Building the World of Fallout

Production designer Howard Cummings and costume designer Amy Westcott reveal how they brought the universe of Fallout to the screen.

“How did they ever make a movie of Lolita?” This is the now-famous tagline of Stanley Kubrick’s 1962 film. Although the tagline was, of course, referring to the controversial subject matter of Vladimir Nabokov’s book, the same words could just as easily be applied to Amazon’s ambitious new video game adaptation: How did they ever make a TV series of Fallout?

Although the world of Fallout may not be controversial, it is infinitely vast and, as such, practically unadaptable. Evolving over the course of nine games and more than two decades, Fallout sets the scene in a retro-futuristic world in which 1950s social traditions have persevered while atomic energy simultaneously spurred the development of ultra-advanced technology. By the 2070s, suburbanites are living the white picket fence, nuclear family American dream — with the helpful addition of robots and some very cool jet-cars. Then, the apocalypse happens. Atom bombs drop across the country, and the wealthy scurry underground into bunker-style subterranean communities known as Vaults, built pre-emptively by the corporation Vault-Tec. The games are largely set a few hundred years down the line as various Vault dwellers emerge to the surface to find a Wasteland where social order and infrastructure have all but collapsed.

“Westworld was all black, white, gray, and red, and this was all color.”

Amazon’s show, spearheaded by showrunners Geneva Robertson-Dworet and Graham Wagner and directed by Westworld’s Jonathan Nolan (at least for the first three episodes), introduces us to a brand new cast of characters and story arc set within the sprawling Fallout universe. It’s 2296, 219 years after the nuclear apocalypse and the furthest into the future the franchise has ever taken us. Lucy (Ella Purnell) is living a cozy, comfortable life safe in the confines of Vault 33, until raiders break into her Vault and kidnap her father, Overseer Hank MacLean (Kyle MacLachlan). So Lucy leaves the safety of the Vault behind to search for him in the Wasteland above. There, she meets a colorful cast of characters, among them: Maximus (Aaron Moten), a trainee Knight in the Brotherhood of Steel; and the Ghoul (Walton Goggins), a gunslinging, noseless mutant who has been kept (barely) alive since the apocalypse.

Though this may be an entirely new saga, there is no question that it is set within the all-too recognizable world of the Fallout series. In fact, Nolan was committed to bringing this vast universe to life as faithfully and precisely as possible — and this daunting task fell on the shoulders of production designer Howard Cummings and costume designer Amy Westcott.

“Graham and Geneva, the showrunners, just really nailed the spirit of the game — that dark, satirical humor,” Cummings tells Inverse, recalling the first time he read the script. “It was great to read something post-apocalyptic that was actually not so self-serious.”

Ella Purnell and Executive Producer and Director Jonathan Nolan on the set of Fallout.

It was a far-cry from the grave tone of his previous project with Nolan: Westworld.

“You know, Westworld was all black, white, gray, and red, and this was all color,” Cummings continues. “I told [Nolan], ‘The script is really close to the game — I think we should do the game instead of trying to make it a slicker, edgier version.’ And he said, ‘That’s what we’re going to do.’”

And so, Cummings and Westcott dove into the vast world of Fallout. Neither being self-proclaimed “gamers,” this involved a mountain of research.

“A lot of the job is getting into the world,” Westcott tells Inverse. “There’s a great book that we all used for reference based on all the art from Fallout, but we also spoke to people who were very familiar with the game and who knew not only the playing of it and the ins and outs of the game but also the rules because there are a lot of rules within each different world that we had to adhere to.”

Cummings attempted to play the game himself, but when he got stuck, he turned to YouTube. “You can go online and there’s this stuff that people have spent hours editing and putting together,” he says. “I learned the game by looking at what the fans did with it — by watching them playing it. And the more I looked at it, the more and more I liked it.”

“I knew that fans would sit there and go through it all and find every friggin’ Easter egg!”

The more he watched and listened to the fans, the more detail he discovered within the universe. “It all has such history. It’s crazy — I used to turn on my phone and just fall asleep listening to the history of Fallout.”

