A Common Steve Jobs Quote Is Wrong, According to a New Study

In the next few weeks, 4 million graduates will arrive on the job market.

In the next few weeks, something like 4 million graduates will arrive on the job market, according to the National Center for Education Statistics (the figure includes master’s and associate’s degrees). My biggest hope for them is that, by now, they’ve learned how to tell anyone encouraging them to “find their passion” to shove it.

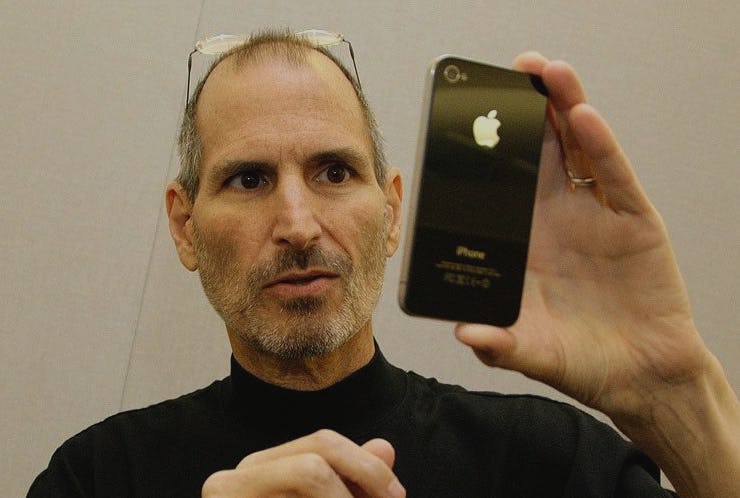

The most high-profile advocate of “finding your passion” is probably Steve Jobs, who made doing what you love the subject of a famous and endlessly reblogged commencement address at Stanford University.

This is an adapted version of our weekly Strategy newsletter, which offers reporting and insights about your career, life, and finances. Sign up for free here.

“You’ve got to find what you love,” reads the transcript of his remarks. “Your work is going to fill a large part of your life, and the only way to be truly satisfied is to do what you believe is great work.”

Jobs is wrong here. And more than that, he’s actually engaging in rhetoric that’s pretty shady and exploitative, at least for a boss, according to a new study from researchers at the Duke Fuqua School of Business. As critic and scholar Miya Tokumitsu noted at the time, workers who are supposed to love their jobs seem more likely to be exploited. The Duke study suggests Tokumitsu is right.

Bonus: I am loving my ingenious colleague Sarah Sloat’s new newsletter about the Sunday scaries, an awesome mix of soothing science, calming advice, and mesmerizing GIFs to prepare you for the week ahead. You can sign up here.

Win Stuff

Do you love your job? Or do you get satisfaction elsewhere? Or vice versa, maybe you had a hobby that you realized could turn into your job? What’s your take on this whole “love your job” thing? Shoot me an email and the best response gets a T-shirt. And thanks to Dawson Barber for his particularly memorable response to last week’s prompt on working from home:

“I spent way too many years commuting two hours a day so I could sit in an office and email people who sat less than 50 feet away from me. In a lifetime of absurdities, that still takes the cake,” he writes. Dawson, shoot me your address and shirt size, and I’ll send you a shirt.

Why You Gotta Detach

As with a lot of things the Apple founder said and did, the “love what you do” mantra was baked into the Silicon Valley ethos. Tim Cook recently said something similar at George Washington University, noting that without a greater purpose, a job was just a job, and that “life is too short for that.” And Paul Graham, another Silicon Valley luminary who helped found the most successful “tech incubator” in the world, made a (admittedly more nuanced but still similar) case on his widely read blog in 2006.

Just as software ate the economy — four of the world’s 10 largest companies are now West Coast-founded tech companies — ideas from these entrepreneurs about the inherent purposefulness of work filtered into other professions as well. Famous career counselors like Richard Leider talked about how to align skills, passions, and values to help you find the perfect career. Eventually, even fast food workers were expected to exhibit passion on the job, reported the London Review of Books in 2013.

