'Toy Story 3' and 'WALL-E' Animator Carlos Baena on Going Independent

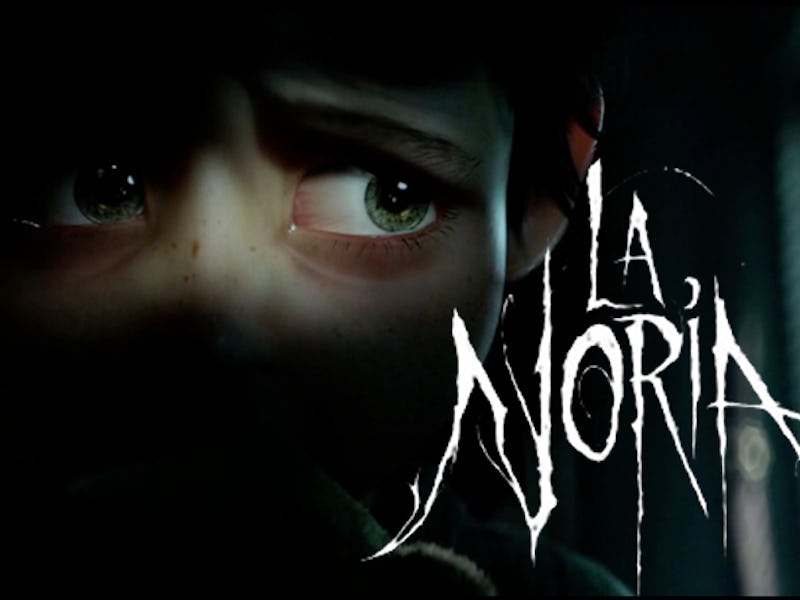

The veteran's next project is a short horror film carefully designed to haunt your dreams.

This article by Victor Fuste originally appeared on Zerply.

Carlos Baena, director of the animated short film La Noria., is breaking new ground in the field of animation with his newest project. The independently produced animated film blends a strong personal story with a heavy dose of horror. Find out more about this team and their beautiful, unique film by visiting the project’s Indiegogo campaign page.

La Noria Teaser

Tell us a little about where the idea of “La Noria” came from and what inspired you to take on the challenge of doing an independent short film.

La Noria takes different personal feelings, emotions and people in my life as inspiration. For example, there was a year in my life where a lot of things in my life collided. Physically, emotionally, professionally, it was just a lot of things that hit me all at once over a short period of time and it was all very rough on me. That was one of the inspirations – some of those emotions that also helped shape me and grow. It isn’t biographical. We adapted those elements into a much simpler narrative to fit within a dark horror short film. Darker films are something I’ve been wanting to do since my days in college when I used to do dark creature work. In late 2010, I started talking to artists to see if they wanted to help me in making this project.

Around that time, great live-action movies that came out such as Pan’s Labyrinth, The Orphanage and Let the Right One In. I remember thinking, “Gosh, why aren’t we seeing stuff like that in animation?” I even starting using Let the Right One In‘s soundtrack in the [story] reels, as it had the right dark yet beautiful sensibility we were after. Eventually it got to the point where we decided to even reach out to the film’s composer, Johan Söderqvist. After reaching out more than a few times to his manager, he ultimately ended up joining us. It’s been a wonderful collaboration/friendship since. You can get so much tension and so much creepiness with the music.

La Noria Screenshot

Another influence was Alejandro Amenbar’s The Others and Victor Erice’s Spirit of the Beehive. I personally love vintage photography as well – things that are old and have character within themselves. I grew up going to the Madrid flea market with my father and brother since I was really little. There’s something about the history of objects and the history of places that always been very inspiring. Ultimately with this film, it’s been a combination of a many things that I wanted to see in animation.

What is it about those directors’ filmmaking style and their particular brand of horror that you wanted to bring to La Noria?

