35 years ago, RoboCop took on Ronald Reagan — and failed for one macho reason

RoboCop was meant to critique the police-military-industrial complex. What went wrong?

During the 1980s, films like RoboCop, The Terminator, and First Blood projected onto American screens both the ideals embodied in then-President Ronald Reagan’s political platform. It was a dark time in American society, and the popcorn movies of the era reflected it with startling accuracy.

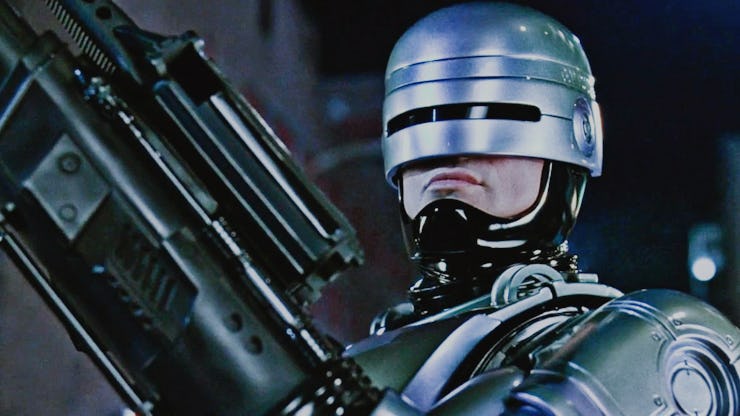

In Paul Verhoeven’s 1987 cult classic, Detroit beat cop Alex Murphy (Peter Weller) ends up an involuntary participant in Omni Consumer Products’ cyborg technology testing after losing his life in the line of duty. He is subjected to extreme body deformities and reconstructions that permanently alter his physique while also attempting to erase his memories.

The film was a response to a time in America in which economic disparity, social apathy, and political fracturing were all increasing. While Verhoven was rightfully critiquing the military-industrial complex that Reagan propelled to the forefront of American politics — and which, to this day, permeates our culture of policing — RoboCop actually reinforced the dominant culture, which honors “masculine strength” as the answer to uncertainty.

And, in the end, Murphy’s cyborg body was hailed as both the new standard and the force that saves the day at the end of the film.

America, after all, loves a hero. We cheer when good conquers evil. Heroes like RoboCop are projections of our collective need for strength in a world that we perceive as violent and ruthless.

But culture also shapes the kinds of heroes we collectively choose, and the heroes we choose can cement our ideas of national unity and identity. Constantly reifying cisgender, heterosexual, toned, white male bodies, then, reinforces that other bodies which don’t fit that paradigm are less than heroic… and less than ideal.

Peter Weller in Robocop.

Susa Jeffords’s 1993 book, Hard Bodies: The Reagan Heroes, explores the idea of which bodies become acceptable — even revered — in society and which are devalued, critiqued, policied, politicized, and easily discarded.

“Hard bodies, heralded by Ronald Reagan, were not just self-images; they were national identities,” Jeffords writes.

Paul Verhoeven's RoboCop was meant to be a critique of the police-military-industrial complex, but he imagined his critique in a hyper-masculine way that ultimately reinforced the idea of authoritarian, hypermasculine policing, and the idea that "masculine strength" is the answer to ending the police-military-industrial complex — as opposed to community and care.

Robocop vs. the ED-209.

Verhoeven, though, was not alone in the era. Terminator and First Blood are obvious critiques of automation and the corruption of the police-military complex, respectively, but both saw the solution as masculine strength. The body ideals seen on screen in these films were reflected in both American legislation and social attitudes.

Jeffords posits that our lack of singular authority in world politics during the Carter presidency — most famously with the taking of hostages at the American embassy in Iran — as well as Carter’s mild (or less “masculine”) manners and less domineering style of politics, triggered the “hard bodies” response.

Hypermasculinity was also a clear response to the perceived lack of economic opportunities for working-class white men and the rush of women into the professional workforce in the ‘70s and 80s (the latter of which was embodied in Verhoeven’s film by RoboCop’s partner, Anne Lewis).

Anne Lewis in Robocop.

Reagan’s failed “trickle-down economics” policy, his harsh policies in the War on Drugs that unfairly targeted Black and brown people, and his refusal to acknowledge the AIDS crisis in a meaningful way for most of his term all targeted what Jeffords calls the “soft-bodies.” To political conservatives, these policies were aimed at “the errant body containing the sexually transmitted disease, immorality, illegal chemicals, laziness, and endangered fetuses,” she writes.

Recently, bodies have again become a political focus. The end of Roe vs. Wade, increasing restrictions on transgender people, efforts to limit education around race and eliminate discussion of LGBT people around children, and crackdowns on petty crime and homelessness have become significant stressors on “soft bodies.”

As conservatives once again target those they see as “soft bodied,” the dominant Marvel films of our era have brought back the aesthetic of masculine “hard” bodies, providing them superpowers and reifying the police-military-industrial complex. Emphasizing the physique of many of the superheroes, some of the actors are even asked to sign contracts that compel them to build and maintain a certain physical form in real life, too.

But both the hard-bodied blockbusters of the ‘80s and the Marvel films of the 21st century are symptoms of a larger, structural problem: that the United States only deals with systemic issues like poverty, violence, economic uncertainty, and other social issues with hypermasculine violence — especially in times of uncertainty.

This article was originally published on