Cummings became so familiar with the look and feel of Fallout that Bethesda Games, the company responsible for the series, essentially “let [him] go” do his thing, he says. “But I had to go to them when we were creating new stuff, because I wanted to make sure it was right. I knew that fans would sit there and go through it all and find every friggin’ Easter egg!”

Bethesda collaborated with Cummings, helping him craft many new crucial pieces of Fallout lore — perhaps most excitingly, a map showing the locations of every single Vault in America. It is this mixture of ultra precise replication paired with thoughtful new creation that makes the design of the series a feat in world-building and a surefire hit with fans and newcomers alike.

Vault Dwellers

The Vaults were painstakingly recreated from the video games, to make the show feel as immersive as possible.

Lucy’s journey begins within the subterranean paradise of Vault 33. For fans of the franchise, her home will be instantly recognizable — practically everything is a detailed re-creation of the Vaults seen in the games.

“We were tying our look mostly to Fallout 4, but I stole things from Fallout 76 and Fallout New Vegas. I stole whatever I could even from the early things,” Cummings says.

The spherical blue and yellow concrete tunnels are stained with old watermarks and bedecked with cheery Vault Boy posters complete with can-do motivational statements. Each little bunker is charmingly decorated with the cookie-cutter trimmings of ’50s suburbia — a fake lawn, a mailbox, a lawn chair. The doors are sealed with retro gear mechanics. Even the gray crates on the floor are almost exact replicas of those found in the games.

“We matched the Vaults — every little detail,” Cummings says. “I said, ‘OK, I’ve got to nail those.’ And it was so detailed. I’ve done Victorian houses that had less detail involved, which is crazy.”

Cummings had the same meticulous approach when it came to iconic locations from the game’s universe. He brought truckloads of sand to Staten Island while recreating a Super Duper Mart, transforming an abandoned supermarket into such a realistic post-apocalyptic set that local fans “tried to break into the place” in their excitement. He also brought to life the famous Red Rocket gas station with scrupulous accuracy.

“[The Vault] was so detailed. I’ve done Victorian houses that had less detail involved, which is crazy.”

“It actually wasn’t in the script, and I begged the showrunners to put it in because I loved the design of it so much,” he says.

But layered within Cummings’ exact rendering of the Vaults of the games, there are also delightful little details that serve as new additions to the pre-existing world. Adding to the iconic, tongue-in-cheek ’50s-style brand names fans know and love (Nuka Cola, Radiation King) Cummings invented a few of his own. Lucy gets her head smashed into an Atomic Queen stove, for instance, and a three-dimensional moving image of a rural Nebraska skyline is projected onto the walls of the main communal area in the Vault by a Telesonic projector.

This moving skyline was one of the major new designs. It was created using a digital stage rather than a green screen. Ironically, this meant the artificiality of the Vault Dwellers world looked as realistic as possible. “The environment there was meant to look artificial,” he says. “We called it two and a half D instead of 3D, because it’s built in layers. During the fight, you can see some of the layers fall out as the film breaks up.”

Of course, bringing the iconic Fallout Vaults to life would not be possible without Westcott’s remarkably detailed Vault jumpsuits. “I needed to get them right to be respectful to the fans and to what the game creators made in the first place,” she says.

The Vault jumpsuits are as game-accurate as reality allows.

Transforming the iconic two-dimensional outfit into something three-dimensional meant understanding the outfit on a practical level. How was it used? What was each piece of the jumpsuit actually for? “The biometric pieces that you see — we had to find out what each piece was for. There’s that leather area where the Pip-Boy goes, for instance. And it was really important that the suits were 3D, living, breathing, working costumes — they had to stretch in every way possible and then come right back to their original state.”

The only other costume we see in Vault 33 is Lucy’s wedding dress, a gown that has been recycled for every Vault 33 wedding throughout its history and another inventive addition to Fallout’s pre-existing lore. “The idea behind the dress was that it was passed down from generation to generation in the Vault because it was the only wedding dress. So, it had to have that retro-futuristic ’50s feeling to it,” Westcott says.

