How Much Should We Care About 'Star Wars: Force Awakens' Spoilers?

Informed consent may not by a passing craze, but surprise is definitely not the mother of pleasure.

One of the first presents University of Basel philosopher and bioethicist David Martin Shaw let his infant son read was a cartoon book titled Darth Vader and Son, a whimsical tale of Vader caring for toddler Luke. The reason for the gift was twofold:

1) David Martin Shaw likes Star Wars, and 2) David Martin Shaw, who spends the majority of his brainpower tackling thorny issues like euthanasia, stem cell research, and cloning, is fascinated by spoilers.

“I got it away from him once I realized he was going to start remembering it,” Shaw says of the book. “This is going to make me sound like a psychopath, but sometimes when I’m in the cinema, if a trailer comes on and I want to remain unspoiled, I’ll close my eyes, put my fingers in my ears and hum to myself gently.”

Shaw, who is — again — a philosopher, is of the mind that spoilers are inherently unethical. Sure, spoiling a show is a minor crime, but spoiling it on the internet is a minor crime perpetrated in perpetuity. This is the utilitarian position he staked out in a 2011 paper in the journal Ethical Space. “Most people I speak to get the impression I’m being quite precious about it,” says Shaw. “But I don’t care because I know I’m right.”

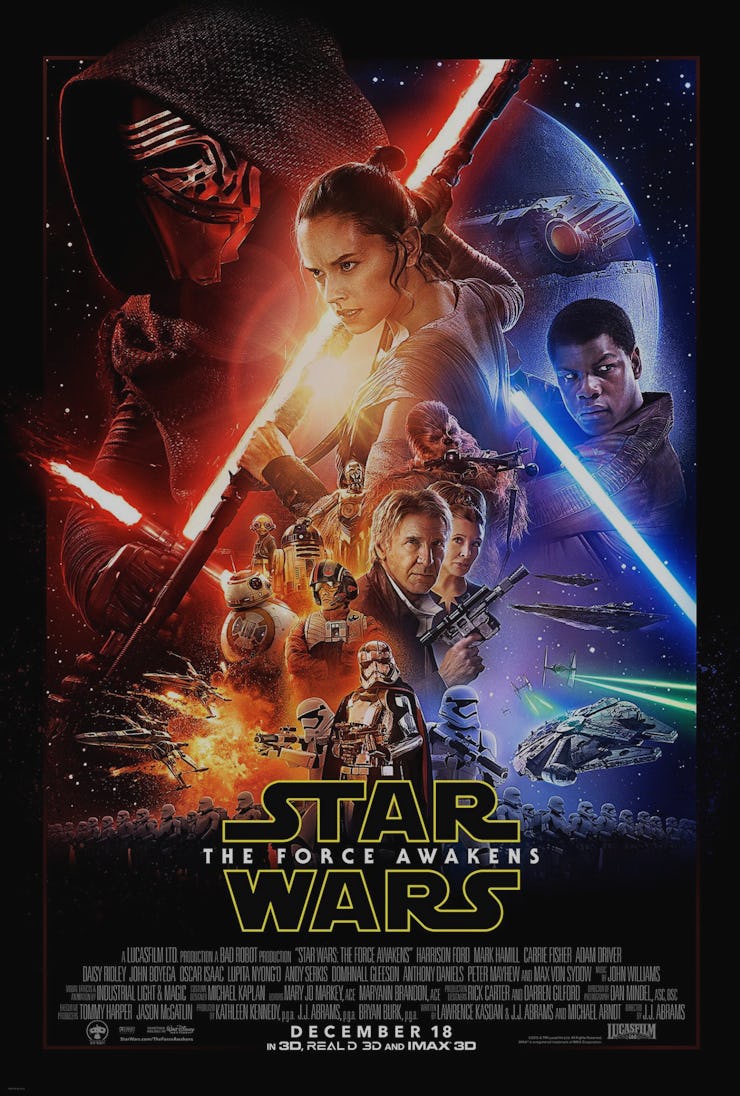

Well, he is and he isn’t. Plenty of people loathe spoilers and millions cried foul when J.J. Abrams compared the new Force Awakens Starkiller Base, which is prominently featured on movie posters, to the OG Death Star. Their not unreasonable complaint is that spoilers steal fun from viewers and fans. The truth is more complicated, because they sometimes do and they sometimes don’t.

