The best Harry Potter movie is finally streaming on HBO Max

While the series as a whole is great, one film stands above the rest while setting the tone for everything that came after.

Some art needs no introduction. Whether you are a fan, were a fan, or never gave it the time of day, sometimes you just know what a thing is about. You might never have seen Star Wars, but you know it involves space battles and laser swords. Even if you’ve never read a Batman comic, you know it centers on a costumed superhero who fights crime in a dark city.

Then, there’s Harry Potter. A millennial touchstone as both a globally best-selling book series and Hollywood film franchise, Harry Potter instilled a love of literature in generations of children with its simple premise, complex narrative, and a richly textured world that remains unparalleled in modern popular culture.

A Harry Potter cosplay meetup at Comic-Con 2018 in San Diego.

While author J.K. Rowling has expressed horrifically regressive views on trans people, we can take comfort knowing Rowling wasn’t involved in everything that made the story of Harry Potter special.

Though Rowling penned every book and faithfully adapted them into a film series that grossed $7 billion between 2001 and 2011, she didn’t make every creative decision along the way. She didn’t cast the actors, build the sets, set up lenses, sew the costumes, compose the music, or edit the films together. Primarily an advisor and producer on only the last two movies (both parts of Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows), Rowling was involved only up to a point.

And it’s with that comfortable distance that we can say the Harry Potter films are still quite good as the movies finally become available once again on HBO Max (they were available at launch, but quickly disappeared due to complex licensing deals). However, one in particular stands head-and-shoulders above the others: Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban, from 2004.

Across all eight movies, four separate directors — Chris Columbus, Alfonso Cuarón, Mike Newell, and David Yates — brought something unique to the table. This wasn’t originally supposed to happen.

Columbus, whose biggest film before Harry Potter was 1990’s Home Alone, was slated to direct seven films in the series (before the decision was made to split Deathly Hallows into a two-parter). But on the basis that Columbus would miss his family growing up if he committed to 10 years of movie-making, the filmmaker left after 2002’s Chamber of Secrets. That’s when Warner Bros. hired Mexican director Alfonso Cuarón to helm Prisoner of Azkaban, arguably the creative zenith of the Potter films that also represented a tonal turning point for the franchise. Cuarón, not Columbus, was the first to direct an entry in the series that wrestled intently with the entire saga’s coming-of-age journey.

Years before Disney-owned Marvel plucked indie filmmakers like Taika Waititi and Chloé Zhao to play in their multi-billion-dollar toy box, Harry Potter established a prototype for that pipeline by hiring Cuarón. (It should be said that the director was also not the studio’s first choice, instead being selected after Kenneth Branagh and Guillermo del Toro passed on the job.)

Alfonso Cuaron (left) with the cast of Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban.

Cuarón was no stranger to Hollywood, with pictures like 1995’s A Little Princess and 1998’s Great Expectations in his rearview, but he was quickly becoming an adult-oriented auteur who didn’t easily fit in the family blockbuster space. Although A Little Princess was an acclaimed family film, 2001’s explicitly erotic Y tu mamá también set Cuarón on a more mature path that later included Children of Men (2006), Gravity (2013), and Roma (2018); all gripping pictures firmly not for children.

