32 years on, Akira’s cautionary tale of man’s downfall is a lesson to us all

And it's streaming for free online right now...

No matter how many times I watch it, I never fail to be in awe of Akira.

Originally born as an allegory for Japan’s traumatic relationship with nuclear power, Katsuhiro Otomo’s inimitable style and wonderfully weird narrative has (rightly) become a timeless classic. Cementing itself as a stylistic icon as revered as Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner, Akira’s influence can be felt in everything from video games to street culture. 32 years after its limited U.S. release on Christmas day, this cautionary tale of a dying planet has never felt more poignant.

While a bit of a head-scratcher on first viewing, under all its sci-fi weirdness this beloved classic has always been a parable about mankind's lust to control nature. Watching Akira in a half-empty theatre for a bit of escapism in the midst of a global pandemic (thanks to a brief UK re-release in October), this animated slice of dystopian escapism feels chillingly prescient.

Look past the cool bikes and iconic soundtrack, and the (prophetically) 2019-set Akira tells a tale of a world on the brink of collapse. In a year where our planet is reeling from the deadly consequences of mass animal agriculture and the threat of climate change looms, Otomo’s inimitable tale no longer feels like just entertainment, but like something we should be learning from.

For the uninitiated, let’s take a moment to explain the film’s plot. Adapted from the six-part 2000-page manga series of the same name, Otomo’s two-hour anime retelling unsurprisingly moves at an almost whiplash-inducing pace — so bear with me. Set 30 years after the events of World War 3, Akira depicts a city in crisis. Attempting to rebuild itself after the damage unleashed by the war, 2019’s Neo Tokyo finds itself locked in a constant power struggle. Fought over by capitalist dictators and religious zealots, and ravaged by teenage street gangs, the Tokyo audiences see is a city visibly falling apart at the seams. Unfortunately for its poor populace, things are about to get a whole lot worse.

Focusing on the exploits of a 15-year-old outlaw named Kaneda and his biker crew, this gang of disillusioned young offenders finds themselves helplessly trapped in a dying world. With little to occupy their time but girls, violence, and vandalism, their days are spent tearing up the streets and sticking it to rival gangs. Then one night, everything changes. Mid-turf war, Kaneda’s friend Tetsuo finds himself swerving into a mysterious boy with psychic powers, and is quickly whisked away to a military hospital. From then on, Akira swells into a complex, dizzying ride – and it’s here where this bleak dystopia becomes uncomfortably relevant.

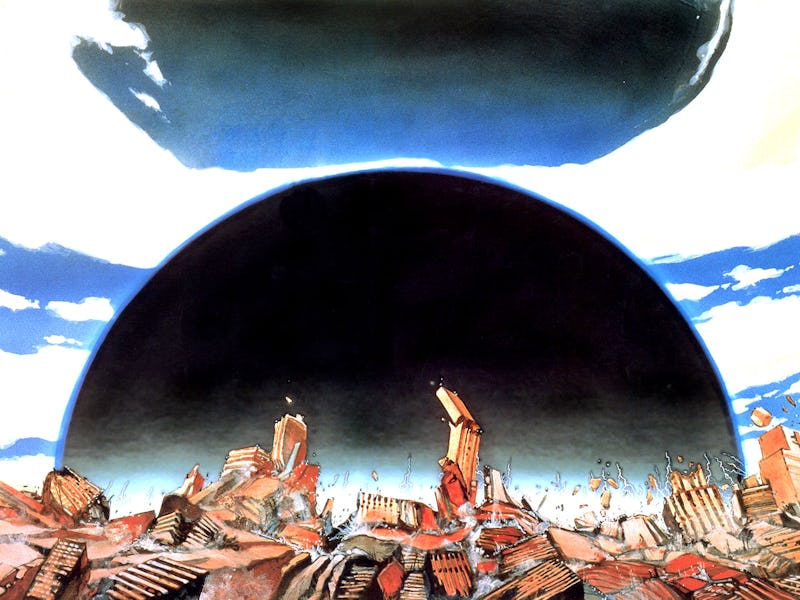

As military police enforce city-wide lockdowns and anti-government protests spill onto the streets (sound familiar?) it's revealed that Neo Tokyo’s government has been secretly experimenting on children in a bid to create super soldiers. During Tetsuo’s encounter with the mysterious psychic assailant – one of the aforementioned children - Tetsuo unexpectedly develops powers of his own. As these new psychic abilities mature at an alarming rate, thanks to a military scientist’s refusal to control Tetsuo, this once cowardly biker soon finds himself wielding the power of a god. Unable to control his new strength, in the film’s finale, Tetsuo’s unchecked energy manifests itself into an all-consuming black hole – eventually destroying Tetsuo and Neo Tokyo with him.

