“You’re looking to make things scary and bad.”

'Malignant' explained: What horror gets wrong about imaginary friends

'Malignant' is just the latest in a thriving horror sub-genre devoted to evil imaginary friends. Here's what these movies get right (and wrong) about having an invisible buddy.

by Andy CrumpPsychologists don’t totally agree on how many of the world’s children have imaginary friends, but get enough of them together and they’ll give a ballpark figure.

For invisible friends, the number is 37 percent. For something less ethereal, like a stuffed animal, that percentage jumps up to 65. In other words, if you’re reading this, there’s a pretty good chance that at some point in your young life, you had an imaginary best friend.

But the chances that your imaginary friend goaded you into murder are (hopefully) much lower. And the likelihood that your invisible pal was actually an evil entity bent on harming your real-life friends and family is lower still. If that somehow did happen to you, there’s a pretty good chance it’s because you’re in a horror movie.

There’s a small-but-growing horror subgenre devoted to imaginary friends: Session 9, Hide & Seek, Sinister, The Orphanage, The Conjuring, Daniel Isn’t Real, Z, and most recently Malignant, James Wan’s latest project, where the Aquaman director pours his DC money into 90 minutes of 2000s-era horror parody capped off by 20 minutes of bananatown carnage.

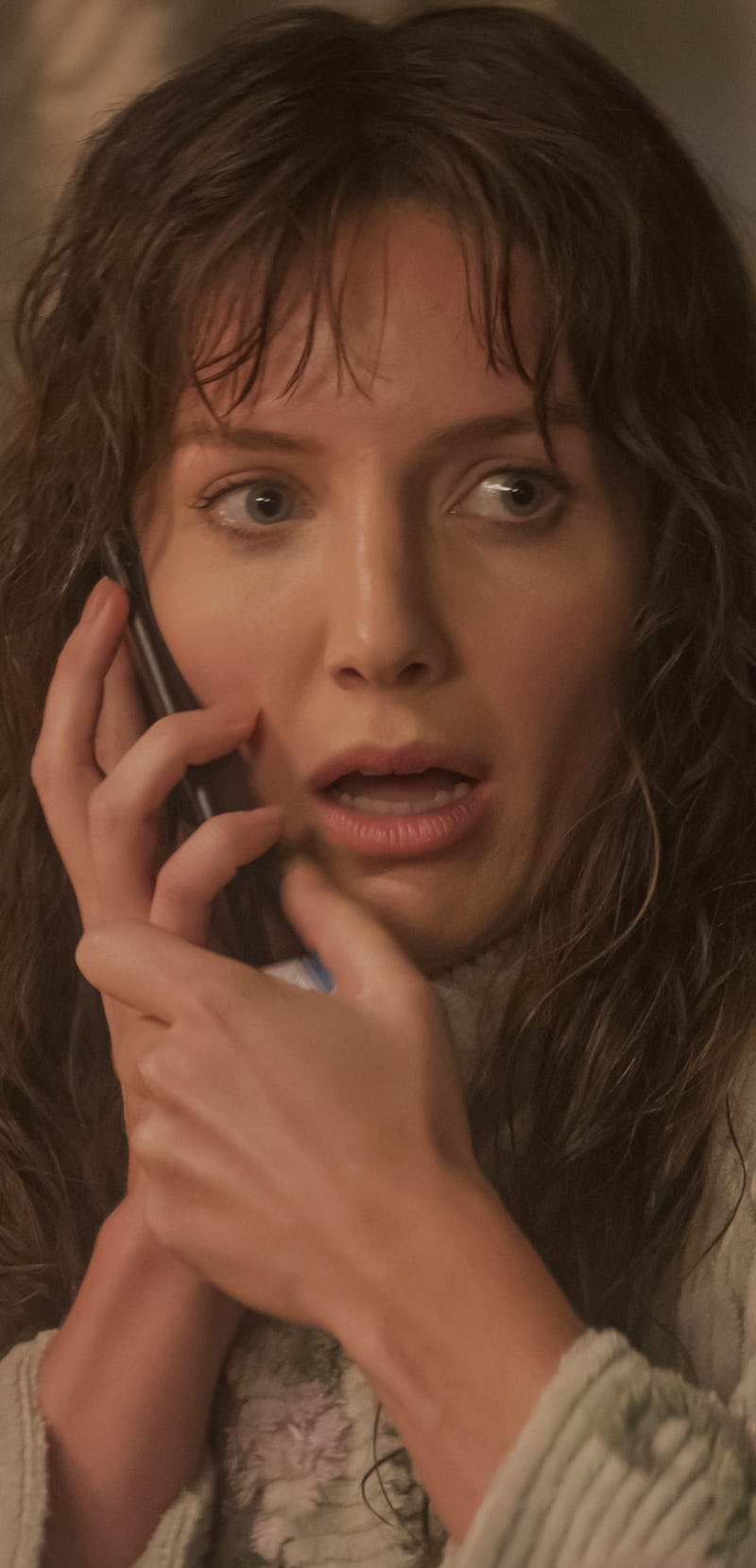

Malignant relies on a boilerplate imaginary friend plot arc where the protagonist, Madison (Annabelle Wallis), becomes the prime suspect behind a rash of gruesome killings that are actually being committed by her childhood imaginary friend, Gabriel.

But buried in Malignant (and every imaginary friend thriller that came before it) is a common misconception about what it means to be a kid who talks to themselves. Here’s how society has evolved beyond horror’s take on this common behavior and why imaginary friends and monsters got mixed up in the first place.

The truth about imaginary friends

Malignant relies on a boilerplate imaginary friend plot.

