“The wendigo takes many different forms.”

'Antlers' director explains the movie's monster and that twist ending

by Isaac FeldbergAmerica is a horror story.

That’s the conclusion that filmmaker Scott Cooper has reached across all his darkened portraits of our decaying heartland, from spiritually stained crime saga Out of the Furnace to morosely existential Western Hostiles. So perhaps it shouldn’t surprise that Antlers, Cooper’s first out-and-out horror film, ends on such a brutally unsettling note.

“I tend to never make the same film in the same genre,” Cooper tells Inverse. “The great danger as a filmmaker is in doing safe work. I always like to be in an uncomfortable space.”

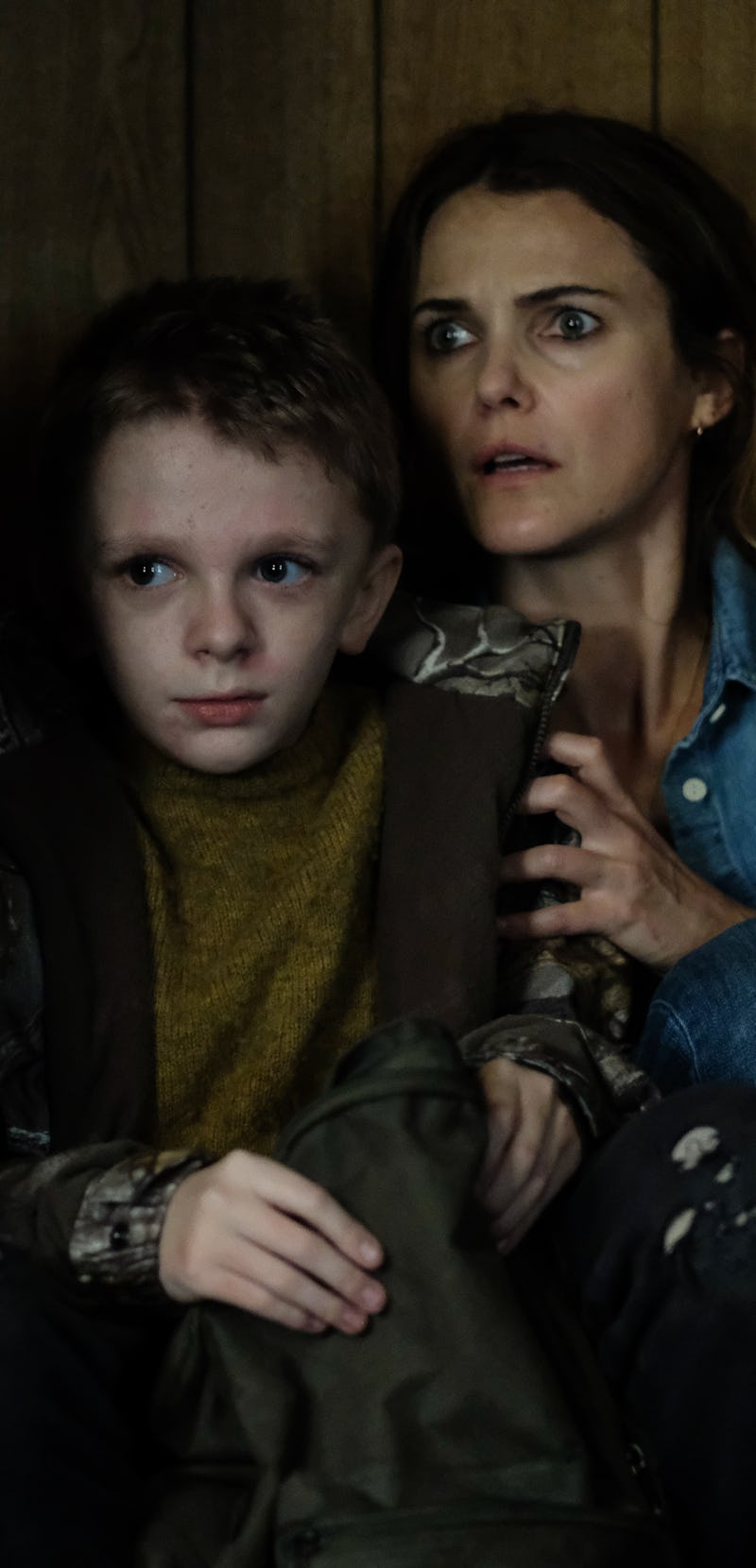

Now in theaters, Cooper’s supernaturally charged thriller is set in a small outpost in rural Oregon, a ghost town in the making where industrial collapse and a deeper spiritual stagnation hang over the residents like a fog. In this despairing place, middle-school teacher Julia Meadows (Keri Russell) must battle a mythological entity in order to save her student, Lucas (Jeremy T. Thomas), from a ghastly fate. Spoilers ahead for Antlers.

