What the Oregon Militia Can Learn From the Native American Occupation of Alcatraz

A multi-year occupation of a Federal land made huge changes for Native Americans. This new militia occupation should take note of the pathos required.

It’s been seven days since an armed militia overtook an Oregon government building, lead by Ammon Bundy, an anti-government protester who has previously taken up arms against the government to protect the ranch of his father, rancher Cliven Bundy. The group announced its plans to retain control of this facility for up to four years as a form of “peaceful protest,” despite being a group of 150 armed men who have declared they’re prepared to die for their cause. That cause, it seems, includes the protest of the re-sentencing of two local ranchers in an arson case, Islamophobia, and the return of federal lands to private ownership. Whatever the case, one of the members has already taken to social media to call for supplies because the group is already running low. Also, reports of infighting have grown, including today’s announcement of a prominent member drinking his financial donations before bailing.

While there’s a lot of reasons this protest comes off like a disaster, including protesters complaining they cannot attend until their welfare check arrives, what they may be unaware of is a surprisingly successful, multi-year peaceful occupation of federal property just outside of San Francisco.

Last year was my first trip to Alcatraz, which is a surprisingly difficult tour to book. While there, I was surprised by a number of things, including the sheer number of over-priced DVD copies of The Rock available in various gift shops, and overhearing some children on the tour whose parents had never explained the concept of prison to them before bringing them to this unending nightmare of concrete and steel bars.

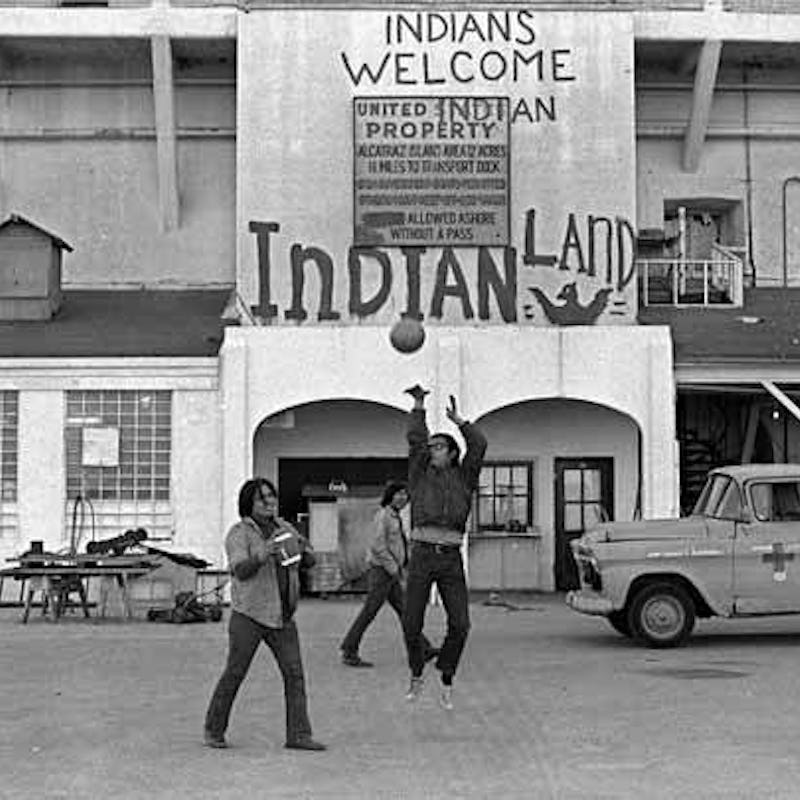

One of the stranger details, completely unmentioned by an element of the tour, was a recurring motif of distracting graffiti, tarnishing some of the largest island landmarks with perplexing phrases. On the boat ride back to the mainland, as a cursory internet search introduced me to the source of these ignored elements, and introduced me to one of my new favorite fascinations in modern American history.

The background is that the “Treaty of Fort Laramie” between the United States and the Lakota Tribe (1868) declared that all retired, abandoned or out-of-use federal land should immediately be returned to the native people from whom it was obtained. Since Alcatraz Penitentiary had been closed on March 21, 1963, and the island had been declared surplus federal property in 1964, a number of “Red Power” activists felt the island qualified for a reclamation. Thus, it gained the attention of IOAT — the Indians of All Tribes protest group.

In March of 1964, a group of Sioux peacefully reclaimed Alcatraz for about four hours, led by a lawyer who represented their interests and a protective layer of journalists and photographers who guaranteed that nothing violent would occur on their watch. This group of 40 Sioux and an almost equal number of journalists combined to make an impressively ironic business pitch: that the Native Americans should be able to reclaim this property at the same price the federal government originally paid for it. At 47 cents per acre, this amounted to $9.40 for the entire rocky island, or $5.64 for the 12 usable acres. The event was shut down quickly, and dismissed in the press as a piece of political theater.

