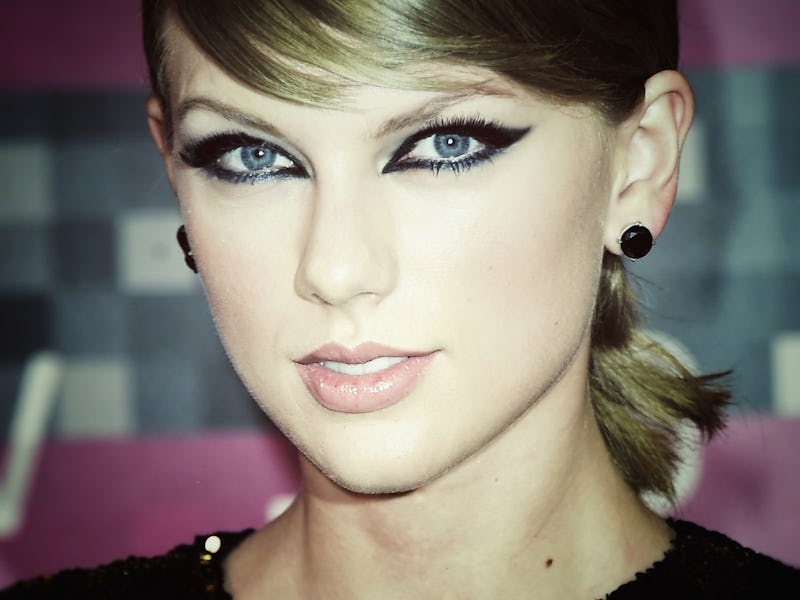

Why Taylor Swift's Donation to the Seattle Symphony Matters for the Future of Classical Music

Orchestras and modern classical composers like John Luther Adams desperately need the Taylor Swifts of the world.

Does your hometown orchestra have its own personal Taylor Swift? Probably not.

It seems Swift, one of the world’s most beloved pop stars, may be beginning to make classical music philanthropy a habit. The first signs came in 2013 when she made a $100,000 donation to her struggling hometown orchestra — the Nashville Symphony — which was one of three major national orchestras to suffer seriously debilitating financial difficulties that brought proceedings to a standstill in 2013. Swift’s second venture was announced today: a gift to the Seattle Symphony of $50,000.

While the Nashville gift made sense as a desperate-times, hometown sort of thing, the rub here is more perplexing: Apparently, Swift’s gift was inspired by the symphony’s recording of an glacial, atmospheric new work commissioned from avant-garde classical music icon John Luther Adams, Become Ocean last year. From a star like Swift, this kind of acknowledgement of movements in the avant-classical world is pretty unprecedented. Then again this must be the year for it: 2015 saw Kanye repping for Pulitzer Prize-winning composer, vocalist, and violinist Caroline Shaw during recent performances of tracks from his 808s and Heartbreak album.

In commenting on the anomalous Swift/Luther Adams connection, The New York Times didn’t venture to infer the fact that Seattle’s recording won both a Pulitzer Prize and the Grammy for best contemporary classical composition last year probably led to Taylor jamming it. I’m not being presumptive or snobby here: It’s fantastic that Taylor enjoys Adams’ music. He’s one of the greatest living and thriving classical composers, with a refreshing, original style. It’s very generous of her to bestow the Seattle Symphony with that amount of money. But it’s important to keep in mind that Seattle has an unusually high budget and level of exposure. Very few smaller national orchestras (most of them) have nowhere near the budget to run anything like a in-house label (18-time Grammy nominated) and can’t risk programming anything outside of 19th century classics like Beethoven and Brahms in concerts for fear of losing the box office. It’s rare for any major metropolitan orchestra to make a profit in the box office playing works by living composers, even if it’s someone with the reputation of John Luther Adams.

With orchestras, one should not assume a cream-rises-to-the-top situation when figuring out where to direct your donations. There are lots of excellent groups out there in constant danger of being extinguished, as groups like the Delaware, Syracuse, and Albuquerque Symphony already have been — and as the ranks dwindle, this means fewer larger-scale and daring works by living composers will have anyone to perform them properly.

Multiple major orchestras cut back operations or close every year in this country. At this rate, it’s unlikely that in a decade or two there will even be major recordings of new, vanguard orchestral music to listen to, or orchestras to play them. During a time when even the wealthiest artistic institution in the country — the Metropolitan Opera — is struggling, the occasion of Swift’s donation is bittersweet. There are a lot of very rich people, but increasingly, with newer generations rising to prominence, hallowed musical institutions are not where the donations are going. The days are numbered for almost any of the local groups that one took for granted growing up.

It’s a sad situation that, for instance, New York City arts organizations run on the dime of multimillionaires like the Koch Brothers — in fact, the petulant refusal of David Koch, among other a limited pool of other donors, to help bail out a bankrupt New York City Opera helped assure the company’s permanent shutdown two years ago. One wishes there were a few more Taylor Swifts — wealthy entertainers who actually cared about art, and understood the need to keep new works alive. It’s not just that these donations help musicians get paid; they ensure the continuing existence of the genre.