“third, it must possess originality.”

Is Star Wars sci-fi or fantasy? How George Lucas changed “science fiction”

Science fiction isn't want it used to be. Literally. Star Wars changed the definition of science fiction forever. Here's why

by Ryan BrittSci-fi is exactly like rock music.

Depending on who you ask, different people believe different definitions of science fiction apply. For most, concocting the secret formula for "real" science fiction tends to be similar to a statement uttered by Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart in 1964 — "I know it when I see it." Justice Stewart was trying for a legal definition of obscenity, but coming up with a water-tight definition of science fiction can be just as tricky.

So what is science fiction anyway? Many have attempted this — and written entire books about it — but just for the hell of it, we're gonna try to do it in two thousand words or less. And the fastest way is to talk about Star Wars. You've probably heard people say Star Wars isn't "really" science fiction or that it's "just science fantasy."

But Star Wars is science fiction. Even if it didn't use to be.

I'm using Star Wars as the example here, mostly because it's the most contentious. Few people would argue that Star Trek — Star Wars' predecessor in the mainstream —isn't science fiction, though in the late '60s and early '70s literary SF gatekeepers argued it wasn't good science fiction. "None of these programs deserve serious consideration as SF," John Baxter writes dismissively of Star Trek (and most sci-fi TV) in the 1970 book Science Fiction in the Cinema. In terms of book-first sci-fi people, Baxter wasn't alone in his opinion at the time, and early Trek fans were greeted with more than a little hostility from the more bookish establishment

Still, any resistance Star Trek met from SF gatekeepers is a very different semantic argument from Star Wars. Star Trek's sci-fi cred may get questioned by so-called experts, but by any new (or old) definition of "science fiction," it's always qualified. Even critics who hated it (like Baxter and Sam. J. Lundwall) still felt compelled to include the original Star Trek in their non-fiction books about the history of science fiction.

Obviously, haters try to conflate the two questions "is this good science fiction" with "is this science fiction," but these are different questions. Both questions can elicit aggressive answers from grumpy people. The following is a handy way to talk to those grumps.

Is Star Wars sci-fi?

