One of the Worst Bond Films Could Have Been One of the Best

A Bond Odyssey.

No one wants to hear that the book is always better. It’s a lazy, boring argument that misunderstands how narratives move between mediums. Besides, it’s often not true — would anyone argue that Peter Benchley’s novel is better than Jaws? The claim is often just snobbery... but when it comes to the 1979 James Bond movie Moonraker, the book really was better.

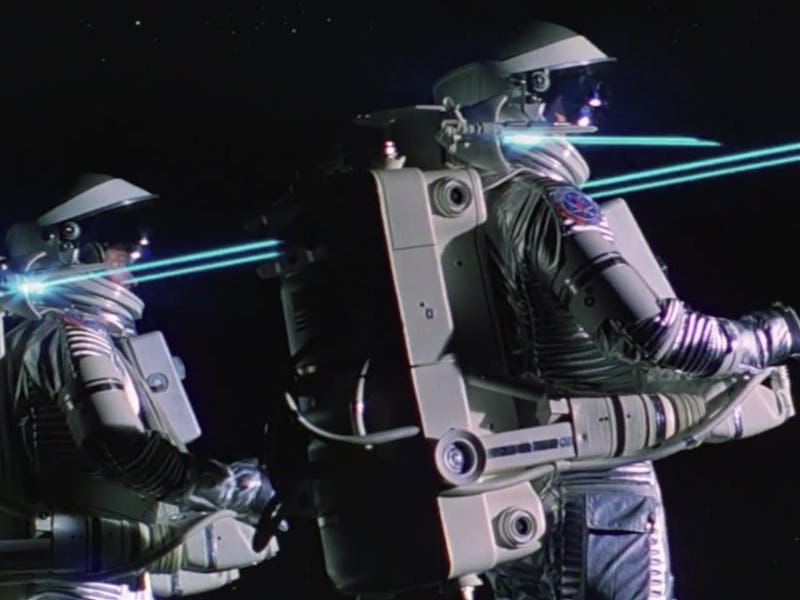

Moonraker is such a frustrating Bond film (and sci-fi film) because, for 45 years, it’s given the novel of the same name a weird reputation. When we hear “Moonraker,” we think of Roger Moore making out in zero gravity, or perhaps the powerful laser weapon in the GoldenEye game. Moonraker, as a movie, is a fun Bond flick, but its title is associated with high camp and derivative sci-fi ideas. And, on some level, Star Wars is to blame.

Moonraker begins with a space shuttle of the same name being hijacked during transport. The shuttle’s design is a clear homage to NASA’s space shuttle, which, at the time of Moonraker’s 1979 release, hadn’t flown yet. These design details, and the early revelation that the space shuttles are built by megalomaniacal billionaire Hugo Drax (Michael Lonsdale), are all aspects of the film that not only work, but hold up better in 2024 than in 1979. While making Moonraker, longtime Bond producer Albert Broccoli said, “This is science fiction as we’re shooting it. But by the time the film’s out, it will be science fact.”

Broccoli was referring to the space shuttle technology and the advent of spacecraft that could land like conventional aircraft. But what feels more prescient about Moonraker now is its use of Hugo Drax as the driving force behind this new chapter of spaceflight. In 1979, an eccentric billionaire building space shuttles was one of the more outlandish aspects of Moonraker. Today, Elon Musk is practically a Bond villain.

Bond’s investigation into Drax feels equal parts plausible and hyperbolic, and it’s these elements that are drawn from Ian Fleming’s 1955 novel. In the novel, Drax is a private citizen who’s developed a nuclear rocket capable of protecting the United Kingdom from missiles. This plotline, which predated the Reagan-era Strategic Defense Initiative by three decades, also felt like sci-fi, but what makes the novel so compelling is how grounded it is.

Hugo Drax, Moonraker’s Elon Musk-esque villain.

The third Bond book ever published, Moonraker starts with Bond and M trying to figure out why Hugo Drax, a self-made millionaire, is bothering to cheat at cards. After a tense game of bridge between Bond and Drax, 007 is assigned to investigate Drax’s rocket site on England’s south coast. He’s teamed with an undercover police officer named Gala Brand, who, unlike the hapless Bond Girls of so many films, is Bond’s equal. She even rejects his romantic advances.

In the movie, Roger Moore’s Bond is paired with Dr. Holly Goodhead (Lois Chiles), an astronaut and undercover CIA agent. That’s a fun premise, but Goodhead never matches Brand’s competency. Notably, the novel never sent Bond to space, which was the entire goal of the film. The closing credits of Moore’s second Bond movie, The Spy Who Loved Me, claimed, “James Bond will Return in For Your Eyes Only.” But after the astounding success of Star Wars, the franchise felt like it needed to send Bond to space first.

Moonraker isn’t the worst Bond movie, or even a particularly bad 1970s sci-fi action flick, but it contains none of the intelligence and vulnerability of the novel. Bond and Brand’s adventure is filled with emotional interiority, although they do get tied up under some rocket engines in the end. It's one of Fleming’s tighter books, and it reveals a softer, more realistic side to James Bond. It’s also a story with strong opinions on the ultra-rich who believe they’re allowed to dictate world affairs.

Look familiar?

The Bond franchise has a general distaste for the billionaire, with Hugo Drax being a particularly good example. The book reminds us that Bond is essentially working-class compared to Drax, and the reader’s sympathy for 007 is brilliantly layered. In the film, it feels like Bond and Drax are both upper-crust types, so the film relies on Bond Villain tropes from previous movies to get the job done. It’s effective, but not affecting.

With Star Wars shooting sci-fi into the stratosphere, the movie needed to get Bond into space, which left subtlety and character work on the back burner. Instead of being one of the most grounded Bond films, Moonraker became one of the least plausible. When Bond did return in 1981 in For Your Eyes Only, the franchise made a hard pivot back into relative realism and credible stakes. But in 1979, 007 was lost in space.