Is it a crime to forge a vaccine card? And what’s the penalty for using a fake?

It’s not good.

Schools, businesses, the military, and local governments are requiring proof of vaccination. Yet, unlike the European Union and Australia, which have secure digital proof of vaccination, the United States has not created a systematic way to track vaccinations around the nation. Most places in the U.S. instead rely on paper cards with handwritten notes, which can be easily forged.

As scholars of health law and criminal law, we know that people who forge their own vaccine cards or buy forged cards are already facing criminal charges.

Federal prosecutors have already brought criminal charges against a naturopathic doctor in northern California. In a case involving a licensed pharmacist in Chicago, prosecutors argued that selling official vaccination cards to people who were not really vaccinated effectively stole something from the government, by giving it to others without the government’s permission.

This isn’t an entirely new phenomenon. For many years, it has been a federal crime to make or use “any materially false writing in any matter involving a health care benefit program.”

Why you shouldn’t forge a vaccine card

When people are caught knowingly buying, selling, or using false cards, the proof of guilt will often be clear. The real question is about the appropriate punishment.

Some of the relevant laws, such as wire and mail fraud, have penalties of up to $250,000 and 20 years imprisonment for each email, website visit, call or package sent as part of the scheme. These charges can add up, so that a person who sent an email requesting the card, used Venmo to pay for it, then received it in the mail could face 60 years of imprisonment and $750,000 in fines.

But in practice, the law gives prosecutors and judges huge discretion on how to charge and sentence offenders. Typically, judges consider the degree of harm caused or at least the value of the thing that was wrongly acquired. In the case of forged vaccine cards, that is a thorny question.

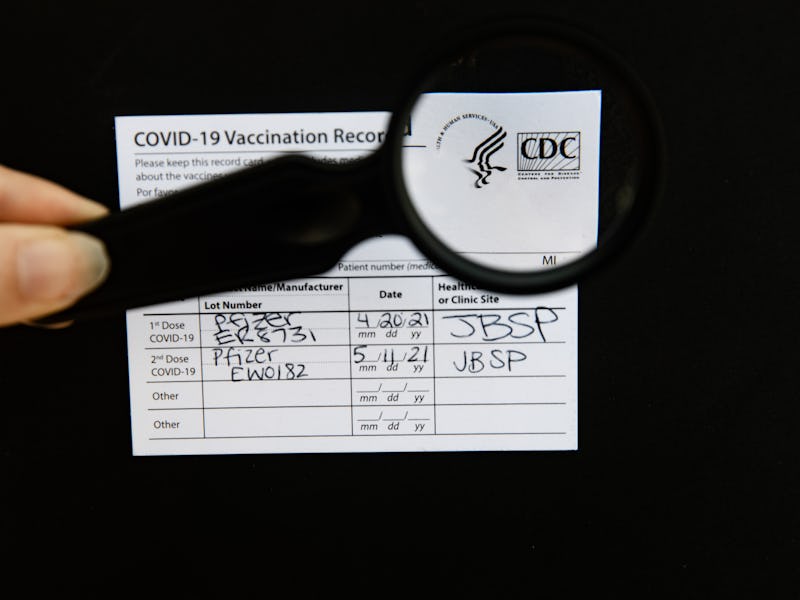

This forged COVID-19 vaccination card was seized during a criminal investigation in California.

A fake vaccination card deceives universities, businesses, and employers into granting access they otherwise would not, letting someone use land, buildings, or equipment they otherwise would be barred from.

In some cases, such as those involving an astronomy researcher supported by federal grants or athletes in bowl games, that access might be worth thousands of dollars. More importantly, that fraudulent access might risk the health of students, clients, and staffers who rely on vaccination policies for their own safety.

Prosecutors don’t need to prove that someone was infected or died as a result of a particular person’s use of a fake vaccine card at a specific place and time. The fake card user’s intent to violate trust is sufficient to make the act a crime.

Why counterfeiting is serious

Aside from the institutions and individuals defrauded, the social harm is obvious. Like counterfeit money or forged checks, a fake vaccination card undermines the public’s faith in all vaccination cards. If a sizable number of documents were illegitimate, people would be unable to trust any of them.

Punishment in money counterfeiting cases, quite logically, often tracks the value of fake currency possessed. In June 2021, two Maryland men were sentenced to 37 months in prison for creating and passing $95,000 in counterfeit bills. But in other cases, the Supreme Court has said that a series of even minor financial frauds, amounting to less than $250 in total losses can lead to life imprisonment.

So far, no one has been sentenced for creating or possessing fake COVID-19 vaccination cards. It is therefore not clear how courts will evaluate the harm done by this sort of fraud.

Nonetheless, whether the harm is conceived as against the government, against the particular people who rely on cards, or against the social trust, it is clear that prosecutors and judges have sizable penalties they can hand down.

This article was originally published on The Conversation by Christopher Robertson and Wesley Oliver at UCL. Read the original article here.

This article was originally published on