There’s a reason why so many bosses have embraced the language of passion work, even for tasks as mundane as assembling breakfast sandwiches.

Jay Kim, the lead author of the recent Duke study, explains that passion-seeking workers are more susceptible to certain kinds of worker exploitation. These include being asked to work extra hours for no pay and doing tasks unrelated to their job.

“There’s a pattern showing that when people see a passionate worker as opposed to a non-passion worker, they think it’s more legitimate to treat the passion worker worse than the non-passion worker,” Kim tells Inverse. “Because you believe this worker is passionate, you legitimize poor treatment of that passion worker.”

This isn’t always such a great injustice. I’m not out here saving lives; I’m out here blogging about things I like. I don’t think it’s necessarily unethical to apply different standards to expecting me to work late (which, in all fairness, may be necessary because I was fucking around on Twitter too much) and asking, say, a school teacher or a home care aide to work late. The problem is, this effect also happens to school teachers.

Why is this? Kim explains that it may have something to do with the human capacity for self-rationalization. People really do need to see the world as being fair even when it’s not. Many studies have found that the more money you have, the more likely you are to believe in American meritocracy (poor people, surprisingly, seem to be more skeptical of this notion!)

Passionate workers aren’t hard to identify. Kim says people do associate certain professions — artistic ones, purpose-seeking jobs like teaching — with being passion-seeking, and, therefore, it being “okay to exploit you a little more.” I think we can see this dynamic at play with teachers in particular. The gap between what a teacher makes teaching and what they could make in another job related to their field hit about 21 percent in 2018, according to the Economic Policy Institute, a record high. Teachers are expected to grade papers in their free time and are expected to cough up personal money for superfluous non-necessities like “books” and “seating.”

Things worked out for Dwight on 'The Office', maybe modern TV's best example of a passionate employee.

To be clear, Kim’s study dealt chiefly with how humans “perceive” passion-seeking workers and plan to take their efforts into the workplace to see how these effects play out in their job. But Kim also says this dynamic can likely be found in all kinds of professions, not just the creative or the do-gooder jobs they are typically associated with. Thinking about this particular type of passion worker, I can’t help but think of The Office’s Dwight Schrute, who, memorably, loves paper and his job so much he sneaks in early to arrange the toys on Michael’s desk and resigns himself to doing his boss’s laundry for a year.

As the story of Dwight eventually showed, being this passionate isn’t always a bad thing. Dwight achieved his dream of becoming a manager, and Kim points to other research which does indeed find that passionate workers are more likely to get promotions. A 2010 study of fashion workers in Milan also found that, for a lot of workers, the glamor and creative fulfillment really did seem compensatory enough to make up for the fact that they were working too much and being underpaid.

The question, then, is: How do we draw lines between being passionate enough to promote but not so passionate that it seems OK to assign you with taking out the office trash? Kim says it’s about balance. Managers also need to be aware that they’re more likely to subject passion-seeking workers to exploitation. After all, the stakes are probably a little higher for them. Grind your most passionate workers too hard, and they’ll leave.

This is an adapted version of our weekly Strategy newsletter, which offers reporting and insights about your career, life, and finances. Sign up for free here.

What I’m Reading This Week

- The US bestows many economic benefits to married couples that single people are denied. Should it be the other way around? In Quartz.

- Miya Tokumitsu also has a great essay about the professionalization of leisure — look at my tasteful, travel-filled Instagram! — in Baffler.

- This award-winning NPR/Center for Public Integrity investigation about how drug companies profit off of Medicaid in CPI.

Leisurology Links

More Strategy

This has been Strategy, a weekly rundown of the most pertinent financial, career, and lifestyle advice you’ll need to live your best life. I’m James Dennin, innovation editor at Inverse. If you’ve got money or career questions you’d like to see answered here, email me at james.dennin@inverse.com — and pass on Strategy with this link!