Facewatch and CISA Point to a Ravenous, Crowdsourced Surveillance State

New software is making it easier than ever to spy on our neighbors, but those databases are rife with potential for abuse

Two recent developments in surveillance will make it harder than ever to maintain digital and physical privacy. They could also signal a new stage of cooperation between governments, corporations, and private citizens as partners in spying. In short, don’t read this if you get paranoid easily.

On Friday, President Barack Obama signed into law a massive spending bill that includes new spying powers for the government and corporations. Attached to the must-pass budget legislation was the Cybersecurity Information Sharing Act, which allows tech companies to pass user information to the federal government under the guise of preventing cyber attacks.

Critics say the law won’t do anything to secure vulnerable networks, but will drastically expand the government’s surveillance powers. For one, CISA gives seven agencies – including the NSA – broad access to personal information collected by online companies without requiring a warrant. The bill had previously failed on its own, but once House Speaker Paul Ryan announced CISA would be included in the trillion-dollar omnibus bill its passage was all but guaranteed.

“CISA is the new Patriot Act,” Evan Greer, Fight for the Future’s campaign director, said in a statement. “It’s a bill that was born out of a climate of fear and passed quickly and quietly using a broken and nontransparent process.”

We are already living in the “golden age of surveillance,” according to Peter Swire, who served on Obama’s Review Group on Intelligence and Communications Technology. With CISA on the books, that’s truer than ever.

But it’s not just Big Brother who’s spying.

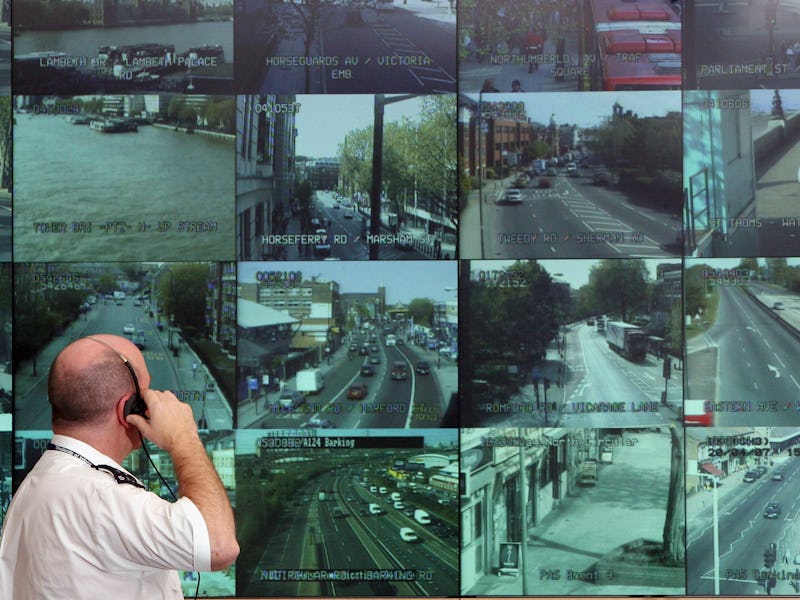

A company in the UK called Facewatch has developed a way to crowdsource a watchlist that allows shop owners and restaurant managers in Britain to share CCTV footage to identify shoplifters or others deemed undesirable. In what was probably an inevitable if unsettling development, users can now integrate the software with facial recognition technology. In theory, that means that if a thief who stole from Store A shows up at Store B, Store B’s manager will get an automatic alert and take whatever action he or she chooses.

The reality may be shadier. As others have noted, there’s a strong whiff of Minority Report-style pre-crime at play here. You don’t need to be convicted of a crime, or even accused, for someone to tag you as a Facewatch “person of interest.” Or maybe you shoplifted years ago — perhaps even committed a violent crime — but did your time. Will a database with a long memory prevent you from buying a sweater?

I’ve covered this topic before, though in a slightly different way. A company called FST Biometrics offers a product that combines facial recognition with full-body identifiers – like height, shape, and gait – to improve the software’s accuracy. In one promotional video, they tout the program’s ability to alert store managers when a VIP customer enters their store.

Facewatch takes an old idea – neighborhood watch programs – and combines it with the most powerful surveillance technology ever created. The company’s website makes clear that its roughly 10,000 clients work closely with police and prosecutors in investigating and preventing crime.

Crowdsourcing isn’t limited to faces, either. Anyone with a computer, an internet-enabled camera, and a few spare minutes can set up an automated license plate reader, courtesy of OpenALPR. “Every time someone drives past one of your cameras, OpenALPR records it to a database,” the company’s website reads. “With a simple search, you can see the full history of a vehicle as it drives through your property.”

One of the company’s two founders told ArsTechnica earlier this year that part of his motivation for developing the software was to eliminate the government’s monopoly on LPRs. “I’m a big privacy advocate as well — now you’ve got LPR just in the hands of the government, which isn’t a good thing,” he told Ars. “This brings costs down.” The post also quotes several privacy advocates who say that for now, at least, creating open-source license plate databases is perfectly legal. But as the article asks: “How long until a license plate reader data blackmail-style website appears?”

Any watchlist that doesn’t have due process protections creates problems, whether that list is maintained by a government or private actors. Governments, in theory, provide at least some recourse to being blacklisted, through the court system. In the U.S., some people wrongly put on the government’s No Fly List have successfully sued to be removed, but thousands remain on it with no way to get off. How many people are in Facewatch’s database without their knowledge, and with no recourse whatsoever?

Laws like CISA will continue to break down barriers between privately collected data and governments who will seek to exploit it in the name of cybersecurity or terrorism prevention. With leading GOP presidential candidate Donald Trump floating the idea of creating a database of American Muslims, limitless surveillance powers should make everybody a little bit paranoid.