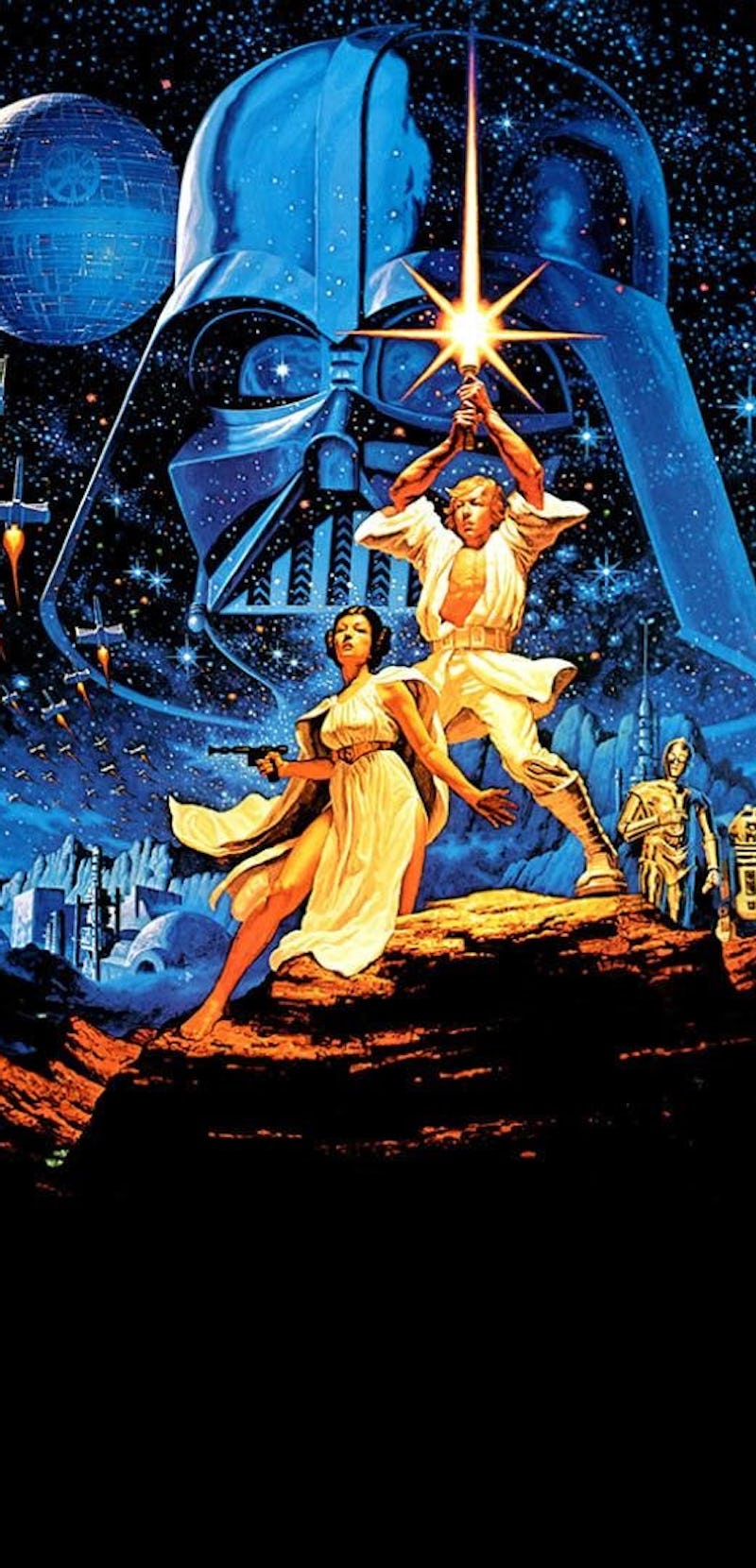

The classic Star Wars gang in 1977.

Star Wars is weird because it's the most famous science fiction thing of all time that often rejects its association with the term "science fiction." George Lucas has even said: "Star Wars isn't a science-fiction film, it's a fantasy film and a space opera." Literally, everyone smart who comes to the Star Wars-isn't-science-fiction-party tends to drink from one of three different bottles:

- Star Wars is really fantasy

- Star Wars doesn't speculate about technology, therefore isn't about "science"

- Star Wars is a "space opera."

Each of these arguments is compelling, but all three are largely semantic and ignore that the notion of a separate genre called "science fiction" is barely a century old. So using taxonomy from before 1977 is slightly silly.

Classifying Star Wars as not science fiction requires everyone to agree on the rules of what science fiction "really" is. But this is oddly backward. The only reason this argument persists into the 21st Century is that Star Wars staunchly refuses to drop the "science fiction" label in Disney+ or TV Guide descriptions. The monoculture actually knows something that hardcore SF scholars (and George Lucas) refuse to accept. Star Wars changed the broader definition of science fiction and there's no turning back.

The argument that Star Wars isn't sci-fi is emotionally compelling for many reasons. For one, it lets people who view science fiction pejoratively still enjoy Star Wars without having to hold it to certain standards. It also allows science fiction literary purists to wash their hands of mainstream culture. Anytime something like Star Wars (or Star Trek) is dismissed as not "real" science fiction, the argument cuts both ways. Depending on the person, Star Wars is either too good for that gross silly genre of science fiction OR science fiction is too good for Star Wars.

Saying Star Wars isn't "real" science fiction is exactly like saying Lil Nas X's "Old Town Road" isn't a real country music song. You can kind of see where people are coming from, but at the end of the day (the 21st Century), it's close enough?

What’s the earliest definition of science fiction?

This monkey in space is totally sci-fi.

The genre of science fiction is much older than the term "science fiction." Some historians cite Mary Shelley's Frankenstein as the first science fiction novel, while others would claim that oral stories spoken by the real-life Cyrano De Bergerac count as even earlier versions of the genre. But in the interests of only fighting about the origin of the term itself, science fiction was predated in Western literature by the term "scientific romances," which were mostly used to describe the works of H.G. Wells or Jules Verne.

It wasn't until 1926 when editor Hugo Gernsback used the term "scientifiction." His famous magazine, Amazing Stories, was originally subtitled "The Magazine of Scientifiction." According to Alternate Worlds: The Illustrated History of Science Fiction by James Gunn (1975), Gernsback described Amazing Stories and "scientifiction" like this:

"The formula in all cases is that the story must frankly be amazing; second it must contain scientific background; third, it must possess originality."

At face value, this definition is pretty good! The famous Hugo Awards — the literary sci-fi version of the Oscars — were named in honor of Hugo Gernsback, and with fairly good reason. The Encylopedia Britannica stops short of saying that Gernsback invented the terms "science fiction," but most historians (and dictionaries) credit him with popularizing the term.

Although Amazing Stories didn't start until 1926, Gunn notes that Gernsback tried to start a magazine called Scientifiction in 1924. But after mailing 25,000 letters soliciting subscriptions to said magazine, and receiving less than stellar-response, he decided he needed a better title. Thus, Amazing Stories was born.

So two things to think about next time you're fighting about the definition of sci-fi: 1) the first science fiction magazine couldn't even bring itself to be called science fiction and needed, desperately, to slap the word "AMAZING" on there to get people to pay attention. And 2) even the "father" of science fiction realized sci-fi needed to pretend not to be sci-fi. This is why this debate will never end. Science fiction kind of hated its own name. At least at the beginning.

