Four Elements Are About to Get Names on the Periodic Table

Ununtrium by literally any other name is much better.

Four elements are about to get official names — which, if you care about chemistry, is tremendously exciting because 1) the bottom period of the periodic table will be complete and 2) names, as any wizard could tell you, have power.

The International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry — IUPAC, which is sort of the U.N. of the periodic table — announced late Wednesday that research into elements 113, 115, 117, and 118 officially fulfill the naming criteria. Scientists have polished off the bottom-most row of known elements, making these the first to get names since livermorium in 2000. The Japanese chemistry consortium RIKEN is particularly stoked, as IUPAC, along with the International Union of Pure and Applied Physics, is crediting Japan with the sole discovery of element 113.

It’s very rare that four elements are confirmed and validated around the same time, IUPAC’s Executive Director Lynn Soby tells Inverse. Rare — but not quite a coincidence. Few labs have the equipment necessary for glimpsing heretofore unknown elements. “It’s not like anybody and their brother could find one,” Soby says. “You need a supercollider and a lot of physicists involved.”

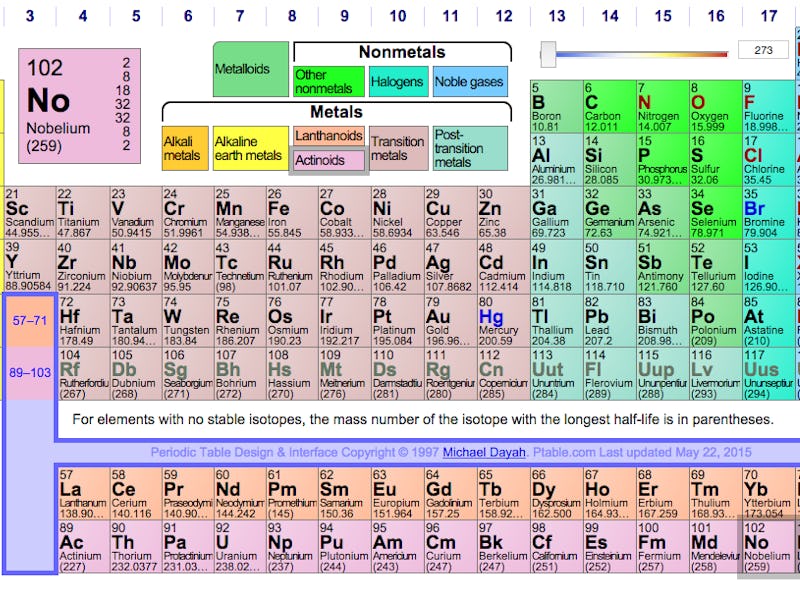

IUPAC's periodic table, in need of a post-December 2015 update.

Discovering a new, super-heavy element (they’re all heavy from here on out) requires analysis of a radioactive substance that does not exist outside of laboratories; even then, the heavies are unstable and last only on the order of milliseconds, until the elements rocket subatomic particles out of their nuclei and become more familiar isotopes like roentgenium. Each of the new elements has a unique, measurably identified atomic weight, and getting to this phase of their scientific history caps off decades of research.

Until now, the elements have gone by either their atomic weights (the numbers) or placeholder names based on their order: ununtrium, ununpentium, ununseptium, and ununoctium. Along the way, they’ve collected various other nomenclatures — ununoctium has been called eka-radon, following in Dmitri Mendeleev’s tradition of naming predicted but undiscovered elements, because it sits underneath the noble gas radon.

The bizarre names are very much only placeholders. Japan will get to propose a name for element 113; in the case of the other elements, Russia’s Joint Institute for Nuclear Research and the American Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (for 115, 117, and 118) plus Oak Ridge National Laboratory (115 and 117) will get to jointly propose names. The final decision, however, rests with IUPAC. And civilian chumps like us? “The general public does not get involved in the naming of elements, however much they’d like to be,” Soby says.

Still, even as spectators, it’s a chance to witness chemical history — not something that happens all that often. “The elements are very important for everything we do,” Soby says, “and everything we are.” Does she envision another naming opportunity rolling around anytime soon? It’s an important question — tied up in the bigger question of, as Soby notes, “What do you do when the periodic table ends?” — but the odds don’t look great for answering it tomorrow. “Probably not in many years — that is so far away from where we’re at today for 119.”