From my end, there is something about the themes of innocence and darkness in those films and how what we go through in our youth can haunt us for the rest of our lives. When I went through that difficult time in my own life, I started reaching into not just the adult version of me, but also the little kid version of me just to connect some pieces. I looked for the tools that helped me get through that. Art was a big one for me. There’s some universal things that we can all connect to.

With this film, I was trying to pay the respect to what those filmmakers had been doing in live-action. I also wanted to find a way to combine a dark and sad theme with something beautiful. The more I listened to Johan’s music in our reels, there was something about it that didn’t feel like just horror. I didn’t want to do horror for the sake of horror. Instead I wanted to tap into other things that aren’t just external horror, but also the complexities of the internal.

La Noria

Animation often gets pigeonholed as a “genre” when in reality it’s just a medium, a different form of filmmaking. Why is it do you think that larger studios have been more hesitant to make animated films in genres such as horror?

I feel that it’s always a financial decision. It costs so much money to make animated films. The budget for a feature length animated movie is so much bigger than for a live-action movie. These days, you can get a smaller camera (Alexa, black magic, dslrs) and do a low budget feature film at an affordable price. You just can’t do that in animation. If you want people to be paid what they should be getting paid, you can’t just say, “I’m going to make this film for $10,000” – it just doesn’t work like that.

Part of the motivation in making this film was that we wanted to push for that change – not having animation that is only for kids. These movies don’t have to be just horror. There are a million other styles of movies I would love to see in animation. I would love to see a movie like Alien or Seven done in animation – I would pay triple to see something like that!

I would love to see a proper film noir – black and white all the way.

Absolutely. Who’s to say we couldn’t make a film noir? Or something like The Godfather or American Beauty? There are movies that have so many distinct personalities and sensibilities, but they’re nowhere to be found in animation. I feel like it is slowly changing though. You have films like The Illustionist, The Triplets of Belleville and Song of the Sea for instance – those films are amazing! You want to see more films like that. Don’t get me wrong, it’s fine to have comedy and playful moments that kids can enjoy. But I don’t think the overall tone of a film should be compromised by how many jokes you can put in it.

I think it’s a matter of proving to the general audience that we can do a lot more with animation. I remain hopeful that things will change. Right now, I see the gap narrowing in places like video game cinematics which are becoming more adult. You cut together six cinematics and that’s a feature film. Who’s to say that all the teenagers that are playing video games wouldn’t want to go see a movie that’s more like the cinematics. It’s great to fantasize about animated films made for younger audiences coexisting with animated movies made for teenagers to adult audiences – and they both make money. That’s my hope at least. Truth is, these more adult movies just aren’t being made because there hasn’t been that one movie that has made a studio loads of money yet. When that’s the case, they’ll start seeing animation differently.

That’s the thing – it just takes one movie.

Just one! Just one movie. Take Anomalisa. Those filmmakers clearly know their audience, regardless of the medium. You do that more and more with other animated films and things may start to change.

La Noria Closeup

Since you directed this film, what have been some of the biggest lessons you’ve been able to carry over from your time as an animator? How are the experiences different?

As an animator, you have your shots, your sequences that you’re assigned to. Then you can easily just go to your office, shut your door and start working on them. The difference with the director role is that you need other people to help you do those things you envision in your head. In a way, it’s more extroverted. You have to talk a lot more whereas as an animator, you can just do it. Sometimes it’s a lot easier to just do it.

A big part of my learning was figuring out how to have other people see what I’m seeing in my head. How can I get my crew to help me visualize it? Because we’re doing this independently, it’s not like we have a big budget to pay people to do this. They’re doing this with their free time because hopefully they believe in the project. So you have to walk a fine line in terms of how picky you can be. There have been a lot of battles where you have to compromise and move onto the next thing in order to finish the film – even though in my head, I’m nitpicking it to death.

What sorts of challenges did you have overcome in trying to communicate to another artist how to visualize what was in your head?

The more that I worked, I found tools that allowed me to quickly demonstrate what I was after. Whether it was things like finding references or doing drawovers in Photoshop, that stuff was really helpful. Also, putting together sizzle reels to show the tone and the feeling we were going after. That would help the crew immensely and then we would start working. More so than overcoming, it was more of a process of figuring out how best to clearly explain my thinking.

