5 Years Past Blade Runner’s Dystopia, Is Cyberpunk Still Relevant?

On November 19, 2019 Rick Deckard got to work retiring replicants. Pop culture never moved on from that moment.

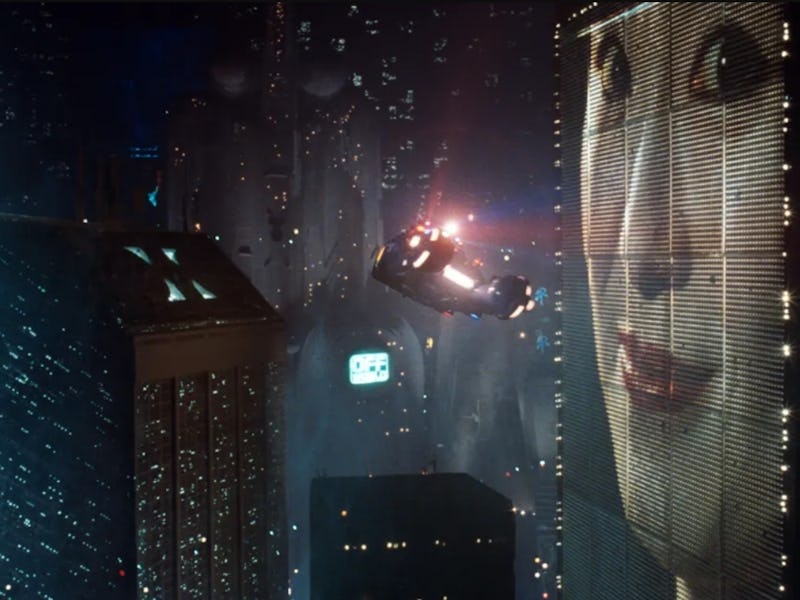

“Los Angeles November, 2019” is one of the simplest yet most effective title cards in sci-fi history. The sudden cut from plain white text to flying cars, belching pillars of fire, and endless city lights is an iconic opening that demonstrates just how far Blade Runner’s imagined future was from its 1982 release date.

In our 2019, blogger Jamie Zawinski realized that, thanks to a timestamp on archival footage in Blade Runner 2049, we can conclude that Blade Runner began on November 19th and ran through the 22nd. That means Rick Deckard got to work hunting and retiring rogue replicants five years ago today, and when we look at the current state of cyberpunk, it feels fitting that Blade Runner is fading into the past.

Ridley Scott’s vision of a dreary, rain-drenched Los Angeles remains as evocative as ever, and it still feels like you should be able to step into its overcrowded streets. But while obnoxiously huge ads and insidious corporations may be timeless sci-fi tropes, other elements are pure ‘80s noir. Deckard reads a newspaper and uses a payphone. Atari, Pan Am, and Bell Telephone are corporate titans. Androids are indistinguishable from human beings, but computer and TV monitors are bulky boxes.

Most notable is Blade Runner’s preoccupation with Asian imagery. By 1982, Japan’s economy was ascendant while American heavy industry struggled, prompting sci-fi as diverse as Blade Runner and Back to the Future Part II to play on fears that the trend would continue in perpetuity. In pop culture, Japan was exotic and powerful, while politically, the country became a sinister scapegoat; the same year Blade Runner came out, Chinese-American man Vincent Chen was fatally assaulted by two white men after they accosted him in a club and blamed him for their economic woes.

We can’t fault a movie made in 1982 for being from 1982, but Blade Runner is one of cyberpunk’s ur-texts, and the genre’s last five years have demonstrated a continuing inability to move beyond the rainy tech noir world it created. Cyberpunk 2077 — the cyberpunk phenomenon of the decade — is fun and gorgeous, but as a cyberpunk game it’s stuck in the 1988 of its Blade Runner-inspired tabletop source material.

Blade Runner inspired a generation of sci-fi, but visuals were often put before story.

Corporations are bad and punk is good, and that’s pretty much all Cyberpunk 2077 had to say. It’s a reasonable excuse to get into shootouts on the streets of Night City, but all the little worldbuilding details that made sense in ’88 — boxy monitors, cheesy slang, the continued existence of the Soviet Union, Japan eating our economic lunch — made it feel like a quaint throwback, retrofuturism for a generation of developers and fans who grew up worshipping Blade Runner. It’s hard to tell an intimate story about the dehumanizing nature of corporate omnipotence when you’re a huge development team working for an employer with a four-billion-dollar market cap, so it mostly focused on how cool samurai swords are.

A little silly escapism is fine, but mainstream cyberpunk has largely been reduced to aesthetics and nostalgia. Netflix’s Cyberpunk: Edgerunners had the same limitations as the game. The Matrix Resurrections was a movie about how The Matrix is now a quarter-century old, and Blade Runner 2049 also revolved around the legacy of its source material. Altered Carbon was so fixated on feeling cyberpunk that it set a fight to a song that references Blade Runner rather than tell a decent story. Even Space Marine 2 had to throw dozens of bulky CRT monitors displaying lines of green on black code everywhere because Warhammer’s vision of the distant future was conceived in 1987.

Blade Runner was based on a novel, and aside from a tedious need to abuse “punk” as a suffix, literary sci-fi and indie gaming have largely moved on from cyberpunk; see post-cyberpunk, biopunk, solarpunk, etc. But mainstream Hollywood and AAA gaming are loathe to look to the future. CD Projekt Red is working on a sequel to Cyberpunk 2077, while Apple TV is busy adapting William Gibson’s seminal 1984 novel, Neuromancer. Both will probably be fun, but it’s hard to imagine either having much to say. How do you comment on the present when you’re stuck in the past?

Admittedly, it’s a very cool-looking past.

Forty-two years after its release, Blade Runner remains as mesmerizing as its stark opening scene. But it’s not a story about how cool futuristic umbrellas look; all of its visual splendor is ultimately a backdrop for a story about what makes us human. That’s been forgotten or ignored by projects looking to use its imagery as marketing material, from Cyberpunk to reams of cheap novels aping its world and visuals. It’s telling that sci-fi creators with smarter insights into cyberpunk’s themes, like the small teams behind Citizen Sleeper and Umurangi Generation, have tweaked or abandoned the style rather than drag it into a future it no longer belongs to.

As a film, Blade Runner will forever be a towering accomplishment. But as its dreary future of 2019 disappears further and further into the past, it’s become an increasingly potent reminder that the genre it’s synonymous with has struggled to move beyond its greatest hits. It’s time to leave its aesthetic behind, no matter how moody it feels to watch Harrison Ford sip his Scotch and look out at the endless rain on a cold November night. After all, those moments don’t last.