Antlers review: The freakiest folk horror of the year is here

Produced by Guillermo del Toro, this creature feature has teeth.

Scott Cooper tells ghost stories.

Antlers, hitting theaters this Friday, is the director’s first project set explicitly in the horror genre. And yet Cooper’s previous films — grim, rusted-out portraits of life in America’s margins — have been haunted by darkness.

Through menacing atmospheres and meditations on the sins of the father, Cooper’s films suggest that something sinister long ago seeped into the settings and souls of his characters.

And so, it should come as no surprise that Antlers, set in a forgotten pocket of Oregon, exudes a profound sense of despair even before mythological forces enter the equation. Life may have once been manageable in the film’s small-community setting, but that was before this once-prosperous mining town was starved of resources and flooded with opioids.

Boarded-up gas stations and rotting factories stand as silent monuments to industrial decay. The line for a pill mill stretches around the block. For those who live in this dying place, jobs are hard to come by, and hope isn’t falsified to reassure the children. Educators privately share their concerns that students who’ve stopped coming to school were told to do so by their parents, who didn’t want administrators to smell meth on their clothes.

When one such father, Frank (Scott Haze), enters an abandoned mine shaft to cook, he leaves his younger son Aiden (Sawyer Jones) behind in the truck. The flare he ignites to hold the dark at bay illuminates the tunnels with a dull red glow, as though he’s stumbled into the underworld. Perhaps he has, given the terrifying force he encounters deep in the mines.

Director Scott Cooper and Jeremy T. Thomas on the set of Antlers.

In this striking early sequence, Cooper establishes an oppressive atmosphere for Antlers, though the rest of the film can’t match its rich use of light and shadow. Instead, the film becomes more character-focused and settles into a stark, menacing slow-burn as we meet elementary school teacher Julia (Keri Russell, of The Americans fame) and her withdrawn student Lucas (Jeremy T. Thomas, impressive in his first leading role).

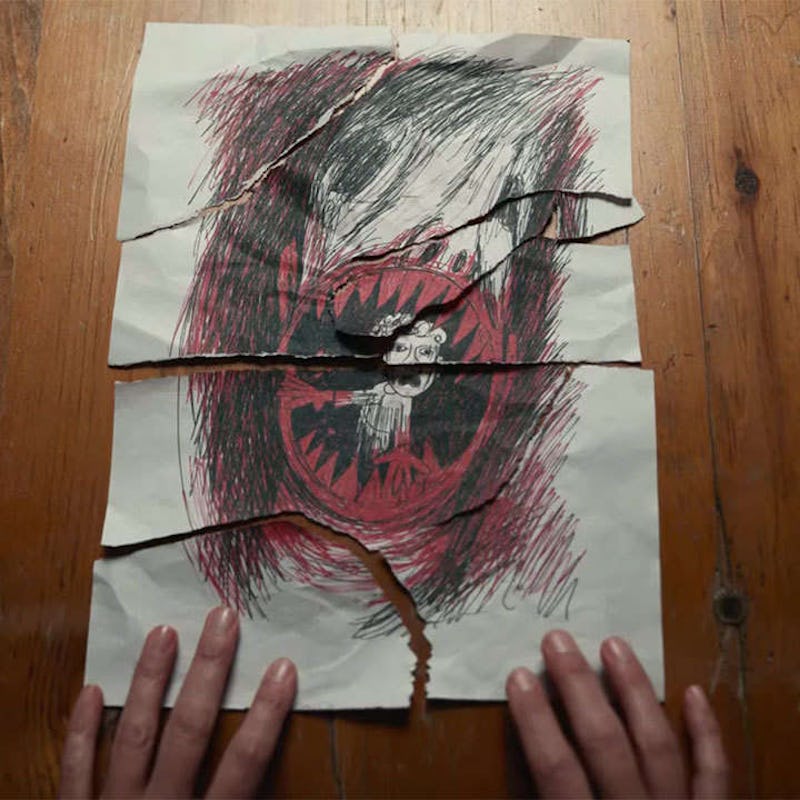

A survivor of childhood abuse and still healing from its horrors, Julia senses real pain and fear in Lucas, who comes into class covered in soot and toting a book of disturbing drawings. What could lead an otherwise sweet-natured young boy to sketch these demonic, sharp-toothed creatures, ripping one another limb from limb? Julia surmises that something’s going on at home, though she doesn’t know half of it. After school, Lucas catches animals in traps then butchers them as food for Frank and Aiden, who are locked up and in the throes of a hideous transformation.

The strain of all this is grinding Lucas down, though it’s suggested his father’s battles with addiction — and, it’s implied, his use of Aiden as a mule — forced Lucas to accept such responsibilities a long time ago. Within the film’s economically ravaged setting, such circumstances are not uncommon, and Julia’s town-sheriff brother Paul (Jesse Plemons) isn’t surprised by her concern for Lucas, though he knows less what to do with it.

