Does This Genetic Replica of Van Gogh's Ear Still Belong to the Artist?

Artist Diemut Strebe grew the legendary painter's ear from his and (his great great great nephew's) DNA. Who does the thing belong to?

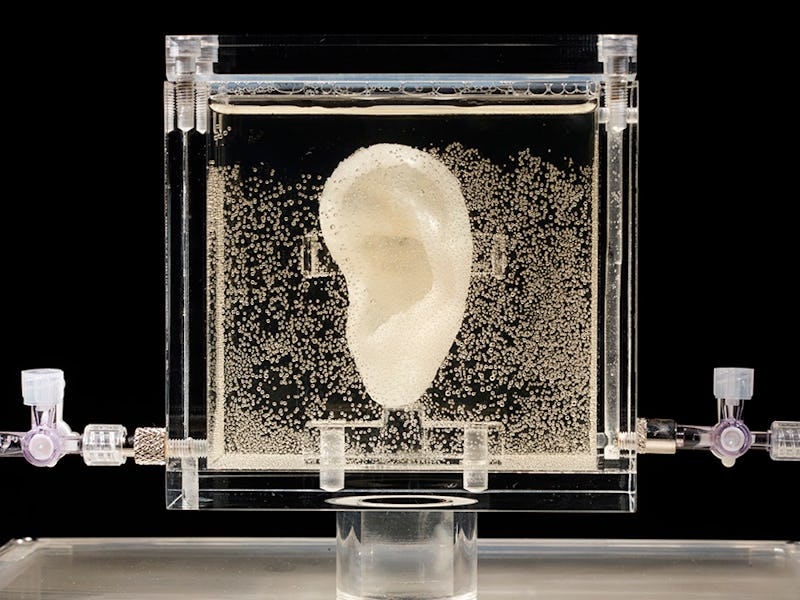

Vincent van Gogh, legendary cartilage-discarder, lives on today through his art and, now, through a genetic replica of his ear created from his DNA. It’s the creation of artist Diemut Strebe, who named it “Sugababe” and invites viewers to whisper sweet nothings into it. Noam Chomsky was the first to do so and thousands of guests from Karlsruhe to New York have followed suit. Strebe hopes guests will walk away from these one-sided conversations with this question in mind: Who the hell did I just talk to?

The ear is made from mitochondrial DNA extracted from a stamp Van Gogh allegedly licked in 1883 and cartilage cells from Lieuwe van Gogh, the great-great-grandson of the artist’s brother Theo. The final product is a multi-generational cellular and genomic collage, yet guests seem to dismiss the junior Van Gogh’s contribution as mere scaffolding for what really matters: the artist’s DNA. Linking DNA with the idea of a single human identity makes sense for now, says Strebe, but as genetic engineering makes it possible to cobble together a genome from multiple DNA sources, the link will only become more tenuous.

Conceptually, Strebe’s work is a CRISPR-age reframing of Theseus’ paradox, a 1st-century mindfuck posed by the Greek thinker Plutarch: If you replace all of a ship’s planks, piece by piece, over time, is it still the same ship? Is Van Gogh the artist really just cartilage and DNA just waiting to be Frankensteined into re-existence, or did his identity die with his body in the Auberge Ravoux?

van Gogh, Self-Portrait with Bandaged Ear

“It’s the principle of the scientific procedure that I was interested in,” she told Inverse, admitting that the stamp DNA was “probably the postman’s.” For Strebe, who the DNA actually belongs to doesn’t really matter. What matters is who we think it belongs to — that is, if it belongs to anyone.

Luckily for Strebe, the younger Van Gogh had made the mental leap necessary for her project to work. He wasn’t offended by the fact that she only sought him out because he carries one-sixteenth of his famous relative’s DNA because he didn’t think her project violated anyone’s identity. “I don’t really think I should have a special right over his DNA,” he told Inverse. In his eyes, DNA is an integral part — but not the defining characteristic of — personhood.

Lieuwe van Gogh, Self Portrait

Not everyone has such an easy time divorcing identity from genomic data. Other members of his family, he admitted, had “more conservative” views and were unwilling to support the project. Strebe’s encounters with Van Goghs who found her work too intrusive and “creepy” just served to strengthen her resolve to ask the questions they were unwilling to consider. “People have to realize where we are headed and which things we are navigating around,” she says.

In Strebe’s world, gene editing is already a given and bioengineering is standard practice. Avoiding the hard questions is simply procrastination. She’s here to save us time. “What’s been acceptable over the course of time changes,” she says. “We have to move the reference frame forward.”