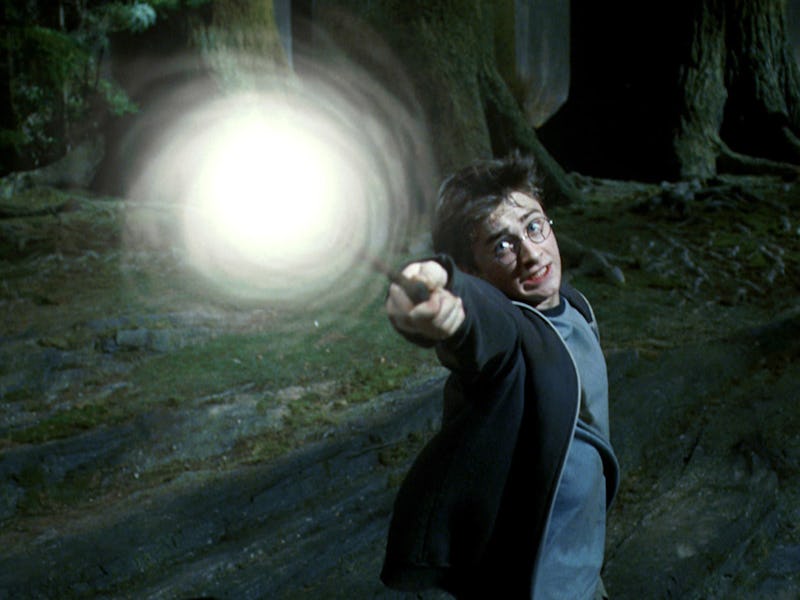

But, miraculously, Cuarón’s filmography also includes Prisoner of Azkaban, a compelling detour for both the director and the Potter series that primarily explores the growing pains of one boy wizard and his friends. In Prisoner of Azkaban, a rogue magician named Sirius Black (Gary Oldman) escapes a wizard-world prison and threatens to kill Harry Potter (Daniel Radcliffe) — or so everyone thinks. This story’s resolution matters less than how Cuarón tells it.

Shifting away from Columbus’ static cameras and pristine design (which had been ideal for Potter’s first two years at Hogwarts), Cuarón saw value in creating something more free-flowing and messy. Along with the constantly moving camera that would become a Cuarón specialty (see: Children of Men and Gravity), he encouraged all the actors playing students to dress themselves, straying from their previously uniformed looks.

“What I really wanted to do was to make Hogwarts more contemporary and a little more naturalistic,” Cuarón says in the film’s production notes. “I studied English schools and watched the way the kids wore their uniforms. No two were alike. Each teenager’s individuality was reflected in the way they wore their uniform. So I asked all the kids in the film to wear their uniforms as they would if their parents weren’t around.”

Prisoner of Azkaban was the first film to let the characters break free from their stiff Hogwarts uniforms.

Cuarón’s film brings a touch of authenticity to this world of magic. The comparatively darker story of Prisoner of Azkaban, with its focus on an adult criminal trying to kill a young boy, is the first real step into adulthood for Harry. For the first time in Harry Potter, magic feels dangerous and capable of great evil. It’s not just wands and witches in pointy hats. There’s purpose and variety to the magic of this film, like a hammer that can be used to either build a home or bash in a skull. This conflict is felt throughout Prisoner of Azkaban, as magic manifests in both colorful candy stores and chilly train rides with Dementors.

An unmistakably hormonal energy also runs throughout Prisoner of Azkaban, with the three main characters — Harry, Ron, and Hermoine — physically touching and reaching for each other at critical moments. They appear constantly in unkempt Hogwarts uniforms and/or Muggle clothing that can make them disappear into a crowd at a shopping mall. Cuarón’s floating camera establishes a lack of safety and purchase in this increasingly dangerous world, one the director and cinematographer Michael Seresin paint with colder, more muted colors than the warm tones of Sorcerer’s Stone and Chamber of Secrets.

Snape’s character becomes significantly more complex in this chapter of the Harry Potter saga.

Prisoner of Azkaban was the only Harry Potter film Cuarón directed. Mike Newell succeeded him on 2005’s Goblet of Fire, which emulated Cuarón’s visual stylings but added more studio polish. By the time David Yates took over for the last stretch of the series (starting with 2007’s Order of the Phoenix), it was clear Cuarón laid a foundation for the series to flourish into continued critical and commercial success.

Like Fast & Furious and the MCU, Harry Potter is a film series that was allowed to grow and change with time, discovering what worked best to bring its wizarding world from the page to the screen.

All eight Harry Potter films are streaming on HBO Max in the U.S. starting June 1.

This article was originally published on