The same year Shaw published his paper, Jonathan Leavitt and Nicholas Christenfeld, two psychologists at the University of California, San Diego, wrote a lightning-rod study in Psychological Science demonstrating that knowing the ending of Agatha Christie and Roald Dahl short stories didn’t make reading them less pleasurable. “Plots are just excuses for great writing,” Christenfeld explained at the time. The counterintuitive findings were the pop psychology equivalent of sacking the quarterback, leading writers like Jonah Lehrer to declare: “Spoilers Don’t Spoil Anything.” That was, like many things Lehrer has said, almost true.

We enjoy our stories spoiled, via Leavitt and Christenfeld 2011.

In a series of follow-up experiments to the UCSD research, VU Amsterdam University communication scientist Benjamin Johnson and Albany State University’s Judith Rosenbaum took the spoiled short story concept and peeled it apart. Initially, Johnson tells Inverse, this duo found the opposite of what Leavitt and Christenfeld discovered: Spoilers were harmful. “People had less suspense, people had less fun. People felt less moved when the story was spoiled.” In an attempt to reconcile the contradictory findings, they wound up honing in on personality type.

In 2015, they published a report in Psychology of Popular Media in which 368 volunteers read short stories after reading a spoiled or spoiler-free preview. Johnson and Rosenbaum analyzed volunteers’ personality type, enjoyment of the story, and whether or not the preview made them want to read the story. Based on the study, they concluded that people low on need for cognition actually preferred to read spoiled stories — this could explain the results that Leavitt and Christenfeld found. But don’t confuse need for cognition with IQ or intelligence. “People low on need for cognition — it’s not that that they’re not smart. They often make quick decisions or they rely on instinct. They don’t feel like they have to reflect on everything.”

On the other hand, deeply emotional people didn’t like spoilers. Their decrease in enjoyment wasn’t severe (an average rating of 4.3 unspoiled fell to an average of 3.8 spoiled, on a scale of 1 to 7) but it was evident. “To those people, spoilers are bad,” Johnson says. “They’re probably right to be upset about Star Wars spoilers, because they want to have a roller-coaster ride of emotions when they go see Episode VII.”

It’s unclear how much fandom plays a role, but Johnson has a hunch that we might approach franchises differently. Plus, most of the studies to date have been with short stories, which don’t necessarily inspire the fervor of big-name cinematic universes. In a yet unpublished study, Johnson used clips of popular shows and movies— Game of Thrones, Captain America, Broadchurch. “We don’t have definite results yet,” says Johnson, “but we thought we might see some big effects if we used TV and film, and it’s not necessarily the case.”

Shaw, for his part, argues that when Inverse spoiled Doctor Who for him with the headline “Goodbye Clara,” it robbed him of the choice not to know. “Coming from medical ethics, there’s the concept of informed consent — obviously, the medical comparison is a bit strained — but you have to give the patient information that they have to make a choice.”

So where do we draw the line on spoiler alerts? (Shaw’s rule of thumb used to be that if it was in the trailer it’s fair game, though he is wary of how much more recent trailers give away.) The phenomenon of spoilers is older than America Online — in April 1971 National Lampoon magazine trolled its readers with four pages of fake spoilers — but the internet model of media criticism and dispersal has magnified the debate. Should, say, Jizz in My Pants come with a spoiler alert for The Sixth Sense? Or is there a statute of cultural limitations we can adhere to?

From Shaw’s perspective that second question wreaks of ageism. There’s always a new audience that doesn’t know that Bruce Willis is dead (sorry, not sorry). This point is impossible to argue with, but also problematic for cultural commentators who need shorthand and understand to create meaning without a page of footnotes for every paragraph of thoughts.

Compounding the issue is the expansive and interconnected cinema universe. When reading about Jessica Jones, is there an expectation you should be warned about potential spoilers that could impact Daredevil, Agents of Shield, or the Marvel galaxy writ large? And, if Netflix dumps a season at a time online, as it did with Jones, should you expect that a discussion of the show includes references to moments throughout the entire season?

Johnson doesn’t worry as much as Shaw about spoilers, but he ultimately agrees that warnings are a good thing — even if spoilers may not affect most fans.

“I think it’s useful to have spoiler warnings, but I think people are a little…. They take it a little too seriously.”