34 years ago, DC’s darkest Batman story redefined death for superheroes

In 1988, comic book fans murdered a 15-year-old boy.

Jason Todd was doomed from the beginning. Introduced as the second Robin in 1983 (by Gerry Conway and Don Newton), for the first three years of his life on the page he existed merely as a doppelganger of his predecessor, before the cosmic cataclysm of 1985’s Crisis on Infinite Earths untangled the convoluted web of the DC Multiverse and bound it into one metatextual story.

The streamlined logic wouldn’t last, of course. But many of the changes introduced after the reboot did. Jason’s backstory as yet another convenient circus orphan was erased in favor of turning him into an angry and sardonic street youth whose parents were stolen from him by the circumstances of Crime Alley.

Post-Crisis, Batman meets Jason when the kid is ambitiously trying to steal the wheels off of the Batmobile. Against his better judgment, Bruce offers Jason the chance to channel his worldly frustrations into the Robin mantle, a decision that set contemporary Batman readers ablaze with derision.

Jason’s attitude, his frequent skirting of Batman’s rigorous moral code, and an unfair, seemingly unconscious tendency to liken him to Dick Grayson caused a lot of fans to despise him. By the time editor Denny O’Neil decided to put the fate of the second Boy Wonder up to a popular vote in 1988, it seemed as if the universe itself had already demanded he would die.

Jason goes for the wheels in his 1983 comic book introduction.

The gruesome deed would happen in the storyline A Death in the Family. Scripted by Jim Starlin (creator of intergalactic despot Thanos) and illustrated by Jim Aparo, the groundbreaking miniseries drips with ghastly aura. Told over the course of four issues (Batman #426-429) from August to November 1988, each cover was penciled by then burgeoning talent Mike Mignola, his dense linework and rich shadows inspiring a growing sense of dread and macabre uncertainty.

Jim Aparo’s interior art uses bold colors to illustrate a globe-trotting adventure, in which Jason realizes not only that he is adopted, but that his birth mother is still alive and somewhere in the Middle East. Naturally, the melodramatic plot collides with Batman’s obsessive pursuit of the Joker, in heartbreaking fashion.

But beyond the spectacle of the story or the evocative quality of the art, A Death in the Family has remained a permanent fixture of comic book storytelling because it was one of the first times that comic book fans were handed control of the narrative in such a metatextual way. The result helped to legitimize a trend of sensationalist cynicism that would go on to pervade American comics for the following two decades.

Historically, it’s easy to see why there was so much appeal to the idea of giving fans control of a pop culture narrative. At the time, American readers were living in a country with a growing awareness of the seedy underbelly of U.S. foreign policy. Just two years prior, the Iran-Contra affair had exposed the Reagan Administration as the intermediary between a deal to sell weapons to the Islamist Khomeini theocracy of Iran. The plan was intended to serve as potential leverage in exchange for the American hostages being held in Lebanon at the time, as well as to fund America’s political interest in right-wing Nicaraguan militias. The Cold War had bred an American culture of paranoid cynicism throughout the ‘80s, and shades of the overall climate bled into comic book stories of the time, such as The Dark Knight Returns and Watchmen.

A 10th anniversary cover for Frank Miller’s The Dark Knight Returns.

A Death in the Family directly reflects pervading, ‘80s-era American attitudes towards the Middle East, and much of it has aged atrociously. Starlin kicks off the story with the Joker (who refers to himself as “just another victim of Reaganomics”) attempting to sell a nuclear warhead to vaguely defined Islamic terrorists in Lebanon, before taking it a step further and having Ayatollah Khomeini himself hire the Joker as the UN Ambassador to Iran. It is the culmination of an embarrassing series of storytelling gaffs that flattens the complexities of Middle Eastern turmoil into a homogenous caricature of racial stereotypes.

What the story lacks in geopolitical nuance, it makes up for in brutal spectacle. The sheer controversy surrounding those four issues transformed the very concept of death in comics. Sure, characters like Bucky, Gwen Stacy, and even Captain Marvel had met their ends within the panels of comic books before, but Jason’s demise was different: it was an event, heralded by an interactive gimmick stolen from Saturday Night Live and executed with a disturbing level of viscerality that previous comics rarely reached.

The image of the Joker gleefully battering Jason’s young body with a crowbar is carved into the collected subconscious of pop culture forever, and even though the story was met with immediate backlash, its ripples are felt today every time one of the Big Two announces a major hero death months in advance, or revels in cynical stunt crossovers like 2005’s needlessly grim Identity Crisis.

