The 5 most haunting Sir John Tenniel illustrations beyond Alice in Wonderland

The cartoonist is celebrated as today's Google Doodle. Here's a look at some of his most grotesque and powerful work.

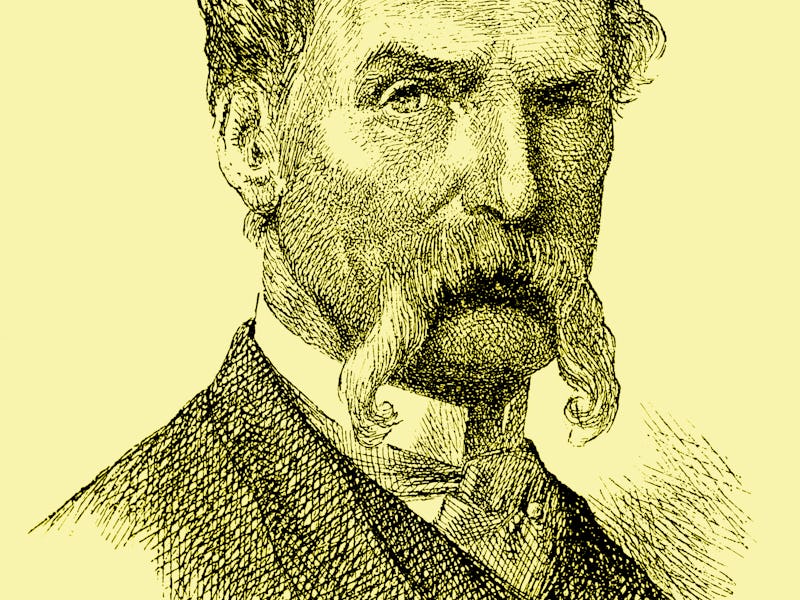

There's never been an artist quite like Sir John Tenniel.

For more than 50 years, the English illustrator and political cartoonist drew the British conscience in his many illustrations for Punch magazine. That's on top of defining a whole generation of fantasy art through his work in Lewis Carroll's novels Alice's Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass, and What Alice Found There.

But it was in his thousands of Punch cartoons where Sir John Tenniel cemented his place in the visual arts, giving contemporary British politics the vocabulary it needed, even if Tenniel was not the most empathetic or sensitive artist. From the struggles of the working class to ghostly apparitions representing sweeping changes and ominous events, Tenniel's Punch cartoons always came with a scathing critique on the failures of bureaucracy.

Today, February 28, 2020, Google commemorates the artist's 200th birthday with its own Tenniel-style illustration (drawn by Matthew Cruickshank) of Alice and the Cheshire Cat.

Google Doodle paying tribute to Sir John Tenniel's 200th birthday.

In his art, Tenniel rode the Nazarene movement of the 19th century, which characterized subjects with shaded outlines and dignified compositions. Tenniel's own innovations included filling in his work with detail, putting his subjects in an extremely specific time and place (which does wonders for political cartoons that comment on issues of the day). Lewis Carroll also cited Tenniel's "grotesque" style to be the main reason Carroll wanted Tenniel to illustrate his novels.

In our own commemoration of Sir John Tenniel, here are five of the artist's most haunting Punch cartoons that define some of the artist's strongest sensibilities and signature motifs.

5. "The 'Silent Highway'-Man" (1858)

Between July and August 1858, central London underwent such hot weather that made the stench of untreated human and industrial waste intolerable. The River Thames, full of toxic materials, becomes the River Styx in Sir Tenniel's piece as Death rows looking for those responsible for not paying to clean up the river.

4. "Britannia Sympathises with Columbia" (1865)

In "Britannia Sympathises with Columbia," Sir Tenniel expresses British sympathy for the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln at the gun of John Wilkes Booth. Tenniel depicts a sorrowful Britannia laying wreaths at Lincoln's body. Columbia weeps clutching the American flag, while an unshackled slave sits mournfully on the floor.

3. "The Haunted Lady, or 'The Ghost' in the Looking-Glass" (1863)

In the 19th century, the seamstress became a ubiquitous occupation for many working-class women in Victorian society. While many were self-employed business owners, just as many worked starvation wages in poor, inhumane conditions. The 1843 poem "The Song of the Shirt" by Thomas Hood, written in the memory of a Mrs. Biddell, described the plight of these women. In Sir Tenniel's 1863 Punch piece, a wealthy young woman sees the true cost of her beautiful dress in the reflection of her needlewoman.

2. "Germany's Ally" (1870)

A recurring motif in Sir John Tenniel's work for Punch are ghosts and specters. There are pieces where ghosts appear before the Queen of India, at a railway disaster, or beside a desperate man attempting suicide. Here, in "Germany's Ally," Tenniel gives a ghostly form to the famine plaguing a weeping Paris during the Prussian siege of 1870. Although France lost and became part of the German Empire, French resentment would eventually lead to their participation in World War I.

1. "The Nemesis of Neglect" (1888)

In a piece that filmmaker Guillermo del Toro praised on Twitter as "the fundamental iconography of the Ripper case," Sir John Tenniel breathed life into the phantom plaguing East London that we'd come to know as "Jack the Ripper."

Along with a poem titled "Nemesis of Neglect," Tenniel drew a ghostly phantom stalking London streets. The art debuted on the eve of the "double murders" of Katherine Eddowes and Elizabeth Stride, bodies that would bring the Ripper case up to at least four (some Ripper theorists believe Eddowes/Stride to be victims five and six) and further fuel panic in the area. In the poem, Tenniel writes of "slum's foul air," illustrating the moral decay of the neighborhood that he believed allowed the depraved acts to happen.