend people too much.”

Welcome to the Inverse Superhero Issue! Read more here.

Neumeier (left) and Verhoeven (right) with two of the stars of 'Starship Troopers.'

RoboCop also made a subversive Hollywood player out of Dutch director Paul Verhoeven, who paired Neumeier's social commentary with the requisite thrills and spills audiences loved.

Verhoeven grew up in Nazi-occupied Holland, so his taste for satirizing fascism is deeply ingrained. Meanwhile, Neumeier’s childhood couldn't be more different: He spent his formative years in 1960s Northern California. Picture George Lucas' American Graffiti, which by coincidence was shot in and around Neumeier’s hometown.

But despite the thrills of rock and roll and drag racing around him, the shadow of Vietnam was never far away, and it exposed him to that most perennial of wartime institutions – propaganda. Soon becoming one of his primary interests, Neumeier’s influences coalesced years later when he came to write 1997’s Starship Troopers, based on the 1959 book by Robert A. Heinlein.

"Heinlein would have seen all the movies from the 1940s I watched as a pattern for Starship Troopers, movies like Wake Island, Action in the North Atlantic and Air Force,” Neumier says. “I wanted to make a movie that had that form, if you will."

A new kind of cop

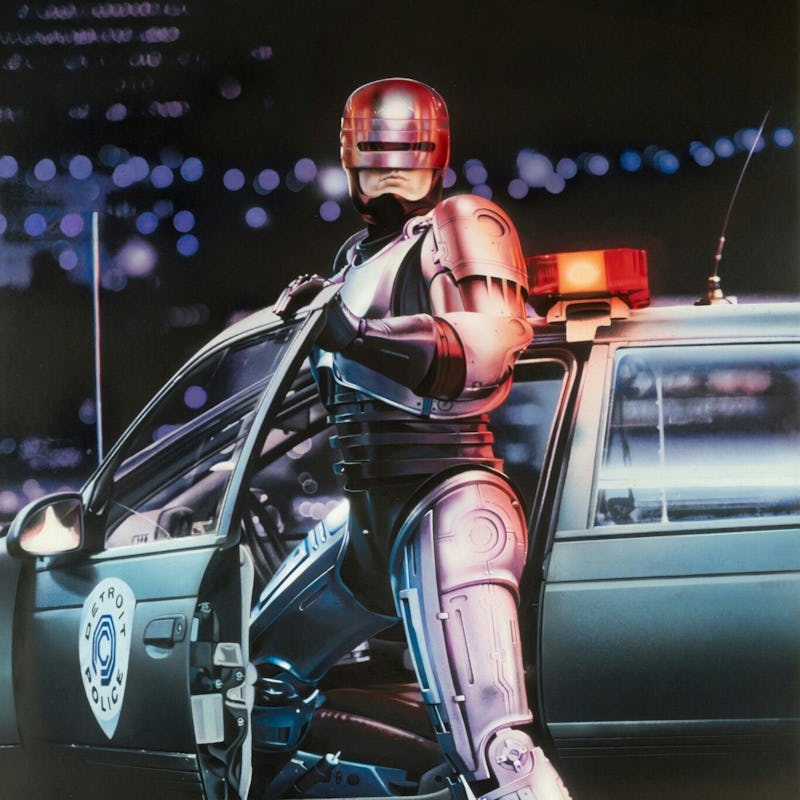

'RoboCop'

But long before Starship Troopers, while working as a studio development executive in the mid '80s, Neumeier had an idea about a cybernetic police officer on the streets of Detroit and the military-corporate-industrial complex that turns out to be worse than the criminals on the streets.

He'd written most of the script, but meeting emerging filmmaker Michael Miner gave him the creative jolt he didn’t know he needed to get it finished. Neumeier and Miner bonded over the films they liked and decided to team up on the script that became RoboCop. Then came producer Jon Davison (Airplane!), who understood Neumeier and Miner's intent and took the script to iconic ‘80s production company Orion Pictures (The Terminator, Platoon), who similarly loved it. The search for a director was on.

Paul Verhoeven, who'd been making adult dramas successfully in his native Holland since the early ‘70s was sent the script.

He didn’t even finish it.

"I read about 15 pages and threw it aside," the director tells Inverse. "I called Mike Medavoy at Orion and told him I didn't want to do it. But my wife Martine read it because she wanted to know why I didn't want to do it and said I should reread it."

Not nearly as comfortable working in English those days, Verhoeven tried again with a dictionary by his side. And this time, something clicked.

"The scene that convinced me was where he goes back to the house and sees flashbacks of his wife and child,” he says. “That was the most emotional to me and I thought I could keep that idea alive throughout the whole movie. It was so precisely and beautifully phrased."

“In RoboCop, we emphasized violence in general. I discovered it was fun!” — Paul Verhoeven

Then there was the more prosaic script element that caught Verhoeven’s attention. For the Media Break segments – where eternally perky newscasters keep you up to speed with OCP, Detroit's crime wave and Delta City – Verhoeven referenced the geometric shapes of Dutch painter Mondrian.

