Few Cartoons Have Defined a Generation Like Avatar: The Last Airbender

Everything changed when Avatar: The Last Airbender premiered.

In the 20 years since its release, Avatar: The Last Airbender can be counted among the most successful new fantasy franchises of the modern age. The original series was both popular and critically well-received, spawning not only a sequel cartoon, but multiple live action adaptations, comics, novels, video games, toys, a trading card game and even a concert series of the score. But what it meant to a generation of fans, especially those that consider it a watershed moment in animation, is much bigger than any assembly line of tie-ins or spinoffs. In a way, Avatar has come to represent them.

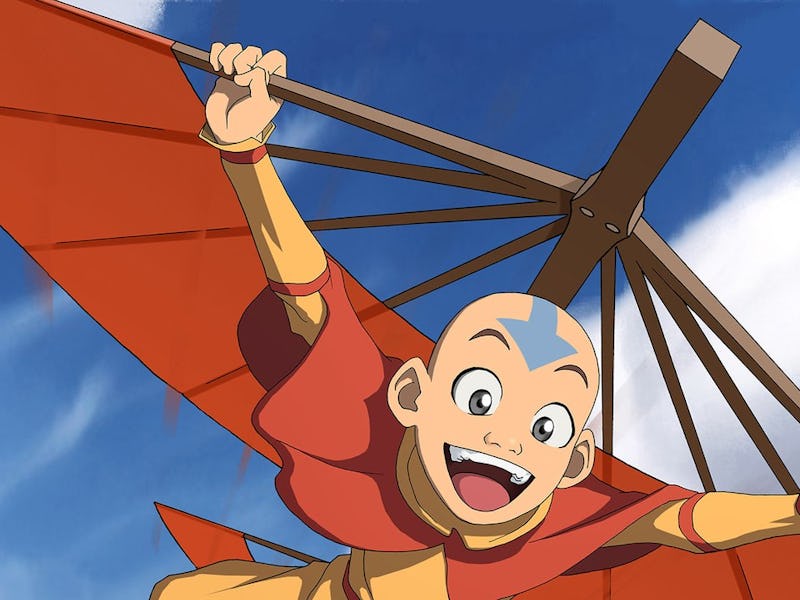

The story of Avatar: The Last Airbender is both constructed out of familiar adventure-story archetypes and its own unique mythology. Aang, awakened from an icy coma by new friends Katara and Sokka, ventures across the land in an effort to learn various elemental “bending” techniques. He also must eventually stop the conquest of the vengeful Fire Nation and live up to his destined spot as an incarnation of the “Avatar,” a spirit that embodies the peaceful balance of not only the elements but the people of the world.

When you begin to watch Avatar, one thing is clear from the onset: It’s a series that wears its anime influence on its sleeve. Creators Michael DiMartino and Bryan Konietzko were not only unabashed devotees of the Japanese medium, they also didn’t view anime as cheap overseas productions but rather a vital method of storytelling. From the character designs to the exaggerated expressions to the intricate action scene choreography, much of Avatar seems concocted to try and speak anime’s visual language.

It didn’t come out of nowhere. The ‘90s had been a burgeoning boom period for anime in the United States, culminating in its final years with a flurry of things like the mega-successful Pokemon, Toonami’s influential offerings, and the rising availability of the medium on home video. Those that watched Avatar were primed for it through this — “anime” had become a household word instead of something that licensors tried to hide from potential customers for fear of alienating them. Joined by series like Teen Titans, The Jackie Chan Adventures, and The Powerpuff Girls, Avatar wasn’t technically anime, but it did attempt to harness and embrace its strengths.

One of those strengths was its serialized narrative, something common to anime, but an aspect that American cartoons had long had a love-hate relationship with (the mindset was that if a kid happened to catch an episode out of order, they’d get confused and lose interest). Avatar could be enjoyed if one caught a random installment — “Zuko Alone,” for example, is considered one of the series’ best episodes because, though it uses flashbacks to illustrate the wider lore of the titular Fire Prince, the present day story has a rich emotional arc that’s great even on its own.

But Avatar was best seen within its wider picture. This, too, was familiar to its audience. Shows like X-Men and Gargoyles and Toonami fare like Dragon Ball Z and Sailor Moon turned the can’t-miss-or-you-might-get-lost attitude to viewership into a feature, not a bug. If anything, it was a sign of trust in its audience that they could keep up, not just with the machinations of the plot but with the shifting emotional story involved. Like many great cartoons, Avatar spoke directly to those watching rather than talk down to them.

The discovery of a boy in an iceberg kicks off the events of Avatar: The Last Airbender.

While Avatar could be very funny and had moments of bouncing levity, gleefully exploring its own fantastical potential with as much curiosity as Aang himself, it was clearly a show aimed at older kids. Its home channel, Nickelodeon, was no stranger to this — shows like Rocko’s Modern Life, Ren & Stimpy, and Invader Zim had leaned a little darker. But Avatar: The Last Airbender added a thematic depth and a willingness to explore traumatic social dynamics that meant that those that came for the escapism also had to grapple with the horrors of its world. It was a series that wasn’t just about becoming a better person, but coming to terms and perhaps even atoning for what you’ve done before.

This, too, was endearing. Adventure cartoons were no stranger to potentially making you feel things — the ‘90s had been marked by three straight Batman cartoons with villains that were just as empathetic as they were terrifying. But it gave animation fans something to chew on that other TV-watching demographics were getting in spades. Television had entered a new golden age of sorts, and boundary-pushing shows like The Sopranos had quickly become blueprints in the onscreen renaissance. Why shouldn’t those hovering in the preteen and teen set get to enjoy a cartoon that asked its own relative questions about morality and tried to dig into the impulses (and eventual healing) of abuse and warfare?

Since its release, Avatar: The Last Airbender has been regularly named one of the greatest animated series of all time (IGN has it at #35 out of 100, TV Guide has it on their list, and Comic Book Resources fits it in at #14 out of 45). Its legacy as an incredible cartoon has certainly been affirmed. But to the generation that watched it in 2005, it was both that and the pinnacle of something that had been building their whole lives. It reflected the way that Western animation had changed in the years prior and as such, the audience that changed with it.