Why Netflix's 'Making a Murderer' Is Better Than 'The Jinx'

Netflix's new ten-part true-crime series about the Steven Avery murder case is engaging, poignant, and worth the ten-hour-plus time commitment.

“Murder is hot, that’s what everyone wants … and we’re trying to beat out the other networks to get that perfect murder story.” This is a quote from a brief interview with a beaming mid-‘00s Dateline producer in Netflix’s recent original 10-part series Making a Murderer. The producer comments, with eerie transparency, on why the 2005 Steven Avery murder case — the subject of the Murderer series — was “a perfect Dateline story.”

The line feels almost like discomfiting meta-commentary. After all, Making a Murderer — a true-crime saga revolving around the untold story of Steven Avery’s highly contested 2005 trial for the murder of Teresa Halbach — comes hot on the heels of the vast success of similar prestige-y, close-look true-crime programming like the Serial podcast and HBO’s recent six-part reassessment of the Robert Durst murder case The Jinx.

However, the documentarians behind the Netflix series — Moira Demos and Laura Ricciardi — began production a year and a half prior to the trial in 2005, while still finishing graduate film studies at Columbia. The project was intended to be a single film before becoming too unwieldy. Also, they optioned their work to Netflix as a series in 2013, prior to the burgeoning true crime craze of today. So the initial impression of vague opportunism one feels from the Making a Murderer elevator pitch is largely unfounded, though the scope and marketing budget for the project doubtless expanded as a result of the mini-trend.

Too many comparisons between Making a Murderer and those popular projects would be unfair. Avery’s story is very different, wide-ranging and arguably even more fascinating than the cases reopened by Sarah Koenig and Andrew Jarecki. The bizarre context for the Halbach murder case was that Avery had previously been in jail for 18 years for a crime he didn’t commit — the rape and assault of Penny Beernsten. After the case was reopened, the crime was pinned on serial rapist Gregory Allen using a DNA sample, a culprit that law enforcement had overlooked as a potential suspect. Many considered the lack of investigation of Allen to have been the result of a conspiracy against Avery on the part of the sheriff’s department of Avery and Allen’s hometown — Manitowoc, Wisconsin.

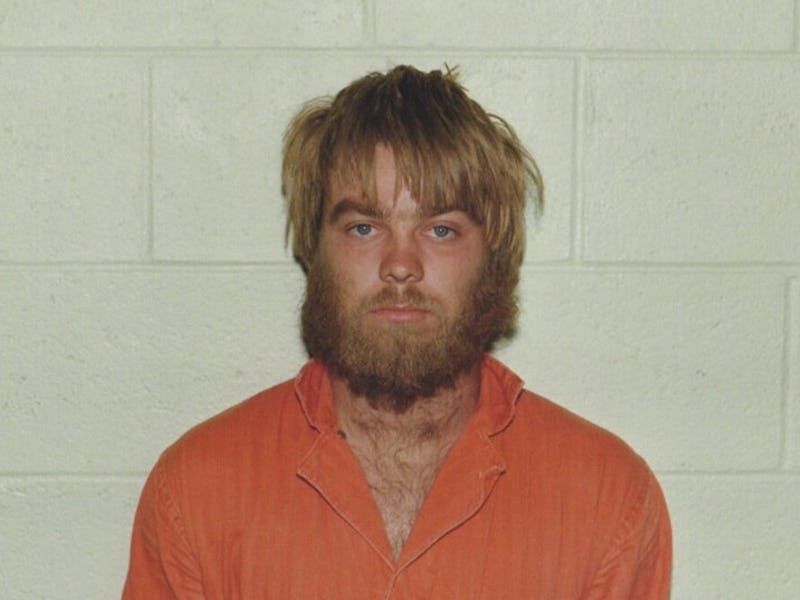

Steven Avery's 1985 mugshot

The ten-part-series — in which every installment runs between 55 to 70 minutes — may seem like a daunting prospect, if Serial and The Jinx burned you out on headache-inducing, often demoralizing programming of this sort. Yet there is more than enough material here to justify the length, both in terms of plot and themes. Making a Murderer’s complicated framework makes for about four times as many fascinating players as become relevant in Serial, and at least twice those of The Jinx. The docu-series gets endless mileage out of the unusual access its filmmakers had: Much of the series is taken up with carefully edited videos from the lengthy Avery trial, as well as tapings of private police interrogations and confessions from throughout a twenty-five year period. This is on top of the hard work that Demos and Riccardi did in Manitowoc, where they lived on and off for years in the interest of making themselves available to capture new events, and follow the defense team and the Avery family closely.

In Murderer, the echoes of apparent collusion against a suspect by law enforcement that ran through Serial — and even more so, the recent, more legalese-y spinoff for superfans Undisclosed — are magnified ten-fold. Avery lived his entire life in a small town, and made enemies in the sheriff’s department. Many of these officials were open about their dislike of Avery; one was even distantly related to him. Even when it became clear that there were major problems with the way Manitowoc police handled the investigation of Avery’s 1985 rape case — and that many of these officials were still active — these shady lieutenants, detectives, and sheriffs haunted the crime scene during the 2005 murder investigation, though jurisdiction had been moved to a neighboring county’s police department.

As a result, threads of placing, tampering with evidence, and most of all, leading a very powerful witness — which spins off into a whole separate trial — come to the forefront on the show, as well as in the media during the time of the case.

In addition to added layers of intrigue like these, the show’s most powerful element is the many obscure psychologies it attempts to excavate. Noah Hawley’s fictional Fargo show — and the Coen’s movie — fixates on the odd mannerisms of lifelong inhabitants of remote parts of the icy Midwest, which sometimes seem to function on their own obscure logic. A set of deeply ingrained, sometimes contradictory Protestant values seem to presage their actions; their inscrutability adds to the drama. In Making a Murderer — which covers a similar, if more disenfranchised, region — very real people seem to constantly be covering up similarly unconscionable things with similar poker faces.

The uncomfortable uncertainty is manifested in action-packed verité here, where it lurks in the shadows of heavy speculation in Serial. Whether it’s the stoic, determined, and reclusive members of the Avery clan, the distinctly smarmy public face of the prosecution, or the thug-like investigators who descend upon unsuspecting witnesses without a lawyer, this is one of the most compelling casts in a docudrama in some years. If you thought Durst was weird and captivating, you’ve got at least ten personalities that are as uncanny and oddly magnetic as him in Murderer.

Making a Murderer is an important show, not simply because it is such a riveting narrative — packed with evidence of gross misconduct on the part of law enforcement — but because of the larger points it makes. The series, much more so than Serial or The Jinx, is an in-depth courtroom drama. Avery’s story is an extreme case study illustrating how impoverished and uneducated people become casualties of a system that is implicitly stacked against them. Again — as Serial’s first season did so powerfully — Demos and Riccardi’s series asks, as Avery defense lawyer Dean Strang puts it: “Do we err on the side of depriving of a human being liberty … when we’re uncertain, as we almost always are?”

As a series, Making a Murderer does little in the way of trying to subvert the conventions of its genre — sometimes its faux-lonesome-folk soundtrack and setups can be heavy-handed. But the medium — as with most documentaries — is not really the message; Steven Avery’s story didn’t require an Errol Morris or Werner Herzog. The world and people of Manitowoc just explode off the screen, drawing one in instantly and stirring deep thoughts and emotions as Steven Avery’s fate becomes ever more uncertain.