How Quitting Your Job Affects the Wiring of Your Brain

Different minds tolerate and embrace risk differently, but big changes precipitated big changes.

The United States is big on quiet desperation: Polling suggests that less than one-third of Americans are enthusiastic and committed to their work. As the recession wanes, more and more of those people are ditching bad gigs and hitting the open market — even though research shows that’s probably ill advised without the next thing lined up.

We celebrate the extravagant quitters in real life and in fiction: They are the Jerry Maguires and the JetBlue stewards who are done with this bullshit. We celebrate these people. But the visceral satisfaction of the walk out is foreign to the less emotional parts of the human mind. Your brain doesn’t take major risks lightly because that’s not how it was wired.

Context-free decision making does not exist — your perception of events, biases of memory, and cognitive consistency deeply affect how you make a choice. When a risk like “I quit” emerges, you subconsciously consider it on two levels. The process you’re probably acutely aware of is described by researchers from Kaiser Permanente and the University of Oregon as “risk as feelings” — a fast and instinctive reaction to danger. The other mode is “risk as analysis,” which is more deliberative, but doesn’t always happen cost-benefit list style. Your brain’s rational system is constantly trying to balance these impulses in the form of a decision. You are, in short, a committee.

But the chances that one will actually make a risky choice is very much determinant on the individual. When you consider making a gamble, how your brain operates determines whether you go for it.

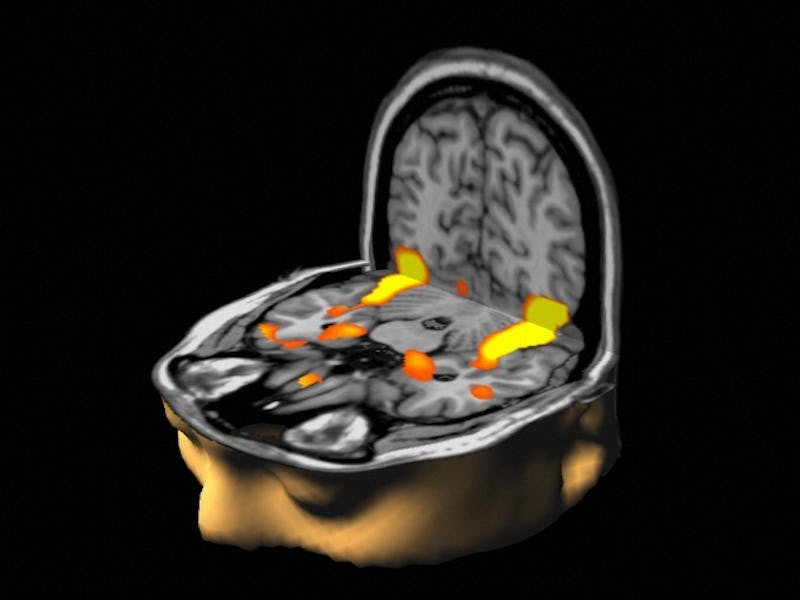

“Individual differences in brain activity correspond very closely to individual differences in participants’ actual choices,” said University of California, Los Angeles professor Craig Fox in a statement discussing his research.

“The people who show much more neural sensitivity to losses relative to gains are the same people who are very reluctant to gamble unless they are offered extremely favorable gambles. The people who are about as sensitive to losses as gains neurologically are the ones who are more willing to gamble.”

Essentially, if someone has more brain activity happening in their prefrontal cortex and ventral striatum when they are considering making a decision that can offer big rewards, they’re less likely to take the risk. If the person is more deactivated in their cognitive reward pathways, they’ll take the plunge.

Differences in brain wiring aren’t the only variant when it comes to decision making. Our genes determine our reactions as well. Research has found that decisions are influenced by the the amount of dopamine-regulating genes people have. People who have a particular variation of a dopamine receipting gene are more likely to be risk-takers; it’s a neurotransmitter that is eager to streamline the feelings of pleasure and gratification.

To be expected, what stresses our brains out the most is when we have to make a decision that offers positive and negative effects — like an amazing job offer that’s located in a city far from your friends and family. But while stress may permeate all of the decision making process when it comes to quitting — your job stresses you out; the thought of leaving stresses you out even more — it’s actually not conducive to leaving your work. Chronic stress actually biases people to stick with what they know — they default to whatever their habits are. But this default to stay with your schedule is reversible when the stress is gone — meaning if you really want to quit your job, you’ll need to remind yourself why that’s so when things calm down.

The good news is that when the time comes to actually make the decision, your brain is your best cheerleader. A study published in Psychological Science determined that people have the tendency to rationalize events in a way that spins them in their best interest. If you quit, the mechanisms of your brain will trigger you to think of all the reasons why that was the best choice. If you don’t, you’re likely to reframe the situation to why that’s a fine decision.

If you do decide to opt into “strategic quitting” be conscious of two things: People often don’t realize how toxic a workplace was until after they leave it and… unemployment leads to its’ own assortment of psychological ills.

If the neuromechanisms of quitting a job are intriguing, the neurological effects of not having one are just a total bummer.