“Down and dirty”

Road House director Rowdy Herrington breaks down the movie’s most absurd scenes — including, of course, the throat rip.

The night before Road House started production, Rowdy Herrington thought he was going to be sick.

After a family dinner, both his son and his wife had come down with food poisoning, and the green director, embarking on his first major studio movie, assumed his stomach would betray him, too.

“I didn’t sleep a wink,” Herrington tells Inverse. “All I could think of was, I’m going to go there and say action and throw up — and they’re going to say the kid folded.”

But the next morning, when Herrington arrived on set, he found honeywagons, grip trucks, and hundreds of crew members all waiting for him. He couldn’t bow out now. He swallowed his sour feeling and — like the characters he’d soon be directing — forged ahead through the pain.

“I just said, ‘OK, let's go.’”

“It’s really so broad. And, in many ways, down and dirty.”

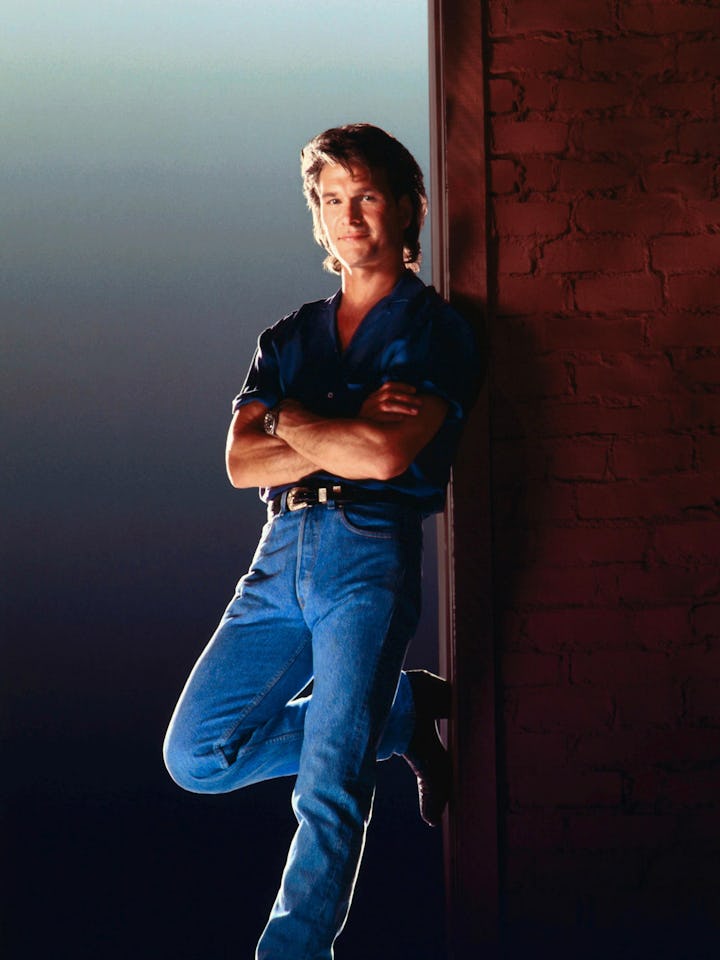

Thus began the creation of one of the wildest, cheesiest, and most violent cult classics of all time. At its most basic, Road House, which debuted in theaters in May 1989, follows the exploits of Dalton (Patrick Swayze), a mythical and nationally-renowned “cooler” (basically a bouncer), who’s recruited to Jasper, Missouri, to clean up The Double Deuce, the town’s biggest and most dangerous dive bar. In the process of turning the establishment into a smoother operation, he butts heads with wealthy bigshot Brad Wesley (Ben Gazzara) and his gang of goons, who initiate a series of bloody brawls to try and scare Dalton out of town. “It’s really so broad,” Herrington says. “And, in many ways, down and dirty.”

No ’80s action movie was more grimy — and absurd — than Road House.

Over its riotous and raunchy two hours, there are massive explosions, absurd car stunts, ludicrous one-liners, topless women, bruising beat downs, an electric soundtrack, and countless smashed beer bottles. Oh, and arguably the movie’s most famous climactic moment, a ripped-out throat.

Before producer Joel Silver convinced him to helm the project, Herrington thought the script had gone too far. But he also recognized its classic structure and relented to the producer’s plea to take it on. “This was a Western,” Herrington says. “You’ve got the gunslinger coming to town. He’s got to meet the bad guy running the town, who’s got his own gunslinger to go head-to-head at the end.”

