MIT's Not Going to Open This 1957 Time Capsule Until 2957

"MIT likes to be rational and future-oriented, but this is a remarkably sentimental activity and sweet moment.”

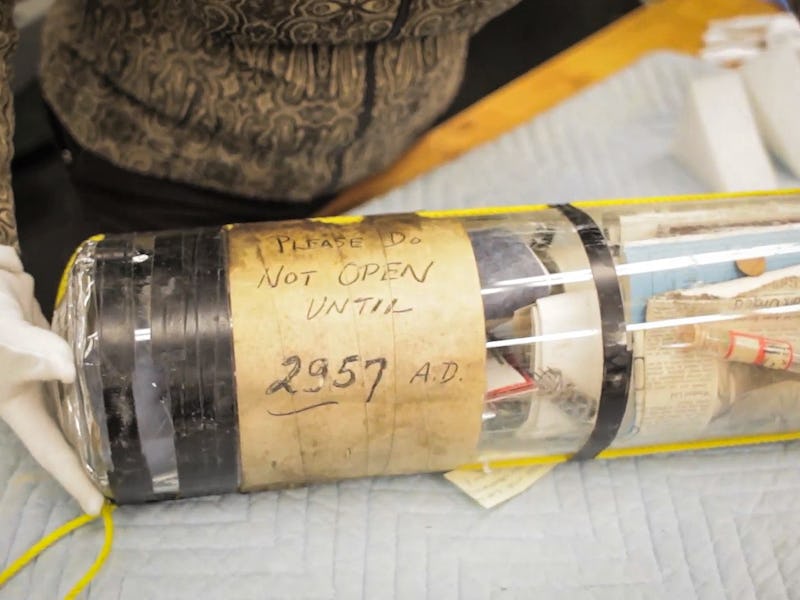

A construction crew at MIT was digging a foundation for a new building when they stumbled upon something old — a time capsule that had been buried in 1957.

There are strict instructions on the capsule that it is not to be opened until 2957. We have decided to follow the wishes of the original makers and not open it,” Deborah Douglas, director of collections for the MIT Museum, tells Inverse in an email.

But because the artifacts are encased in clear glass and because records still exist of the capsule when it was originally built, museum staff have been able to piece together parts of its story. They even found old footage of MIT professors stuffing documents and other things into the glass cylinder.

The capsule was carefully engineered so that the documents and artifacts inside would be preserved for a thousand years. The glass was specially forged at an MIT glass blowing lab, and it was filled with argon gas to preserve the contents, according to a news release from 1957. The designers even had the foresight to include a sample of carbon-14, so that if the glass was breached and the documents destroyed, scientists of the future could date the contents with reasonable accuracy.

Among the items inside were a vial of synthetic penicillin and a cryotron, a “revolutionary new electronics component,” according to the 1957 release. Both were considered remarkable examples of technological achievements by MIT in that year.

“MIT likes to be rational and future-oriented, but this is a remarkably sentimental activity and a sweet moment,” says Douglas in a news release.

There are at least eight known time capsules buried on the MIT campus. “It’s part ship in a bottle, part letter to the future, and we do it often,” Douglas says. “We seem to have this impulse to collect and to be deliberate about communicating with our future selves.”

What makes this one unique is how forward looking it is — a 1,000 years is an awfully long time for a glass vessel and its contents to survive undisturbed.

What did the MIT community imagine that 2957 would look like, back in 1957?

MIT President James R. Killian Jr. gives us a clue in a letter he wrote, to be sealed within the capsule. “To those who have come after us, greetings!” it begins. And later, “We cannot guess what the next millenium holds for the world or whether you will regard our age as one of science. But we are confident that you will have a greater understanding of the Universe and that we will have made some contribution to that understanding. We wish you continued success in the pursuit of knowledge.”

A 1957 photograph shows President James R. Killian Jr. (left) and professor of electrical engineering Harold “Doc” Edgerton burying the time capsule.

What’s next for the capsule? In the short term, it will be displayed at an open house next April to celebrate the 100th anniversary of MIT’s move from Boston to Cambridge, Douglas tells Inverse.

“The long term goal is to preserve the capsule but there are many ways to achieve that objective. There is much discussion about reburying it once the MIT Nano building project is complete.”