One Sci-Fi Movie Series Invented Star Wars, Captain America, and Everything Else

George Lucas owes nearly everything to Buster Crabbe.

Paradoxically, nostalgia is always changing. Today, the Star Wars franchise may seem like it endlessly recycles beats and character moments from older stories, but the specific things people are nostalgic for have fluctuated. For example, everyone loves Hayden Christensen now. But, when you take a larger view of the Force, you may wonder what George Lucas was nostalgic for in the first place. In 1977, critics and science fiction aficionados were well aware that the original Star Wars was deeply rooted in nostalgia. In her 1978 review of Star Wars, Ursula K. Le Guin bemoaned, “What is nostalgia doing in a science fiction movie?” Obviously, the original Star Wars wasn’t nostalgic for itself. So what kinds of nostalgia was it?

The short answer is Buck Rogers, a 12-part movie serial that debuted on February 2, 1939. Although Flash Gordon heavily influenced Lucas as well, historically, the character of Flash only exists because Buck came first. And, when you revisit the 1939 Buck Rogers, you’ll find the aesthetics very similar to not just the classic Star Wars trilogy, but most notably, The Phantom Menace.

Buck Rogers origin, explained

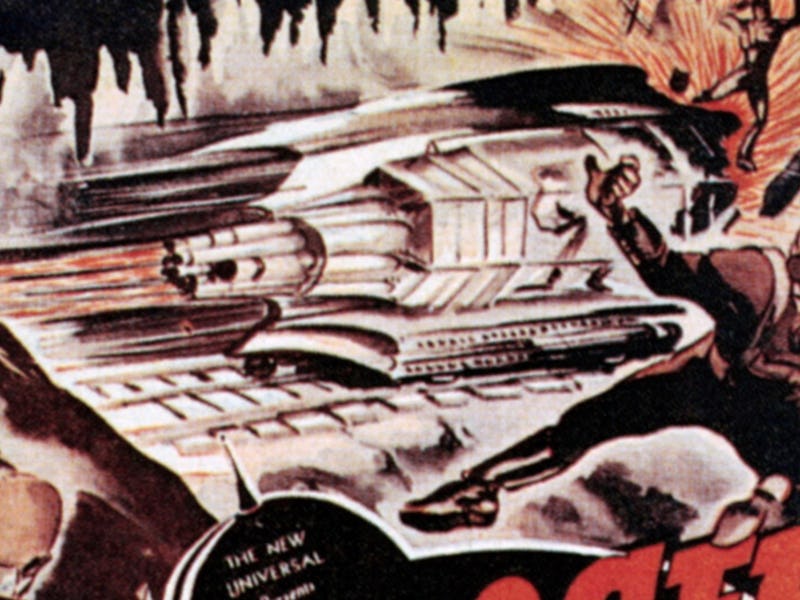

A 1939 poster for Buck Rogers.

By the time Buster Crabbe played Buck Rogers in 1939, the character had already existed in a few different iterations. William Francis Nowlan created “Anthony Rogers,” for his 1928 novella Armageddon 2419 AD. Like most Buck Rogers origin stories, the tale begins with a contemporary man named Rogers, who is accidentally put in suspended animation and wakes up in the 25th century. In the novella, most of the action takes place on Earth, but by 1929, the character was reborn as a daily comic-strip character and more space opera action began. Of note to fans of Steve Rogers — aka Captain America — Buck Rogers predates Cap by 11 years. Plus, the idea of Steve Rogers getting frozen in ice, and therefore, emerging in the modern day, was implemented by Marvel in 1964, 35 years after basically the same thing happened to Buck Rogers.

The Buck Rogers comic strip ran from until 1967, but the success of the strip created Buck’s biggest sci-fi action-hero rival, Flash Gordon. While Buck was published by the National Newspaper Syndicate, a competing comic strip brand, King Features Syndicate, created Flash Gordon as an answer to Buck. Interestingly, King Features originally wanted to do a comic strip adaptation of John Carter, the displaced Earth hero who ends up on Mars in the novels of Edgar Rice Burroughs. But because Burroughs didn’t sell the rights, King Features created Flash, a totally new character, who nearly eclipsed the popularity of Buck. Funnily enough, history would repeat itself in the early 1970s; George Lucas couldn’t get the rights to Flash Gordon or Buck Rogers, so he made Star Wars instead.

The Buck Rogers movie stole back from Flash Gordon

Buster Crabbe as Flash Gordon, the OTHER big space hero, and Buck Rogers rival. Luckily, Buster played both of them.

Confusingly, although Buck predates Flash in the comic strips, the reverse is true with the film serials; Flash came first. In 1936, a 13-part Flash Gordon serial ran in theaters, three years before the Buck Rogers serial hit in 1939. And here’s where it gets even more confusing: The actor who played Flash Gordon in 1936 was the same guy who played Buck Rogers in 1939 — Larry “Buster” Crabbe. (This is a little like Chris Evans starring in The Fantastic Four before Captain America, but not quite.)

Generally speaking, the overall plot of Buck Rogers is slightly more concerned with science fiction, and a little less fantasy. Though, overall, both fall into the subgenre that some critics derisively refer to as “space opera.” In the 1993 Encyclopedia of Science Fiction, John Clute and Peter Nicholls write that Buck Rogers is “not as lavish or baroque as the first Flash Gordon.”

But in terms of specific plot points and various aesthetics, Buck Rogers feels closer to George Lucas’ vision for the Star Wars prequels. After Buck and Buddy awaken from their 500-year slumber, there’s suddenly a blockade that needs to be run, and some allies contacted on a neighboring planet. The viewscreens that everyone uses to communicate with the villain, Killer Kane, warble and swirl distinctively, which yes, is basically the identical effect from The Phantom Menace when Queen Amidala contacts the Trade Federation.

The sleeper will never awaken

George Lucas would have done these costumes exactly if he could have.

Interestingly, the one thing that George Lucas never bothered lifting from Buck Rogers (or Flash Gordon or John Carter) was the fish-out-of-water idea of bringing a contemporary man into a space opera adventure. In all versions of Buck’s story, he’s a person from the 20th century, fighting for the good guys in the 25th. This device is, of course, common in science fiction, but in has mostly fallen out of fashion after Star Wars. From novels to films to TV, most space fantasy, or science fiction with a space opera angle, simply drops the audience into that universe, without an accidental time-traveling audience surrogate. Sure, Doctor Who tends to still have human companions from contemporary Earth, but that show lacks a constant future-tense setting and doesn’t really approach the space opera genre.

In other words, Buck Rogers set the standard, in many ways, for everything from Star Wars to Battlestar Galactica, all the way to Rebel Moon. But, it did so only with general plot points, and certain types of nomenclature. When you get granular and look at the characters more closely, the idea of a Buck Rogers — a human being from our time forced to live in another — is strangely less common. In this way, George Lucas took his nostalgia for Buck Rogers and turned it into something else. Setting aside the 1979 Buck Rogers TV remake (and the 1980 Flash Gordon movie), for the most part, space opera heroes after Buck no longer needed to sleep for 500 years before getting into the action. Buck may have invented a certain kind of genre, but once that genre evolved, nobody needed to bother waking Buck up from his eternal nap. The Skywalkers had taken over.