Everything else — Swayze’s sweaty and sculpted body, the ridiculous martial art melees, the lack of any law enforcement — is quintessential ’80s action flick icing. Maybe that contributed to the initial negative reviews (“Gene Shalit called it Outhouse,” Herrington laughs), but Road House has only gained more esteem over the last three-and-a-half decades, filling up retrospective screenings with audiences just as rambunctious as the bar patrons on screen. For its 35th anniversary, and on the tails of the release of Doug Liman’s revamped Road House, we broke down the original’s most absurd moments with Herrington — and got to the bottom of that infamous throat rip.

The First Double Deuce All-Hands Brawl

The scene: When Dalton first arrives at The Double Deuce, he leans back onto the bar to audit how the bouncers and wait staff handle the nightly roughhousers. The answer? Not well. After just a few minutes, two men get into a fist fight (after one of them pimps out his wife) that spills into a handful of tables. In an instant, the majority of the bar starts throwing haymakers and beer bottles at people’s heads. As the live band shreds guitar from behind a cage, Dalton can’t help but shake his head at the property destruction and large-scale wrestling match unfolding.

The details: Thanks to stunt coordinator Charlie Picerni and kickboxing stuntman Benny Urquidez, Herrington felt pretty confident about turning a sound stage into a makeshift ring — and making sure he got a few laughs in between the violence. “What I asked for were the moments where the waitresses got into it and were whacking people,” he says. “The funny guy at the bar who’s watching it all laughing — he gets whacked.” Before the fight, Herrington and Picerni walked through each sequence at half-speed, allowing the director to shotlist each punch or table snap and determine when to include some wide shots. “I had an idea for what I wanted to see for each part of that fight,” he says.

Dalton’s Riverside Tai Chi

The scene: As he settles into life in Jasper, Dalton spends his mornings centering himself before a long night of kicking out troublemakers. Across the river, Wesley, his villainous neighbor, can’t help but snicker at his new enemy’s glistening torso.

The details: Herrington wanted to express Dalton’s peaceful inner philosophy in a non-verbal way. (After all, he tells Dr. Elizabeth Clay, his love interest played by Kelly Lynch, that “nobody ever wins a fight.”) Tai chi, Herrington felt, would do the trick. So he enlisted his wife, Toni Semple, who taught the ancient practice, to work with Swazye and get the movements just right.

“The whole idea was that Patrick was a spiritual character,” Herrington says. Later, before Dalton and Elizabeth have sex, they engage in a slow dance across his lofted bedroom, choreography that worked as a nod to Swayze’s recent turn in Dirty Dancing. “It was actually Joel’s insistence. He said, ‘Let’s see a little dancing as they’re making love,” Herrington says. “[Patrick] was smart. He was a great actor. He was a great dancer. He was a martial artist. He was a musician. I mean, he did everything.”

The Loading Dock Fight

The scene: After a couple of failed attempts to take down Dalton, Wesley’s gang rounds up a couple of bigger and taller heavies to rough him up and smash the bar’s supply of alcohol. Luckily, Dalton’s longtime pal Wade (Sam Elliott) arrives just in time to extricate him from this outnumbered scenario, throwing one assailant into a literal dumpster and sending some others home with torn-up kneecaps.

The details: With each fight (there are nine in total), Herrington wanted to up the ante and build toward the finale. “Sam just saunters in, looking around, like what’s going on here? And he kicks everybody’s ass,” Herrington says. “That was the way we wanted to introduce the reunion between Patrick and Sam.” Despite it being an awkward area to orchestrate a lot of bodies, Herrington and Picerni scoped out moves based on the dialogue (“because those were the beats that made you understand the characters,” he says) and made sure the martial arts combinations got more complex and punishing. “I asked the casting director to only give me guys in Brad Wesley’s gang who could fight, who had martial artist training. And that made Charlie’s job easy.”

Red’s Auto Parts Store Explosion

The scene: To tighten his grip on the town, Wesley has one of his men commit arson on Red Webster’s shop. The building blazes for everyone at The Double Deuce to see, improbably exploding a few times until the entire property is ashes.

The details: It didn’t really matter if the fire bombs were logical. At least, not to Al Di Sarro, the movie’s special effects coordinator, who was dead-set on using up his pyrotechnics budget. “If he didn’t work in the movie business, he’d be in jail for arson,” Herrington laughs.

“I said, ‘Well, what will be there after the explosion?’”

“Toothpaste,” Di Sarro replied.

The Monster Truck Demolition

The scene: When Wesley gets word that some of the town’s leaders plan to end his financial reign, he commands his gang to drive a Bigfoot monster truck through Jasper’s glass-sheltered car dealership. Nearly running over customers inside, the towering truck shatters the entire structure and smushes a few show cars in the process.