Then, in November of 1969, a small group of Native American University of California, Berkeley students chartered a yacht to get them near Alcatraz, then jumped overboard. They swam to the island and claimed Alcatraz by Tera nullis — a right of discovery which allows the possession of a no-man’s land. Again, Alcatraz was only in operation from 1933 until 1963, due to the difficulty of maintaining a prison that needed constant resupplies. Unfortunately, the Coast Guard refused to allow this succession of land despite a nearly 100-year-old federal mandate. They rounded up the protesters and took them back to land. Through sheer determination, the protestors found their way back onto Alcatraz before nightfall, and were removed a second time the next morning.

These events set the foundation for something much bigger, just a few weeks later.

On November 20th, 1969 in the early morning, 90 American Indians, including married couples and children deliberately and publicly set out to reoccupy Alcatraz Island. Again, the Coast Guard managed to prevent most of the protesters from making the trek, but a minor 14 individuals managed to make land on the abandoned island.

Thus began the Occupation Of Alcatraz.

This initial group of 14 Native Americans would provide a foothold, that would lead the island to being occupied from November 20th, 1969 until 19 months later, when the protest ended peacefully. At its height, as many as 400 protesters would be on the island at the same time. Once the Coast Guard stopped fighting the independent boat trips to Alcatraz, a system of constantly replenishing supplies and alternating duty took hold, and the occupation could have lasted much longer than it did.

Doris Purdy, an employee of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, made a single night trip out to the island and made this film, which her children have made available online.

The initial group demanded control of Alcatraz so it could develop several Indian institutions, such as a center of Native American studies, a spiritual center, and a museum, partly as replacements for a San Francisco Indian center that had burned down. The Secretary of the Interior had actually introduced the idea of converting Alcatraz to replace this lost facility, but after there was no progress on this promise, the Red Power protesters carried the idea forward. Another motive for the occupation was the government’s general treatment of Indians. The government 16 years earlier had begun a policy of terminating Indian reservations and relocating the inhabitants to urban areas. Obviously, taking back a well-known yet unused location would be a victory on several levels.

The first three days of occupation were met by serious defense by the Coast Guard, but by day four they were recalled due to public outcry because San Francisco had a sense of humor. Literally. The San Francisco-based writer Fortune Eagle served as spokesman for the group, and sent frequent updates to the local media that were not only effective and universal in their language, but also drenched in a satirical comedic voice that the Bay Area universally championed. This led to city-wide calls for supplies, that San Francisco responded to with overwhelming support. Yes, a little bit of charm and a healthy dose of social justice made a peaceful occupation of a government facility into the cause of the year. Years later, it would come out that the FBI had a plan in place to retake the island, but that President Nixon demanded they stand down when he saw that public support was on their side.

The 400 strong height of presence was organized, hilariously, for the night of Thanksgiving, 1969. According to CNN, actor Benjamin Bratt was among those in attendance. One of the co-stars of Demolition Man once occupied Alcatraz as a child. We’re all on board as to how insane this is, right?

In the early 1970, things in the occupation began to turn dark. A child fell to her death on the island, and a number of politically-minded hippies from San Francisco started trying to be “good allies” on the island, until a rule was passed that non-Native Americans were not allowed to stay overnight — born of a sudden influx of drug addicts that were using prison island Alcatraz as cover.

While the group maintained control of the island, public attention waned. Supplies, push, and political importance dwindled throughout 1971. The government noticed the opening and began to cut services, including electricity, phones, and fresh water for the island. On the 11th of June, 19 months in, a gigantic federal force moved onto the island, when the controlling presence had reached an embarrassing low of 15 members. It was a quick, pleasant exchange that brought an inspiring resolution to an event that could’ve ended in unnecessary bloodshed.

The Occupation of Alcatraz became the modern standard of peaceful protest, and remains the highlight of Native American defiance. It spawned a recurring celebration of remembrance called Unthanksgiving Day and several other nationwide events, but more importantly influenced the American government’s decision to begin making federal grants to tribes on par with changes previously introduced by the Civil Rights Movement. Richard Nixon himself made tremendous pushes for Indian rights in the middle of his presidency, and was outspokenly frustrated by the bureaucracy that prevented him from enacting more extensive changes.

So when you spend the next couple weeks watching a childish group of reactionaries make claims about their willingness to die in federal gunfire on behalf of an undefined set of virtues, remember the Native American protesters who claimed the Rock and held claim through a supportive culture for almost two years, making their point peacefully as well as effectively.