Scale & Size

Lucy (Ella Purnell) leaves the world of Vault 33 to explore the surface world.

Once Lucy leaves her sheltered Vault life behind and enters the big, bad world of the Wasteland, Cummings and Nolan knew that depicting the sheer enormity of the barren landscape was essential.

“In Westworld, we used places like Utah to make the park feel bigger,” Cummings says. Nolan wanted to do something similar with Fallout “to make it more epic.” For expansive shots of the barren Wasteland, they shot in Namibia in Southern Africa. This use of real locations rather than special effects once again helped create the impression of real space. “When Lucy comes out of the Vault, the Santa Monica Pier Ferris wheel [is CG], but most of what you see is actually there,” he says.

“It was just swallowed up by sand. It was so spectacular.”

They also used Kolmanskop, a “crazy town” in Namibia that was abandoned sometime in the ’40s for the scenes in which Lucy explores abandoned homes near the entrance to her Vault. “It was just swallowed up by sand. It was so spectacular, and [Nolan] and I had been talking about [shooting something there] for about five years,” Cummings says. With the peeling paint on the walls and eerie mountains of sand covering the floors, the town was the perfect real-life location for depicting the derelict, crumbling homes that are a common feature of the game's open world.

Brothers of Steel

The Power Suit in Fallout.

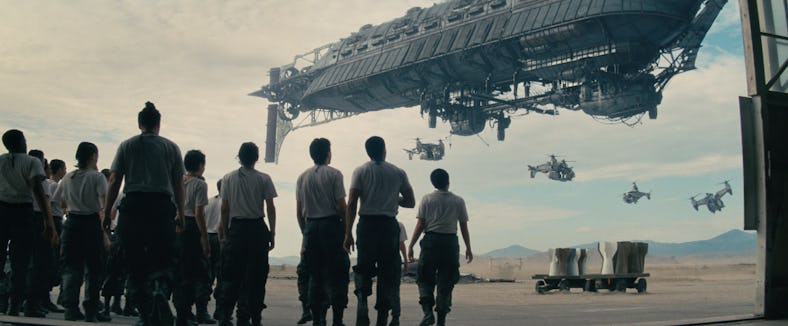

Within Fallout’s vast world, we also meet Maximus, a trainee in a military order of knights run by zealous monklike leaders known as the Brotherhood of Steel. Maximus dreams of one day becoming a knight and donning the famous steel Power Armor suit — he gets to step into the iconic armor a little sooner than expected after his knight is killed by an irradiated bear.

Remarkably, in its dedication to making everything as real as possible, the design team endeavored to actually create this suit of armor that has become synonymous with the Fallout series.

“They wanted the armor to be real, not CG,” Cummings says, explaining that on most projects, this kind of suit would likely be created using a mixture of costume and special effect. The team enlisted the help of Legacy, the company behind Iron Man’s suit. It took about 18 months to craft the costume, the first of its kind, with functioning hinges, ventilation, and mobility.

“I think this was one of their most complete set pieces of armor,” he says. “And it really did make a big difference. You can see the attitude and the acting in it — that all translates because it’s not CG.”

Much attention was paid to the Brotherhood of Steel and its armor.

This project was a big one. Not only did the team create a suit for Maximus; it also had to create other suits for other knights and for the stunt doubles. Plus, they needed a special suit made that would open and show the inner mechanisms as seen in the game universe. They even had to build a special giant chair so that Moten could sit down in between takes without removing the armor.

The Ghoul

Walton Goggins’ The Ghoul has become the show’s breakout character, and his distinct look has helped a lot.

And then there’s the Ghoul. Like the Vault Dwellers and the Brothers of Steel, unsettling human mutants are vital figures in the Fallout universe.

The Ghoul, we eventually discover, is in fact Cooper Howard, a pre-War actor kept alive for hundreds of years after being exposed to the nuclear blast that destroyed the world. In the centuries since, he’s developed a masochistic appetite.