The details: Herrington only had one shot to get this scene right, so he utilized seven cameras to capture the demolition derby. After discussing the setups with cinematographer Dean Cundey, Herrington covered both ends of the dealership, placing one camera on a backside crane and a small 35-millimeter camera underneath the truck itself. The actual stunt was supposed to take around 45 seconds, but the truck bulldozed through the building so fast that one of the crane operators had to jerk the camera up at a moment’s notice. “[The truck] came so fast, it scared the shit out of him,” Herrington says. “He’s looking through the camera and he thought that truck was going to hit him.”

The incident spooked him so much, Herrington recalls, “we had to send the operator home.”

The Throat Rip

The scene: The movie’s most iconic moment begins after Wesley’s top henchman, Jimmy (Marshall Teague), sets Dalton’s neighbor’s house on fire. In retaliation, Dalton sprints, leaps, and tackles Jimmy — trying to get away on his motorcycle — in mid-air. The pair then engage in some brutal martial arts combat. As both men struggle to get the upper hand, Dalton throws a few final haymakers and reverts to his signature move. He grabs Jimmy’s throat and rips out his larynx, killing his opponent before pushing his dead, bleeding body into the river.

The details: To start the fiery scene, Herrington wanted Swayze to sprint out of his bedroom window, so he had the crew build a plausible attached roof to the barn. “Jumping like that was hard for Patrick,” Herrington says. “He had that knee issue — he had to get his knee drained twice — but he was all for it.” Though Swayze did the vast majority of his own stunts, the director couldn’t afford to have him leap onto a moving motorcycle. After all, he needed Swayze to save his energy for the extended fight with Teague, a martial artist who eventually taught his co-star the choreography with Picerni while mostly staying in character. “I know Patrick is a method guy,” Herrington says. “I have to assume Marshall was, too, because at lunch, these guys are staring at each other across the lunchroom like they’re going to kill each other.”

Over two nights, Swayze and Teague shot their riverside fight, but the script didn’t indicate how it should end. That’s when Herrington thought back to college, where his roommate had told him a story about a martial artist mentor who had gotten surrounded by a gang one night. “Some guy came at him with a knife and he blocked the knife and did this puncture of the throat, pulled the guy’s trachea out,” Herrington recalls his roommate telling him. “I said, ‘What happened?’ He said, ‘The guy died.’” Herrington soon pitched the idea to Swayze. “I wanted some kind of parallel between what happened in the past and this [fight],” Herrington says. “Patrick was all for it.”

“You had a martial artist who was that good and he had to defend his life and needed to kill the guy. And that’s how he did it. That was the death blow,” Herrington adds. “The idea was to make it as realistic as you could, even though it’s pretty outrageous.”

The Driverless Exploding Car

The scene: After Wesley’s men kill Wade, Dalton plans a surprise attack. He sticks a knife into his Mercedes’ accelerator and steers it toward Wesley’s home, where his goons are standing guard ready to shoot. They eventually scatter as the car barrels toward them, ramps over a fence, cannon rolls, and explodes in mid-air, quickly rolling to a burning stop.

The details: Though nobody is driving the car in the movie, Picerni tapped his son to get into the vehicle and execute the mid-air explosion. “It actually was supposed to land on its roof, but he was going so fast, he went all the way over [and landed] on his wheels,” Herrington says. “We ran over, put the fire out, and everyone got him out. He was fine.”

The Final Showdown

The scene: Dalton finally gets his revenge inside Wesley’s taxidermied home, which is filled with dozens of animal heads and hunting trip photos. This time, Swayze turns into the hunter, taking out his opponents one by one before Red and a couple other town leaders each unload their shotguns into Wesley’s torso.

The details: What makes the scene work is the absurd amount of stuffed exotic animals hanging throughout Wesley’s house. The location scouts found the home in Los Angeles, but they didn’t need to do much set dressing (except for the taxidermied polar bear that falls on top of one of Wesley’s men) because the owner was already a big game hunter.

“He had everything he killed. I mean, it was a museum of murder,” Herrington recalls. “There were two snow leopards that were endangered species that he had shot and stuffed and had in this cutout by a stairway. I thought he was a sick guy.”

Considering how many stunt people and extras were involved in the project, Herrington notes that only one injury occurred throughout the entire production: a broken ankle, when a stuntman falls from the balcony inside Wesley’s home. “They had a big mattress and a bunch of cardboard boxes and he flipped over too far and landed on his feet,” Herrington says. “I sent him a big bottle of Irish whiskey.”