Jesse Plemons, Jeremy T. Thomas, and Keri Russell in Antlers.

Paul even seems unsure how to approach his sister, who’s recently returned to town and made it her mission to “save” one young boy. Julia got away from their abusive father. Paul stayed behind, and his affable lawman demeanor cracks in one scene where he reminds Julia she has no idea what was done to him after she left. Plemons and Russell are skilled performers, and they handle these agonized moments with grace. Still, their dynamic is one of many in Antlers that get short shrift as the film leans into its genre elements to become, more or less, a creature feature.

To risk spoilers, Antlers draws its darkness — and its title — from the Algonquin myth of the wendigo, in which a dark spirit possesses a man and turns him into a feral, elk-horned creature with a taste for human flesh. The more it eats, the hungrier it grows — and, intriguingly, the weaker it gets. But the film’s central characters are uniformly white, and their unfamiliarity with Indigenous folklore drives the horror. Eventually, retired sheriff Warren Stokes (First Nations actor Graham Greene, whose role appears strangely diminished) emerges to explain the wendigo’s ancestral roots in the landscape, making it clear that the creature’s emergence is a consequence of natural resource exploitation and extraction.

To trace the wendigo back to its folkloric roots is to find a scathing critique of capitalism and a monster brought about by colonial greed and consumption. Left to starve in the dead of winter after colonists ransacked their lands, Indigenous populations resorted to cannibalism, leading to the creation of the wendigo — or so the legend goes. Allegorically, the creature appears as a corrective force and a vengeful spirit, sent to punish those whose depletion of the land has caused a critical imbalance in nature.

Jeremy T. Thomas and Keri Russell in Antlers.

Within Antlers’ holistically drained setting, the wendigo makes for a rich metaphor. A primordial rejoinder to economic stress and environmental devastation, it can also be used as a vehicle to navigate the mistreatment of Native Americans in the area (though this angle is disappointingly underexplored in the film).

More effective is the way the wendigo reflects the scourges of addiction and familial abuse. Note the way that, after a prolonged period of withdrawal-like symptoms, the wendigo eventually tears out of Frank, antlers sprouting out of his mouth in a grotesque, flesh-rending manner that signals the ultimate annihilation of his humanity.

Guillermo del Toro, one of our foremost masters of the macabre, executive-produced Antlers and is said to have shepherded it to the screen. Glimmers of his emotionally baroque fairy-tale horror shine through in the film’s creature design, which positions it as something closer to a pagan god than a monstrous outcast. (Its Predator-like mandibles also harken back to del Toro’s Reaper design from Blade II, previously recycled into the strigoi of his FX series The Strain.)

That the monster’s appendages are made of bone adds a dark intimacy to its carnage. As the wendigo impales and penetrates its prey, the film frames these attacks as violative and profoundly destructive. One is reminded also of “savaging,” the behavioral anomaly in which wolves fatally maul their young, typically when they sense that something’s wrong with the environment. If these people live on poisoned ground, where nothing good may grow, could the wendigo’s retribution be considered as a show of mercy, even an act of love?

Keri Russell in Antlers.

Julia’s interest in Lucas stems from her need to save someone from the same abuse she endured. She’s unprepared to face a supernatural threat, but we’re made to understand that Lucas experiences his father’s transformation first as a child, psychologically fracturing under the pressure of tending to his unspeakable needs.

“I just have to feed him, and he’ll love me,” whispers Lucas, and Julia shudders in recognition. Their abusers may wear different faces — and the wendigo, in one rattling sequence, is revealed to be wearing Frank’s — but Julia and Lucas are connected as survivors, struggling to break cycles of abuse they were forced into.

Under all this narrative weight, Antlers’ scant 99-minute runtime makes it feel more truncated than trim. One hopes against hope that a director’s cut will eventually see the light of day. The trailers include plenty of footage excised from this theatrical version, and Cooper’s work is undercut by a rushed third act that doesn’t marinate in all the mood he so carefully establishes. One wonders whether Disney-owned Searchlight Pictures (which inherited Antlers after the Fox merger) balked at a longer, more gothic meditative vision from Cooper and del Toro, insisting on cuts that would allow it to be marketed as a straightforward Halloween spooker.

And so Antlers ends on an abrupt — yet fittingly bleak — note, offering grim answers to its questions of psychological trauma, cyclical harm, and communal devastation. Unsatisfying in the moment, the film’s denouement is more chilling in hindsight, as the significance of its final shot sinks in. For all Julia endures in her efforts to relieve Lucas of his terrible burden, she succeeds only in transferring that responsibility to herself — and ensuring the horrors ahead will hit even closer to home.

Antlers opens in theaters this Friday.