Evil imaginary friends have captured pop culture’s fascination for a long time, though not as long as people have viewed imaginary friends as a sign that something’s wrong with their children. In decades past, watching your kid play with an imaginary pal — that is, watching them play alone while pretending they’re playing with someone else — was a reason for concern. Over the years, horror films, plus a few non-horror entries like Fight Club and Drop Dead Fred, have reflected that concern by framing imaginary friends as villains. Sometimes the “friend” is a split personality. Sometimes it’s a ghost or a malicious being from another dimension. At all times, they’re wicked.

But that’s the movies. In reality, imaginary friends are misunderstood. In fact, having an imaginary friend is a good sign, not a red flag, says developmental psychologist Marjorie Taylor.

“The stereotype would be a shy child who has trouble making real friends or has problems with fantasy-reality distinctions,” Taylor tells Inverse. “That’s completely incorrect. It’s the exact opposite of that. It tends to be children who are less shy than other children that have lots of real friends. They’re social people who enjoy interacting with others, and they have no problem with the fantasy-reality distinction.”

For kids with imaginary friends, the boundaries are clear. They recognize the keyword “imaginary,” and they know that the unicorn plushie they talk to and have tea parties with is just that.

Psychological research on the value of imaginary friends has become more mainstream of late. Parents used to think of imaginary friends as problematic. Nowadays, they worry if their child doesn’t have an imaginary friend.

“I’ve been asked, ‘Does this mean my child is not creative?’” Taylor says.

Our cultural perspective on what it means to have an imaginary friend has shifted entirely. Children who have invisible playmates tend to be more socially adept, more empathetic, and more resilient, too. That relationship gives them an outlet to process feelings like grief, as in the passing of a loved one. In short, kids with imaginary friends benefit from the experience.

Horror movies and imaginary friends

In Daniel Isn’t Real (2019), Luke’s imaginary best friend returns to help him through college.

So why do horror movies still treat imaginary friends as fiends? With infrequent exceptions — see Syfy anthology series Channel Zero’s 4th season, The Dream Door — an imaginary friend in a movie is a bad omen and a guaranteed gateway to creepy times. But if the psychology is sound and the truth about imaginary friends is so bright, why do we still fear them?