It’s a shame the more controversial elements of A Death in the Family have dominated the discussion of the storyline since its release because, at its core, it’s a deeply moving tragedy, one that highlights the crucial mistakes in Bruce’s relationship with Jason and juxtaposes them against the inevitability of his demise. Even though the mantle of Robin intensified Jason’s violent tendencies, it’s agonizing to watch Bruce and Jason start to truly connect with each other over the course of their journey, knowing it can’t last.

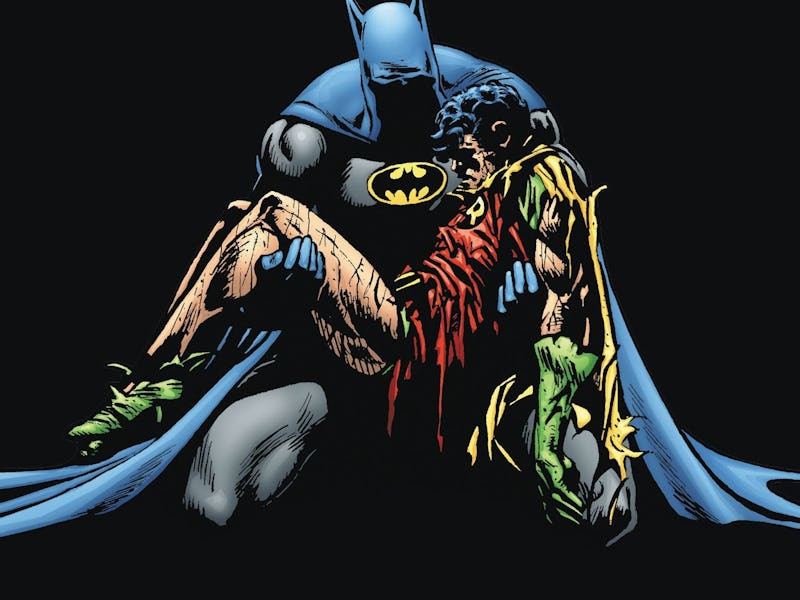

When Jason finally reconciles with his birth mother, Aparo gives us a close-up of an alarm clock, 15 pages before we get close-ups of the clock on the bomb that will claim Jason’s life. By the time Jason dies in Bruce’s arms, the book is inviting you to grieve for the potentiality of what could have been.

Mean-spirited, cruel, and controversial, A Death in the Family forever pushed the envelope of comic book storytelling, for better or worse. But alongside popularizing sensationalist gimmicks, it also redefined the status quo of the Batman mythos for years to come. Because of the death of Jason Todd, Batman was once again solidified as the tortured avenger, a solitary and tragic creature of the night.

As a result, the Caped Crusader’s identity in wider pop culture has often been reduced to a refusal to open up to others in fear of what will happen to them — a stubborn trope that has followed superheroes into the golden age of comic book adaptation. However, this has never been Batman’s whole story: Tim Drake, the third Robin, made his debut a mere year after Jason’s death, in a storyline that highlighted the importance of Batman having a Robin.

And what of Jason? 16 years after his death, he was resurrected by Judd Winnick as the second Red Hood – a brutal, gun-toting vigilante whose lethal methods made him a stark enemy of his adopted family. Jason’s transition into an anti-hero carried the same cynical “event” status that defined his death: a controversial spectacle that fixated more on the shock of bringing the deceased Robin back as a stone-cold murderer than much else.

Even though the storyline in which Jason makes his return, Under the Hood, is now considered a contemporary classic by fans, it’s hard to ignore the fact that, for a long time, many of Jason’s successive appearances have also been marred by a juvenile “edgy” sensibility that seems to revel in the “cool factor” of Jason being a brutal killer.

In fact, it wasn’t until very recently that several Batman writers have slowly pushed Jason back into Gotham’s larger community, allowing him a path of healing that exposes to him the fundamental flaws in his methodology. Through his return to the Batfamily, as well as leading his own superhero team known as The Outlaws, Jason Todd has become a bit of a poster boy for the concept of the redemption arc. Not only has he pushed himself to reckon with his trauma and his own anger, but he’s also emphasized the good in characters who have never been given a chance to be seen as such, like classic Superman foe Bizarro.

The kids are alright in Batman: Wayne Family Adventures.

Even though the execution has never been perfect, Jason’s climb back into the light can be seen as an allegory for a recent upturn in comics in which writers and audiences have come to recognize the infestation of needless cynicism in the medium. Not only has Jason embraced the comfort of community, but Batman himself has shed the abrasive loner exterior that DC Comics had thrust upon him for decades in favor of a sprawling family of sidekicks and heroes that reflect a certain level of contemporary optimism.

34 years after comic book fans helped the Joker kill a Robin, Batman stories (and comics as a whole) have come full circle in accepting A Death in the Family as important canon while rejecting the cycle of narrative pessimism that it unintentionally created.