Tetsuo Shima in Akira.

So why does this fairly far-fetched film strike such a chord now? Back in 1988, Tetsuo’s arc was intended to symbolize two things: mankind’s irresponsible use of atomic power, and Japan’s rapid transformation from a nation crippled by 1945’s horrific bombings into a world-leading economy in the 1980s. In the years leading up to Akira, Western sci-fi flicks did their best to glamourize our increasingly tech-centric world, yet Japan’s harrowing relationship with technology had given them pause.

The questions Otomo raises in Akira then are two-fold: should mankind be scared, rather than in awe of this rapid advancement in technology? And, what is the true cost behind the world’s rapidly growing economies?

It seems like now, three decades later, we are finally getting our answers. In 2020, mankind can no longer ignore the very tangible cost behind our species’ alarmingly rapid advances. Just as the film’s rodent-like Doctor Onishi attempted to experiment on Tetsuo without considering the consequences, man’s decades of ravaging the Earth without heeding the warning signs have now ground life as we know it to a devastating halt.

Doctor Onishi.

While I intended to pop to the cinema for some much-needed escapism, Akira’s chilling message was too relevant to ignore. Take what happens in the city-leveling finale, for example. When Tetsuo’s power finally balloons out of his control, the visual language used to depict Tetsuo’s all-consuming corruption couldn’t be clearer. With Tetsuo’s mutating body unwillingly absorbing discarded scrap metal and electronics before ultimately swallowing him up entirely, it’s a clear warning that mankind’s flagrant disregard for the planet around us will end up ultimately consuming and destroying everything.

It’s hardly a one-off analogy in Akira either, with the sentiment actually summarised pretty nicely by Kaneda’s love interest, Kay while she’s being psychically possessed by one of those lab-made child psychics, Kiyoko. (Look, I did warn you that Akira’s second act was a lot.) As Kaneda struggles to come to terms with the shocking amount of power that Tetsuo now possesses, "Kay" attempts to explain with a fitting analogy:

“If an amoeba or any type of simple bacteria were to gain the power of a man, this bacteria would then appear as a god to its own kind. If the power of a human were to be explained to an amoeba, it would not do as humans do, but would merely harness this new power to do whatever an amoeba already does – consume and destroy”

While Kaneda stops audiences’ heads spinning with the brilliantly dense reply of “wait… you’re saying that Tetsuo is an amoeba?!” Kay’s allegory is a double whammy that hits pretty hard in 2020. With Tetsuo’s arc mirroring man’s lust to control power and our inability to overcome our own greed, this 32-year-old monologue now feels frighteningly apt. We find ourselves in a time where our species has devastated Earth’s once luscious Amazonian rainforests until what remains is largely wasteland. Where man’s unrelenting mass animal agriculture and its resulting putrid conditions helped spread the world-halting Covid-19 and prior that, its younger siblings, the avian and swine flu. And that’s before we even mention that in the last twelve months, both Australia and California’s temperatures have risen to such alarming rates, that these once idyllic landscapes fell victim to month-long raging infernos.

It’s little wonder that Akira strikes such a chord in 2020. Thanks to all our consumption and the ensuing destruction left in our wake, the once brilliant Homosapien is starting to sound a lot like Kay’s genocidal amoeba.

Violence in the streets during an earlier scene in Akira.

It’s all pretty bleak stuff, but mercifully, our prophetic anime doesn’t end without offering a glimmer of hope. After Tetsuo’s uncontrollable power swells into an explosion that wipes out (almost) all life in the city, Neo Tokyo is free to start again. With Otomo originally intending this ending to show how Japan could reclaim its cultural identity after rapid economic development had mutated it into something unrecognizable, the suggestion that we can use a terrible event to remold the world around us actually feels inspiring today.

Yes, Akira is a brilliant film, but like all art worth its weight in projector reels, it offers a point worth heeding. Maybe now we can use this forced global reset as our very own new dawn — an opportunity to rethink how we treat our planet and the people and creatures who reside within it.

Let’s hope our world leaders are watching Akira, then, but in the vast likelihood that they’re not, let’s strive to do what we can as individuals to usher in real change — before we bring about a Tetsuo-esque apocalypse of our own.

After a doomsday ending, Akira offers a glimmer of hope.