Fortunately, Taylor is not only a seasoned psychologist, she’s well-versed in how pop culture depicts imaginary friends.

“People use them as a way to move the narrative along lots of times,” she says, “because if the child has an imaginary friend or the character has an imaginary friend, they’ll voice their innermost thoughts out loud. You don’t have to have a thought bubble or something.”

Imaginary friends are flexible, too. They’re ambiguous entities and can take all manner of form and visage. Taylor brings up Bing Bong, the imaginary friend in Pixar’s Inside Out, as another positive example outside of the horror genre. He’s a pink cat-elephant-dolphin made of cotton candy, the polar opposite of anything remotely scary.

But on the other end of that spectrum, there’s Daniel, the antagonist of Adam Egypt Mortimer’s 2019 film Daniel Isn’t Real, portrayed in human form by Patrick Schwarzenegger and ultimately revealed as a demonic spirit so indescribably hideous that H.P. Lovecraft would’ve applauded its design.

Mortimer’s answer to the question of “why” expands on Taylor’s.

“It’s such an incredible way to tell a story that we can all identify with about the internal struggles we have as people,” Mortimer tells Inverse. “You want to be a good person, but there are also impulses or voices telling you to do something different. What the imaginary friend idea does is externalize that in a way that becomes a movie.”

Daniel is the imaginary friend of Luke (Miles Robbins), or he was when Luke was a kid. In the film’s present, they’re both grown up, and Daniel’s reemergence comes as a relief to Luke. Daniel helps him with school, his ailing mother, his social life, and, most of all, his love life. But Daniel’s up to nothing good and turns out to be very much real. He’s a devil disguised as an angel, coaxing Luke to be his worst self.

It’s a classic twist in all imaginary friend horror films. The imaginary friend isn’t imaginary at all and only pretends to be a figment of the imagination to cover up some horrible truth. Mortimer’s movie hints at this dynamic in the title. Daniel isn’t real. The eldritch figure posing as Daniel, however, is.

Mortimer recalls his own imaginary friend as “very positive,” again echoing the research Taylor speaks to and how that recollection clangs with the way horror portrays imaginary friends.

“There can sometimes be a tendency in horror where the story becomes unwittingly conservative in a way because you’re looking to make things scary and bad,” he says.

Horror filmmakers risk demonizing otherwise benign concepts by using them as adversaries. It’s even possible the genre’s history with imaginary friends plays a part in how we’ve long perceived them as negative.

What Malignant gets right

“The characters are using the term ‘imaginary friend’ to describe something that's actually so much more horrible than real.”

The distinction made in films like Malignant and Daniel Isn’t Real, where the imaginary friend isn’t imaginary after all, is small but meaningful. Apart from avoiding the creative conservatism that Mortimer refers to, the realization that the imaginary villains in these movies actually do exist means that imaginary friend movies arguably are not about imaginary friends at all. Instead, they’re about human neuroses, given shape by malevolent and intangible figures.

“The characters are using the term ‘imaginary friend’ to describe something that’s actually so much more horrible than real,” Mortimer says. “They sort of wish it was an imaginary friend, but in fact, it’s something other than that.”

If these imaginary friends aren’t imaginary, how could they be good the way that imaginary friends are genuinely good in real life?

None of this is to say that horror should only present imaginary friends in a positive light, of course (though if someone wants to make a horror film about the imaginary friend as a protector, they might be onto something). For Mortimer, the concept of the imaginary friend lets horror express personal struggles that are intrinsic to the human condition.

“How can you tell the difference between an impulse that you feel when you think something bad is happening versus when that’s simply your anxiety?”

Some friends might be imaginary, but emotions aren’t. From existential nightmares like Daniel Isn’t Real to ultra-violent spectacles like Malignant, horror movies give us a lens for distinguishing one from the other.

Malignant is currently in theaters and on HBO Max.

This article was originally published on