In the case of animation, if it’s something that animator is still not getting, I would get the help of another animator or just jump in Maya and then quickly show them what I had in mind. I wouldn’t animate it per se, but I would show what I was thinking and let them take it from there.

La Noria Poster

One of the more intriguing parts of the campaign page was the part about the collaborative technology like Artella that were used in the production process. What can you tell us about that and can people sign up to use it?

We started Artella at the same time as we were starting La Noria. We knew we didn’t have a physical place to work on the film and there were many artists that I wanted to work with on this project, but they were all over the world. Basically we had a distance problem. As we were working on the story for La Noria, we also started building this tool called Artella from scratch with help from a lot of people who have had experience at different studios and their pipelines. The tool would allow us to work with assets and scenes all in the cloud. You have all the check in/check out processes and all the versioning, permissions, etc.

We wanted to make Artella accessible to independent artists or whoever wants a pipeline. We always had this idea of something that you can change to suit your needs from a pipeline standpoint. You can create your own folder structure, reference naming, etc. Our whole goal was to make everything a lot more flexible. It’s very easy for a pipeline to become this massive machine and to change anything is like taking the wrong piece out of a Jenga game. We’re still working on finishing the details to get it just right, but our goal was to make a pipeline that was more like a Rubix cube in that you can change things around and it won’t collapse.

Artella had a fantastic group of programmers from Animation Mentor while we working out the story La Noria. At one point, we merged the tool with the short film to use it as a beta. From there we discovered a lot of things that worked and some that didn’t and then continued refining.

You also had the support of companies like Autodesk, Shotgun and rendering from Arnold Renderer. For those interested in pursuing their own independent projects, how did you go about putting together those partnerships?

One of the things that became very clear to me early on is that I don’t think I would have enough money saved up just to cover the licensing costs. Plain and simple. Much less, being able to pay for the artists. Here and there we would have a little bit of budget allocated to help us on areas that we really needed a part time or a full time over a period of say 2-3 weeks. That’s where I used my own savings. Then my producer started to put her own money as my savings started going down the toilet.

Our thinking with the licenses was that, at the very least, I could talk to these companies and show them what it was we were trying to do and why. The one situation I didn’t want to find myself in was the “I just didn’t try.” So whether it was the composer, whether it was Autodesk, whether it was Solid Angle, we basically just approached them, presented the film and showed them what we were hoping to accomplish. And they believed in it.

Bobby Beck (Artella), Chris Vienneau (Autodesk), Marcos Fajardo (Solid Angle), Fernando Viñuales (Summus) – these were people who supported and believed in us. To this day, we couldn’t do the film without their support. We’re talking hundreds of thousands of dollars in just licenses and that’s just money I don’t have. (Believe me, I wish I did.) We didn’t have a studio or the licenses, so this really was the only way we could make a film like this. Trust me, there hasn’t been anything that has been easy about this process.

So if you could start over, what are the things you wish you had known from the outset?

The thing we never properly calculated was how long this process was going to take. I took about a year and half off from Pixar and even with that time, we weren’t totally done with the pre-production. Maybe we were moving a lot slower than other productions, but the part that’s maybe not as simple is that you’re working with people who are helping you on their free time. These artists were helping us maybe 2 hours in the evening, maybe a couple hours on the weekend. So when you’re thinking something is going to take a week or two, it will almost end up taking a month or two if not more.

That was a difficult part of the process to accept at first but as time went by, it worked to our advantage. For example, the composer. He would come to me and the producer and say, “I have three movies that I need to compose in what’s left of this year. I want to do the film, but I just don’t know where I can fit in.” What we realized is that money we might not have to actually properly hire somebody, but time we did have. So we said, “How about in between projects, even if it takes an extra year or two?” Having that extra time turned out to be a blessing in disguise.*To follow the film, visit www.lanoriafilm.com

For more information about artists, industry news and projects, visit Zerply.