“Walton is, like, the coolest guy on Earth — he’s like the original Marlboro Man.”

“[We were influenced by] Clint Eastwood-style Westerns — at the center they had this extreme badass,” says Westcott. “That had to be our goal — he had to be so much cooler than everybody else. Of course, Walton is, like, the coolest guy on Earth — he’s like the original Marlboro Man.”

The Ghoul’s look has already become iconic.

To create his look, which has already become iconic despite having no previous history in the games, she aged his pre-fallout cowboy shirt 300 years. “Then we added the Duster, which we just shredded the hell out of at the bottom, so it was almost ghostly in the wind,” she says. “He becomes this specter. Then we put gunshot holes and things like it had to look like it had been through something.”

Hinting at a hidden meaning in his costume, Westcott teases carefully, “We deeply shrouded the Ghoul character in the scorpion insignia. There’s a Scorpion embedded in the amber of his belt buckle.”

Rebuilding Civilization

Lucy (Ella Purnell) exploring a dilapidated house on the surface.

The world of the show continues to expand as Lucy ventures to Filly, a town built within a scrapyard on the outskirts of what once was Santa Monica.

The town is drawn from similar habitats that exist in the world of the game. “That kind of settlement made from scrap appears in the game a couple of times,” says Cummings. “Megaton City [from Fallout 3] is one of them.”

Filly is a miraculous feat of design, a junkyard piled high with layer upon layer of metal and trash (including a bus and bits of an old plane, teetering atop a pile of scrap). Decorated with ancient repurposed street signs, it’s a place where people come to trade and hunt for junk.

“The decorator on the show, Regina Graves, she got all that scrap and junk,” says Cummings, “the door and windows and a lot of the rusted sidings.” Even the jet parts were shipped in from an “airplane graveyard” in Lancaster.

“Todd, who is basically Mr. Fallout, came to the sets, and he put his hand on the tunnel of the Vault and he said, ‘I’m in the game.’”

Cummings extended the town by shooting its outskirts in a real car junkyard in New Jersey. “It’s the Grand Canyon of junk. It’s unbelievable,” he says of the location. “Those cars from the ’40s were put there, and the forest grew up around them.”

This inventive set is brought to life by the people who inhabit it — a fascinatingly colorful cast of extras dressed in wildly inventive mishmash outfits. One woman wears a woven basket on her head; another dons an old metal mixing bowl.

“It’s all about what you find and you scrounge and you trade — you get your pieces through living,” says Westcott of designing these bizarre outfits. “They just Frankenstein together whatever they can find to make something functional and covering, because it’s sunny and dusty and brutal out there.”

She adds, “My team and I ravaged every flea market, every trash can, every estate sale trying to find these really individual things, and then we recreated them into little wearable pieces of art.”

The costumes of the Wastelands are cobbled together via flea markets, estate sales, and even garbage.

As the show progresses, we see more and more of the Wasteland. Cummings is particularly proud of the radio station surrounded by bizarre booby traps. He also loves the Season 1 final climax, shot in the Griffith Observatory.

“It looks like some crazy absurdist play. I always wanted to do an opera set, and this is my opera,” he says. “In the end, it is actually so dramatic. They could be singing the dialogue, what’s happening is so cataclysmic.” He built the larger-than-life set to match.

Prime’s Fallout has already stunned fans with its realistic, precise rendering of the game’s universe. But the team’s accomplishment goes beyond simply creating sets and costumes that look great on the small screen — their creations quite literally brought the world of the games to life. “I used to love to watch actors come on to the sets because their mouths would fall open — and then they would just get into it,” says Cummings.

And for those who have invested their lives in creating the Fallout universe, such as Bethesda director Todd Howard, it’s been nothing short of magical.

“Todd, who is basically Mr. Fallout, came to the sets,” recalls Cummings, “and he put his hand on the tunnel of the Vault and he said, ‘I’m in the game.’ Probably the best compliment I could get.”