What’s the difference between sci-fi and science fiction?

Can this spaceship appear in something that isn't sci-fi?

The short answer to this question is: There is no difference. But practically speaking, there's a huge difference.

The term "Sci-Fi" is a portmanteau that shortens the words "science" and "fiction" but also alludes to the term "Hi-FI," short for "high fidelity." Basically, sci-fi is a cutesy media abbreviation of science fiction, which, many SF authors objected to for a very long time. (For some literary-minded "serious" science fiction people, "SF" refers to what is written, or what is real science fiction. Making matters worse is the fact that the larger umbrella term — "speculative fiction" — has the same initials as SF.)

Do people who write SF (or sci-fi) books today care about these differences? Some of them do. I'd argue that most of them don't, but the "Star Wars isn't science fiction" debate sometimes leads to someone busting-out the term "speculative fiction." This is something Margaret Atwood has jokingly called "No-Martians science fiction." Basically, your drunk friend who thinks Black Mirror is "Speculative Fiction" and not "Science Fiction" might make this argument.

The problem is, with the exception of Margaret Atwood – a writer who clearly has written science fiction novels, but has successfully rejected the label — most "speculative fiction" and "science fiction" isn't different enough when you go macro. So, are you Margaret Atwood? Have you written both The Handmaid's Tale and Maddaddam No? Well, then I think you're in a bad position to explain the "difference" between spec fic and science fiction.

Again, in a literary critical sense, I know my statement can be easily "disproven." But I'm not playing by academic rules. Because, for a regular person, it is very hard to weave an energy barrier between "speculative fiction" and "science fiction" and convince everyone it's actually there. Trying explaining the difference to a teenager who loves Star Wars and enjoyed reading Ready Player One. Go ahead, try.

In his book The Jewel-Hinged Jaw: Notes on the Language of Science Fiction, Samuel Delany makes this point: "The words content, meaning, and information are all metaphors for an abstract quality of a word or a group of words." In his famous essay "Science Fiction," Kurt Vonnegut commented that science fiction is a "lodge" composed of people who "love to stay up all night arguing the question 'what is science fiction?'"

How Star Wars changed science fiction

Is sci-fi a visual medium?

Prior to the seventies, science fiction had not gone truly mainstream. In the sixties, Star Trek established that the medium of science fiction didn't need to be books or magazines, and in 1977, Star Wars solidified that fact. If you do a quick Google of "science fiction genre" you'll find that the first result classifies it as a "Television Genre." Is Google wrong?

Well, yes. Science fiction isn't just a TV genre, but, in terms of the ways in which most people interact with it, sci-fi is a visual medium. Remember when Egon says "print is dead" in Ghostbusters? Well, in terms of how the culture at larger thinks about science fiction, SF books are not the predominant way the culture interacts with the genre.

Somewhere, someone is rolling their eyes because they are saying my entire argument for proving that Star Wars is science fiction is based on the fact that populism changed the definition of science fiction because of Star Wars. And to that eye-roller, I'd like to just say: That's exactly what I'm saying.

Yes. I know that "what is popular isn't always right," but when it comes to the definition of science fiction, there's not really a moral imperative here. Culture changes the way we use language, irrespective of whether or not people like that change. Old-guard literary SF people don't have to like the new, more broad definition of science fiction, but they do have to live with it.

When George Lucas says "Star Wars isn't a science fiction film," he's really saying, "Star Wars isn't really a science fiction film according to definitions of SF from before 1977." Think about it. George Lucas isn't going to sit there and say, "I redefined the way people define science fiction." Even though that's exactly what he did.

Is science fiction a real genre?

Luke doesn't care if you call him sci-fi or not.

The reason why the debate about "what is science fiction" gets geeks all riled-up is mostly because the conversation is a trap. Unlike a mystery or a romance, science fiction doesn't have story-telling rules. Instead, sci-fi can encompass all the narrative genres. Shows like Star Trek or Doctor Who can do horror, comedy, romance, and mystery, all with the same characters in the same setting.

The reason why people refer to Star Wars as "space fantasy" or "space opera," is those genres have more definable rules. And I'll give them that! Star Wars might be space fantasy or space opera. But its setting is still a science fiction setting.

The world of Star Wars has science-fictional devices and technology that allows the story to take place. True, the stories are not about technology, but that hardly changes the presence of a lightsaber, droids, or hyperdrive. The status-quo of Star Wars lives in a science fiction universe. Meaning that yes, by default, Star Wars is science fiction. And until the real-world advances to the point where starships, robots, and laser guns are not science fiction elements, it's going to stay that way.

This article was originally published on