Stanley Kubrick’s final movie was also his most beguiling

Have a sexy, existentially troubling Christmas.

Stanley Kubrick’s name is synonymous with some of cinema’s most impenetrable and alluring mysteries. Between 2001: A Space Odyssey and The Shining, the famous auteur was noteworthy for refusing easy answers, creating lasting works of art that are still heavily interrogated. So when the filmmaker passed away on March 7th, 1999, a mere six days after screening a cut of his final film for his inner circle, it was guaranteed that Eyes Wide Shut would become a crucial fixation for pop culture’s unyielding obsession with conspiracy.

After reading the Austrian novella Dream Story shortly after the release of 2001, Kubrick spent the next three decades entertaining the thought of adapting it. Arthur Schnitzler’s original story was a quintessential piece of the decadent movement, which championed hedonistic maximalism over logic and realism, and Kubrick initially considered making it an audacious sex comedy.

The final product is anything but; despite its playfulness, the film is uncanny and haunting, and the decision to update the setting from early-1900s Vienna to 1990s New York City throws it into the midst of America’s fixation on the secret lives of the rich and powerful. Exploding outwards from the consequences of Watergate, Americans are obsessed with the idea of a sinister and politically influential cabal of wealthy elites. Eyes Wide Shut takes the paranoia of ’70s conspiracy thrillers and grafts it onto a Christmastime relationship drama, asking us to peel back the curtain and interrogate our own notions of sex, love, and nuclear domesticity.

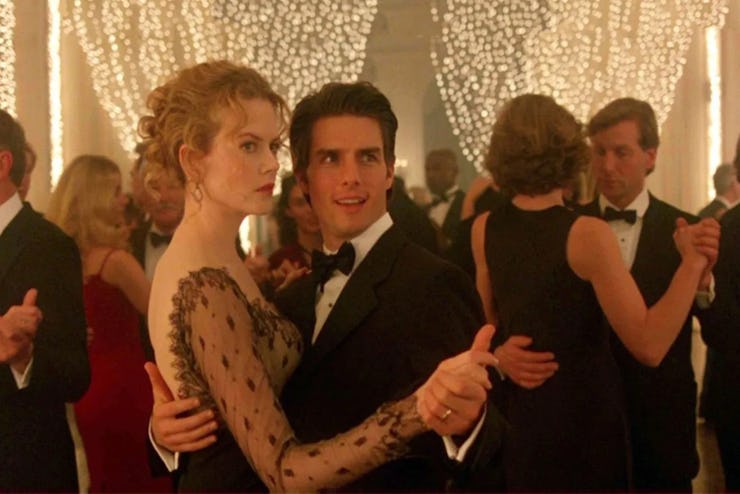

In the ’70s, when Kubrick initially considered adapting Dream Story, he wanted to cast someone who would have “a comedian’s resilience,” such as Steve Martin or Woody Allen. But Warner Bros. wanted a movie star in the role, eventually leading to the casting of Tom Cruise and Nicole Kidman as Dr. Bill Harford and his wife, Alice. Eyes Wide Shut follows Bill’s dreamlike odyssey into an underground world of sexual debauchery and danger after Alice reveals to him that she nearly had an affair the year prior, and there’s a bit of delicious irony in the fact that Cruise and Kidman were married at the time. The film brilliantly shreds Cruise’s rugged ’90s charisma, exposing a rawness and embarrassing vulnerability in the face of Kidman’s coy, multifaceted sensuality.

As a director, Kubrick always maintained intense, complex, and sometimes abusive relationships with his actors. He was exacting upon his two leads, often demanding dozens of takes (including one infamous example of Tom Cruise walking through a door 95 times), but he also intentionally blurred the line between character and performer. He encouraged Kidman and Cruise to share intimate anxieties about marriage with him, and in one stinging example, he asked Kidman to shoot six days of sex scenes with another actor for a short dream sequence that tortures Bill throughout the movie.

Perfect plot points for a classic Christmas movie.

Kubrick’s direction nourishes a distance in Bill and Alice, one born of two conflicting interpretations of marriage. Bill thinks the security his wealth provides is enough to keep Alice content with the domestic expectations placed upon her as a wife and mother, but he’s shocked to discover that she has sexual desires and the agency to act on them. For the first time, he sees her without the curtain of marriage, and it shakes him to the core.

So begins a man’s odyssey to reclaim his masculinity, and Cruise’s journey into the heart of New York City comes alive with Christmas lights and neon-bathed temptation. Larry Smith, who had served as a gaffer on Barry Lyndon and The Shining, was chosen by Kubrick to be the cinematographer, and his mesmerizing camerawork feels as dark and encroaching as something out of Taxi Driver. Much of Eyes Wide Shut’s runtime is dedicated to Bill’s journey through the streets of NYC, as he observes several awkward, illicit, and potentially dangerous sexual encounters. The potentiality of Alice’s affair and Bill’s resulting emasculation seems to open a portal to a dreamscape, one in which Bill discovers just how much of the world around him is governed by humanity’s baser natures.

And cool outfits.

Look no further than the most iconic scene in the movie. After encountering an old friend, a piano player named Nick Nightingale (played by current awards season frontrunner Todd Field), Bill sneaks into an intensely private upper-class party that turns out to be an elaborate masked orgy. Accompanied by Jocelyn Pook’s foreboding and ominous score (responsible for what might as well be the de-facto soundtrack for cults everywhere), both the audience and Bill are thrust into a world where the rich and powerful have bought the ability to release their deepest inhibitions. For most of society, sex is shameful, a temptation to be suppressed and hidden until domesticized, but the open secret of power and status is that it’s nothing more than an excuse to indulge the most instinctual desires of the flesh. It’s a desire that’s so simple it’s almost novel, but as Bill discovers, it’s one that they might be willing to kill for to keep secret.

Like Kubrick’s other works, Eyes Wide Shut has become a passionate source of discussion and analysis, with its real-world implications arguably more popular than the film itself. Conspiracists believe the movie is Kubrick’s bombshell exposé on the real Illuminati, and some go so far as to suggest they had him killed over it. In his typical, ghastly sense of humor, Kubrick does offer to reveal a sort of diabolical conspiracy, even if it’s not the one you might think. Eyes Wide Shut quietly invites you to consider what lies beneath the mask you’ve constructed for your significant other. What secrets do they keep, and what desires do they hunger for? And, perhaps most urgently, how badly do you want to know?

Eyes Wide Shut is streaming on Netflix until December 31.