John Carpenter’s First Sci-Fi Movie Proved What He Was Capable Of

Carpenter’s “Spaced Out Odyssey” is primitive, but all the building blocks of a legendary career are here.

Few filmmakers are better at undermining our sense of social order than John Carpenter. Halloween turned suburban backyards into shadowy nightmares, The Thing twisted masculine bonds into warped paranoia, and They Live pulled the rug out from under the ideals of American capitalism. He’s been toying with these themes his entire career, but what’s surprising about Carpenter’s debut film is the genre where he found his footing.

Dark Star’s credits reveal a wealth of future talent. Carpenter is the director, and the film’s co-writer and co-star is Dan O’Bannon, who would later write Alien and have a hand in blockbusters like Total Recall. Nick Castle, who would play Michael Myers in Carpenter’s upcoming Halloween and then launch a directing career himself, shows up as a goofy beach ball-shaped alien.

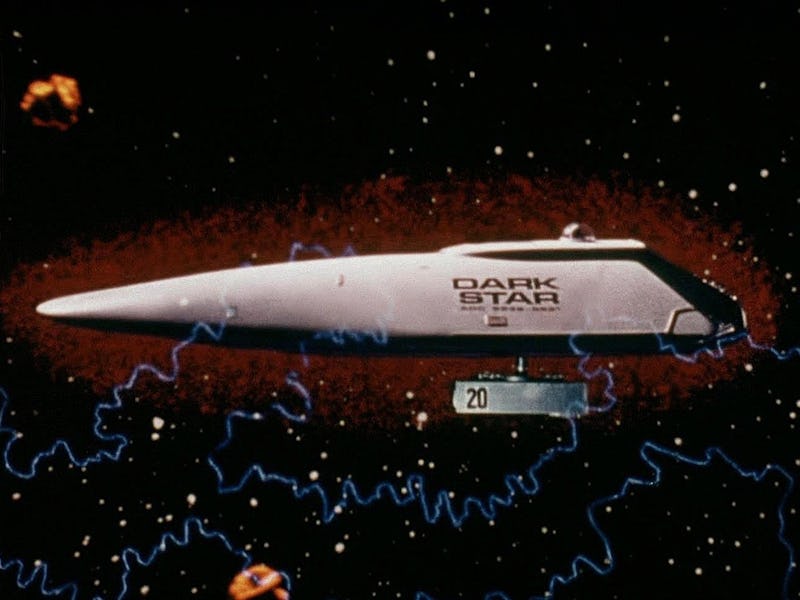

Wait, beach ball? Yes, Dark Star is far from the adventure and horror elements that would make Carpenter famous. Instead, it’s a sci-fi comedy about the deeply bored crew of the Dark Star, a spaceship meant to seek out dangerous planets that might present problems for human colonists. By the time Dark Star begins, though, their mission has devolved into an existential haze, and the men aboard have let go of their collective sanity.

Creating a sci-fi comedy in the early ’70s wasn’t exactly Carpenter’s plan; Dark Star had begun as a student film when Carpenter studied at the University of Southern California, and only later became a full-length movie. Production lasted several years, with Carpenter trimming and adding and reshooting until it was eventually released to a middling response. Carpenter’s status as a household name would have to wait, and Dark Star would have to go through a few rounds of critical reappraisal before people began to find its worth.

While the film is extremely roughshod in places, it is a promising start, and 1974 was an opportune time for a sci-fi comedy that poked fun at the self-serious ambition of the genre. Still basking in the revolutionary impact of 2001: A Space Odyssey, theaters were now flush with titles like The Andromeda Strain, The Omega Man, THX 1138, Solaris, and Soylent Green. Many of these titles portrayed a haunting future in which mankind would be forced to grapple with advanced technology while society fell apart. Dark Star operated on the same wavelength at a microscopic level, using the ship’s small crew to illustrate the malaise of dystopian ambition.

It may look like any other sci-fi, but these people have no idea what they’re doing.

It also provided commentary on what seemed like a dying breed of counterculture. The main character, Lieutenant Doolittle, is a former surfer and hippie now forced into a command role. To say that he’s unequipped is an understatement, and he makes for an odd reflection of the dreamy, optimistic progressivism of the ’60s that had soured under the harsh glare of Vietnam, economic crises, and political cynicism. When faced with a bomb threat, Doolittle’s plan is to teach the bomb philosophy. When that fails and the ship explodes, Doolittle grabs a piece of debris and surfs on it, nabbing his last chance at escapist freedom before the universe snuffs him out.

Despite their casual ineptitude, it feels like Carpenter has compassion for the doomed crew of the Dark Star. They’re treated not as pure jokes, but as comical iconoclasts. It’s a character type that would show up over and over again in his work (usually in more serious fashion), from Snake Plissken in Escape from New York to the drifter Nada in They Live. All are men who understand that, whether it’s the state or the rich in charge, they feed us nonsense.

Dark Star is about a society with more scientific power than it knows what to do with, but not enough empathy to ensure that its use of its fancy tools is worthwhile. When Doolittle gleefully rides away from the Dark Star’s wreckage, it’s his last act of rebellion against a world that didn’t really care how long he stayed in space.

There are certainly worse ways to go.

Carpenter’s next film, Assault On Precinct 13, would go a long way toward establishing his visual style, and Halloween would propel his name into the pantheon of horror directors. He’d also co-write Eyes of Laura Mars, and direct Someone’s Watching Me! for television, both arguably better than Dark Star.

But Dark Star remains a fantastic look at the structures (or lack thereof) that rule Carpenter’s worlds. They are all places we think we know, from our neighborhoods to the far future. But just a peek under the surface will cause them to unravel, revealing horrors and lunacy beyond our comprehension. “You are not where you think you are,” they tell us. “You are not going where you think you’re going. You are not safe.”