"We did [Media Breaks] three or four times throughout the movie,” he says. “I thought I could make them interesting from a stylistic point of view."

One of 'RoboCop's media break scenes.

Verhoeven was inspired by the work of Dutch artist Piet Mondrian.

Lights, camera...

Verhoeven later surprised everyone – including himself – by directing kick-ass action scenes like RoboCop’s first night on duty, the “melting man” and ED-209’s tragic malfunction.

"It wasn't the reason to do the movie, the philosophical underpinnings of the script attracted me,” he says. “But it turned out I could do action very well."

Realising he had to figure the genre out, Verhoeven turned to The Terminator for inspiration. "It had come out a year or so earlier so I basically studied the action and editing. Cameron was always very fast and sharp, it was extremely well done, so when we had action in RoboCop we emphasized violence in general. I discovered it was fun!"

'The Terminator'

'Robocop'

Like he had with Miner, Neumeier found a kindred spirit in Verhoeven. Of particular distinction was the director's propensity to depict bloody and high-impact violence – including the threat of sexual violence – as frankly as possible, something you'd almost never find an American director doing in the 1980s.

"That was one of the things we really agreed on," Neumeier says. "I'd always liked movies like Dirty Harry and The Wild Bunch. Paul and I had a very similar sensibility that way."

Both men knew they'd work together again in a heartbeat. Neumeier thinks Verhoeven elevated what was in the script, and Verhoeven calls Neumeier a virtual co-director who was involved during every stage of production.

They got their chance again a decade later in Neumeier's script for Starship Troopers, both adapting and pillorying Heinlein's notorious right wing screed. The result was the perfect blend of big screen spectacle using the latest filmmaking technology and a barely veiled comment on the tendency of powerful governments to embrace nationalism and pursue perpetual war for perpetual peace.

Crucially, both writer and director knew the thrills were as pivotal as the parody.

"After Jurassic Park came out, I told Jon Davison we'd always wanted to do Starship Troopers," Neumeier says. "Now we had CG [computer generated imagery], we could get Phil [Tippett, special effects maestro] to do the bugs and Paul to direct. I didn't even have to finish the pitch, [Jon] thought it was a great idea."

But where Orion understood RoboCop a decade earlier, Sony didn't really get Starship Troopers. “There had been a regime change at Sony so it was almost like a white elephant for the people who'd inherited it, they had no idea what to do with it,” Neumeier says. It seems someone somewhere figured good looking kids in military garb fighting giant CGI bugs on another planet might result in a Star Wars-sized box office.

"Jon had pretty good relationships [at Sony] and nobody had ever bought the rights to the book, so we were able to get it," Neumeier says. "That was a four or five-year period of writing and getting the movie up and running, then it took a year and a half or two years to make it and cut it. It was a enormous undertaking."

And how. Starship Troopers cost $105 million (about $170 million today), and held the record for the highest number of computer generated VFX shots – Jon Davison remembers there being around 600 when Inverse asked him.

It also cemented the place of CGI in Hollywood. Jurassic Park included around 50 special effects. Starship Troopers had 500.

Why so serious?

'Starship Troopers'

But while RoboCop and Starship Troopers are great fun, they depict pretty grim futures — Verhoeven's dystopian classic Total Recall (1990) rounds out the trilogy. After growing up seeing the Gestapo throw neighbors in vans never to be seen again and V2 rockets raining terror from above, maybe he's just a pessimist.

"Without negativity, there's no drama," Verhoeven says. "And of course, if you look around at the universe, it's violent. Every step you make you kill ants. You can see the universe is violent in those photos by the Hubble telescope. If you dare to look the universe in the eye, you see violence.”

“If you dare to look the universe in the eye, you see violence.” — Paul Verhoeven

The only thing more important to Verhoeven’s worldview than violence? Sex.

"And without sex we wouldn't be there,” he says. “Violence and sex are dominant elements for drama. I'm not inventing anything new, those two elements have always attracted me because they're also the truth."

So now, with RoboCop having been sequelized, rebooted, and currently being re-sequelized again with Neumeier on board, and Starship Troopers star Casper Van Dien pushing hard for a reboot, it's worth remembering that both films were perfect for their times.

RoboCop came when Reaganomics had revealed itself to be about siphoning wealth from the middle class and leaving them to fend for themselves in declining urban centers, and fed off society's concerns over the rapid ascent of technology.

Starship Troopers came just in time for a right-wing militaristic government to take hold in the US, chasing enemies it branded as subhuman into caves in far off deserts – just like the Federation. Today, even the Bush years pale in comparison with the ugly hysteria of the Trump era politics of hate. How can we possibly make an effective sociopolitical parody when we live in one?

"We can do something with [the current political climate], but if you are in the middle of it as we are now, you might be completely wrong if you do a screenplay now," Verhoeven says. "There were things Ed and I discussed and laughed about because we thought they could never happen. There's a chance every big country will go in a right-wing fascist direction. We didn't think it would happen like that in the US, we really thought we were doing science fiction. In retrospect, we were closer than we thought."

Welcome to the Inverse Superhero Issue! Read more here.

This article was originally published on