The Savage 2000s Satirical Thriller That Became Terrifyingly Relevant

25 years later, American Psycho is a misunderstood classic.

American Psycho is a comedy. A dark streak of humor runs through Mary Harron’s adaptation of Bret Easton Ellis’ 1991 novel — a pointed satire of corporate greed, yuppie culture, and rampant consumerism — in which a wealthy investment banker eventually spirals into madness and murder. Not so for certain sections of the manosphere, in which Patrick Bateman is revered, unironically, as a “sigma male” (the mysterious, lone wolf version of the “alpha male”) for his bank balance, hustle culture-oriented mindset, and his irresistible appeal to women.

His sharp jawline and sculpted physique are held up as an ideal by the “looksmaxxing” community, young men fixated on maximizing their appearance to become the most attractive version of themselves. Bateman’s punishing, ridiculously elaborate morning routine, which involves two cleansers, two scrubs, an anti-aging eye balm and a thousand crunches, is now the standard of self-care. “Patrick Bateman is (almost) the ideal male,” reads one post on a looksmaxxing forum. “Great fashion sense, harems of women, soothing, masculine voice and accent…the only thing he lacks is height (he is 5’10).” American Psycho is a comedy, but somewhere along the way, some of its audience stopped being in on the joke.

If online, the “sigma” is defined by a non-conformist, highly individualistic attitude, then Bateman (Christian Bale) is a laughably poor candidate for the role. Take an early scene of his fiancée Evelyn Williams (Reese Witherspoon) asking him why he doesn’t quit a job he claims to hate. “Because. I. Want. To. Fit. In,” he replies, enunciating each word emphatically. So much for being a lone wolf.

Far from shunning the hierarchy, he’s obsessed with it. In one of the film’s funniest scenes, an evisceration of petty corporate one-upmanship, Bateman and his colleagues earnestly compare the font and coloring of their business cards. Each newly presented card is punctuated by the sound of a sword being unsheathed — a nod to how these men elevate insignificant minutiae to a cutthroat competition. Bateman’s inner monologue betrays his masked expressions; he works himself into an anxious frenzy, and then a trembling rage, over his card falling short.

And he’s as conformist as they come. Just before he slaughters a colleague (Jared Leto) he’s deeply jealous of, he launches into a lengthy praise of the Huey Lewis song “Hip To Be Square,” rattling off what he perceives to be its themes — “the pleasures of conformity and the importance of trends” — in a complete, comic misinterpretation of the band’s intent. His gnawing need to blend in conversely means he doesn’t stand out: a recurring joke in the film involves him being mistaken for another colleague, who not only resembles him, but also prefers the same brands. While he does engage in a threesome — no doubt going up in sigma estimation — he spends most of it gazing at himself flexing in the mirror.

Bateman’s vanity is only rivaled by his insecurities, which become the frequent butt of the joke in Harron and co-writer Guinevere Turner’s script. He’s gripped by panic after breaking into his victim’s apartment, but only because it’s more expensive than his. His incessant need for validation emerges even during an interrogation, when his stony composure breaks into a grin at the detective’s (Willem Dafoe) admiration of his posh address. When he is driven to near tears, it’s at the grim, tragic prospect of not securing a “decent” enough table at a restaurant; the instant relief he experiences when he does is overwhelming. A recurring source of aggravation for him, and amusing gag for the audience, is him being unable to secure a reservation at the city’s most exclusive hotspot.

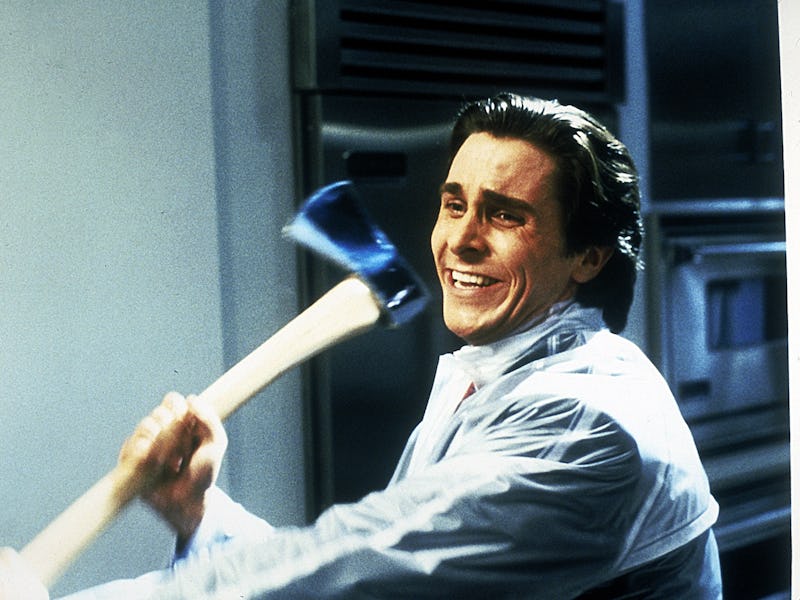

Bale’s unhinged performance understands how ridiculous Patrick Bateman is.

Constantly envying his fellow men, Bateman comes across as not quite human himself. To focus on his well-moisturized exterior is to fail to see how he’s been corroded internally, consumed by thoughts of desperation-driven bloodlust, characterized by a disturbing lack of emotional depth. He’s the ideal consumer, but a hollow shell of a man. He cares, so much, about utterly meaningless pursuits that he fixates on them to the point of torment. His insatiable desire for more can only be temporarily quelled by his homicidal excursions.

And yet, in a conformity-rewarding capitalist hellscape primed to churn out either Bateman clones or charmed admirers, no one seems to notice. One colleague (Matt Ross) mistakes his strangulation attempt for a seduction technique. Women call him “sweet” and “the boy next door,” oblivious to his vacant stare and the elaborate opinions he delivers as though reciting someone else’s words. His repeated references to serial murderers, couched as jokes and “fun facts,” raise no alarms. He wants so badly to belong, even to groups he clearly considers inferior, that the pressure to fit in is crushing and even long-sought social acceptance provides no catharsis. His misery goes unnoticed, by the characters that surround him, and now by the internet forums that put him on a pedestal.

Is Bateman to be idolized? Twenty-five years on, the film’s answer is as loud and unsubtle as the revving chainsaw he brandishes. The clue’s right there, in the title. The ultimate joke is on the people who still miss it.