Gradually, it’s revealed that Lucas is struggling to help his younger brother Aiden (Sawyer Jones) and meth-cook father Frank (Scott Haze), both of whom have been transforming in hideous ways since encountering a horrifying supernatural presence deep in an abandoned mine shaft on the edge of town. After Frank goes through withdrawal-like symptoms while locked in the family’s attic, he’s overtaken by the emergence of a monster that sprouts antlers from his mouth and eventually cracks his body open, like an insect emerging from a carapace.

That monster is revealed to be the wendigo, which has deep roots in Native American folklore, though Julia and her sheriff brother Paul (Jesse Plemons) are unaware of this. For Cooper, it was paramount that the creature at the heart of Antlers fit tonally within the dark world he set out to create.

“The wendigo takes many different forms,” Cooper says. “First and foremost, it's a spirit, but it can also serve as an addiction. It can serve as a metaphor for the environment. It can serve as a metaphor for people who are struggling with grief and trauma.”

The wendigo, explained

3D illustration of a Wendigo.

The Algonquin myth of the wendigo involves a dark spirit that possesses a man and turns him into a feral, elk-horned creature that craves human flesh. The more it eats, the hungrier it grows — and the weaker it gets. One of the physical attributes this creature’s known for is its fearsome rack of antlers, which allow it to maim, gore, and fatally penetrate prey.

A sense of communal grief and familial trauma pervades Antlers, though the mythology of the wendigo is scarcely explored outside of one expository scene with First Nations actor Graham Greene (Dances with Wolves, Wind River), who plays a retired lawman familiar with the wendigo.

Keri Russell stars in Antlers.

“Here you have a white Anglo-Saxon Protestant telling a Native American folkloric mythology story,” says Cooper of his approach, adding that the cultural ignorance of his main characters, all of whom are white, was crucial to the story.

“For the audience to understand what the wendigo is, and what it means, you can't have Jesse Plemons discuss it,” he continues. “You can't have Keri Russell discuss it, because they don't own it. They don't understand that. So Graham Greene, of course, in an earlier iteration, had a larger part in the narrative.”

But in the current theatrical cut of Antlers, Greene’s role has been whittled down to just a few scenes, one in which he explains the mythology of the wendigo to Russell’s disbelieving Julia.

“In the end, it's upon his shoulders to help inform us as to what this really means, what it means to his culture, and what it means to Indigenous peoples, and there’s really no way around that,” says Cooper, expressing regret that the actor’s role wasn’t more sizable.

“It’s a miracle that any of it works.”

“What's important to me is that I was given permission by people who most know about the wendigo — and who covet it, and who understand it far better than I do — to tell this story,” he adds.

The production employed Grace L. Dillon, a professor in the Indigenous Nations Studies Program at Portland State University, as its Native American advisor, and the film’s vision of the creature largely stemmed from Dillon’s expertise. “That was important to me because it means so much to their culture,” says Cooper.

Antlers was executive-produced by Guillermo del Toro, and the 99-minute cut of the film now hitting theaters constitutes an unholy marriage between the filmmakers’ sensibilities: Cooper’s uncompromisingly grim and grounded, del Toro’s more fantastically grotesque. “It’s a tough one; it falls between a few different genres,” says the filmmaker. “It’s a drama that deals with holding up a dark mirror to the fears and anxieties of Americans, but it’s also a creature feature.”

Scott Cooper and Guillermo del Toro on the set of Antlers.

Early reviews of the film, including mine for Inverse, have critiqued Antlers for not nailing that balance, with an abrupt shift around the film’s hour mark from dread-steeped drama to more straightforward (though visually striking) horror. “Trying to weave all that into a story is ambitious,” Cooper acknowledges. “It works on certain levels.”

Speaking about Antlers, Cooper is candid about the challenges posed by the project — some of which mandated that he suppress his own creative instincts. Asked whether Antlers was trimmed down in post-production, Cooper acknowledges that, yes, “there was a much longer version,” glimpses of which are still visible in earlier trailers.

“They want more Guillermo del Toro and less Scott Cooper.”

“You take my sensibilities and Guillermo del Toro's, and they're incredibly different,” says Cooper. “And it's a miracle that any of it works, quite frankly.”

The filmmaker speaks highly of del Toro, calling him “the foremost monster and creature creator that we have,” and it’s clear that the Oscar winner’s involvement is in large part what convinced Cooper to tackle Antlers. But, occasionally, a certain air of resignation creeps in as Cooper discusses the project. “When you're making a film, and you're selling it as a horror film to people, I think they probably want more horror,” says the filmmaker. “They want more Guillermo del Toro and less Scott Cooper.”

Antlers’ setting explained

Scott Cooper and Jeremy T. Thomas on the set of Antlers.

Cooper’s most successful work on Antlers comes early, as he establishes a strong, ominous sense of place.

Lucas trudges home from school through rusted-over train tracks and the wreckage of industrial buildings that went dark long ago. “I'm really most interested in towns and people that are left behind, people who live on the margins and whom you don't often find in cinema, certainly in larger-budgeted cinema,” says the director, who’s set previous films in a Pennsylvania steel-mill town (Out of the Furnace) and crime-ridden South Boston (Black Mass).

Though it’s set in coastal Oregon, Cooper shot Antlers just north of Vancouver. “There's a certain gloomy mystery to it,” he says, with “all these folds and crevices where both monsters and humans alike can hide from their anxieties and fears.”

That atmosphere was important in terms of heightening the emotional desolation felt by the film’s characters.

“When a small town closes, when a factory closes, what does that [do] to that life?” says Cooper. “People [in my movies] deal with the types of fears and anxieties that all Americans are dealing with, but they're dealing with them on a much deeper level. That interested me in terms of the real horror of the film, as opposed to the wendigo.”

Antlers’ twist ending explained

Keri Russell in Antlers.

Never is Antlers more torn between Cooper’s trademark despair and del Toro’s more giddily macabre touch than in its final third. After bringing young Lucas home with her, Julia learns that the wendigo is more than capable of tracking its quarry. An attack ensues by the shed behind the Meadows’ house, with her brother Paul badly injured and his colleague Dan Lecroy (Rory Cochrane) fatally mauled by the wendigo.

After a frantic skirmish that nearly takes out Julia, Lucas and the wendigo abscond to the same abandoned mine where Frank originally encountered the creature. Following them there, Julia barely survives her climactic confrontation with the wendigo, but she does so at a terrible cost. In order to rescue Lucas — who comes to her aid at the last moment — Julia kills the adult wendigo that has emerged from Frank (and, in a ghastly reveal, is still wearing what remains of his face as a tattered mask). She also sees that young Aiden is in the midst of his own horrific transformation and ends his suffering, ensuring that Lucas doesn’t witness his brother’s death.

On that grim note, the violence is over — until an epilogue, set sometime later, picks up with Julia still watching over Lucas. She walks with Paul, who’s recovering from being mauled by the wendigo, along an embankment by a lake. She doesn’t notice that Paul’s eyes are leaking black liquid, as Frank’s had previously; it appears the creature has survived its encounter with Julia by jumping to another host.

Cooper knows that audiences will be shocked by this conclusion, but it’s not merely meant to provoke. “We see early on in the film that Jesse Plemons’ character, Paul, is struggling, certainly — maybe not addicted, but is involved in some way — with some type of opioid or some type of drug,” explains the director.

Jesse Plemons, Jeremy T. Thomas, and Keri Russell in Antlers.

“America has an addiction crisis, whether it be opioids, methamphetamines, or alcoholism,” he adds. “And we see that, midway through the film, when Paul’s well in over his head, that he turns to that as some sort of medication or an elixir that will help him through these moments.”

Paul’s drug use doesn’t get in the way of his day job as sheriff, exactly, and he’s far from the only character involved with substances. But this nasty habit leaves him vulnerable to the wendigo, which feeds off addiction and pain. “We understand that Paul is struggling with these types of issues: personally, professionally, and also in terms of his relationship to his sister,” says Cooper. “He, unfortunately, is the perfect surrogate for this particular affliction. And at the end of the film, we see that it's his turn in the barrel next.”

That’s also bad news for Julia, who thinks she’s finally free of the wendigo. “Unfortunately, we've seen just what Julia has had to face with Lucas's young brother, what she's had to do to him,” says Cooper. “And then, Jesse's character says to her — in thinking about Lucas and looking at him — “Could you kill something you love?” Well, a minute later, we realize that she may have to. It may have to be her brother.”

It’s a brutal ending — but one that underlines the thematic depth Cooper wanted for the wendigo, which represents more than just the Indigenous folklore from whence it emerged. “It means so much throughout the fabric of the story: generational trauma, familial abuse, addiction, desecration of the earth, all these things that sound almost high-minded,” he says. “But when you're telling the horrors of what it means to be an American today and not just straight horror with the wendigo, it's a tall task.”

Looking back on the project, does Cooper think Antlers was up to the challenge? “I think it certainly works in some aspects of the film,” he says, cautiously. Does that mean he’s finished with horror? Don’t count on it. Cooper grew up watching horror films, and Antlers “certainly won’t be my last,” he says. “The next one might not be a creature [feature,] but I'm not done with the genre yet.”

Antlers is now in theaters.