We Talked to the Co-Founder of the New National Video Game Museum

From preserving history to fostering the next generation, Sean Kelly aims to archive an industry built on moving forward.

Thirty miles north of Dallas, Texas inside the Frisco Discovery Center is where the National Videogame Museum will call home. When it opens this winter, the NVM will be the first museum dedicated to the history and science of video games in the U.S. There will be installations ranging from Pong projected on 15-foot screens, to artifacts and unreleased consoles, to a 1980s-style arcade with working Asteroids, Donkey Kong, and Space Invaders cabinets.

Despite the industry’s leaps in consumer tech and its leading role as a trendsetter the last 50-plus years, its stubborn fixture towards the future makes preserving the past remarkably hard. The museum serves to remind the industry and its hobbyists a few important things: To take stock, and to slow down.

Flappy Bird, for instance. The dumb smartphone game made up to $50,000 per day in revenue last year, but after a few weeks on the market creator Dong Nguyen removed it from app stores. Now, it’s gone. In the near future, if someone wanted to play Flappy Bird to see what moment millions of people shared, they can’t.

“That’s part of the problem,” Sean Kelly, co-founder of NVM says to me in a phone interview. “There was never an opportunity for an organization like us to preserve Flappy Bird. When that game was first pulled off the Apple Store, people were selling phones that still had it for $600, $700. That’s a big part of the problem.”

Of course it’s not just mobile games the NVM are preserving, it’s all of gaming. “What we’re trying to do is preserve history,” he says. “As you look back at all the people that started this thing, [they’re] starting to get up in age. Their stories need to be told and preserved.”

Sean Kelly has devoted his life to archiving gaming. “It was difficult back in the day to get people to take video games seriously, even today,” Kelly tells Inverse about his work, which has culminated with NVM. But why go through the trouble? He answers plainly from his office, “I’m sure I don’t have to tell you how big the video game industry is but it’s bigger than movie and music combined.”

He’s right. Just this year, Jurassic World grossed over $200 million opening weekend. Call of Duty: Black Ops III beat up that little twerp when it raked in $500 million its first three days. But will we remember? Every software update and HD re release is a step further away from a recognizable past. What will happen if gamers fail to remember their heritage?

Sean Kelly hopes that never happens.

The National Videogames Museum is the first video game museum, but there are other video game installations and halls in existence. What makes the National Videogame Museum different?

There is no dedicated museum specifically to video games anywhere else in the country. The closest one is in Berlin. We’ve been [building] it for the past 20 or 30 years, but what we’re trying to do is preserve the history of the industry. Whether you agree with the contents or not, Grand Theft Auto V made $1 billion in three days.

The other part of the museum that I don’t want to lose sight of is that video games are fun. My partner [and NVM co-founder] Joe [Santulli] is the biggest advocate of this. We don’t want to make a stuffy, “Look at fossils and never touch anything.” Video games aren’t meant to be seen that way, so the biggest part of our museum is that it’s hands on.

The idea is that you come into the museum, you buy a ticket, you wander around the exhibits, and you can hang out and play some games. You can go to the arcade and play some games, you can sit at this counter and play some games.

We want to set up some of the more obscure systems that people may never have heard of before. But it’s all about interactivity.

For a weekend in July, the National Videogame Museum opened its doors early to VIPs during the ScrewAttack Gaming Convention in Frisco, TX.

How did the museum begin to form?

The first thing [co-founders] John Hardie, Joe Santulli, and I started to do was track down these people who started to build the video game industry. We have a database of thousands of people. We’ve gone so far as to just pick up phone books — you don’t have to do that anymore but 25 years ago you did. We would pick up random phone books in cities and hotels and steal them and take them back home and John would literally just start cold calling people out of the blue, just in order to find these people.

Back in the day, the programmers weren’t credited with the games. That’s one of the reasons Activision was formed. People wanted credit. All of these guys were kept secret by the company, so it was difficult to find those people. The history of how the industry came together needed to be preserved. That was the launching pad for all of our efforts over the years.

How was Frisco chosen to become the home for a video game museum?

Ideally, you’d think that since the video game industry was born in Silicon Valley, you’d think that’s where a video game museum belonged, but we had a hard time getting municipalities in Silicon Valley to take us seriously. Frisco saw it right away. They had to have it.

We’ve been traveling and doing shows across the country — we do GDC, we do PAX, we do SXSW — for 10 or 15 years, and one of the biggest supporters that we’ve met was Randy Pitchford, president of Gearbox Software. We met Randy at one of the nice shows in Las Vegas that we were doing an exhibit at. He came in and loved what we were doing and he said, “We want you guys to come down to Texas.” The headquarters for Gearbox was in Plano at the time. He said, “Come down and check out the city I’m moving my company’s headquarters to,” which was Fisco. And we did! We came down to Fisco, met with Randy, and he took us around the area and introduced us to some of the people in the city council and the mayor and, like I said, they immediately saw the value to it. It just kind of snowballed from there.

What installations are you most excited about?

One of my favorites is the Pixel Dreams. It’s the 1980s arcade and it’s almost done. People who didn’t live through the ‘80s don’t really understand the significance of the arcade, but everything came out of the arcade. The desire to build more impressive video games than the arcade is what drove the industry. Now, home video games have taken over and arcades are a thing of the past. But the ‘80s arcade, and I guess in some sense it was still true in the ‘90s, the arcade defined the industry. It’s what the home video games industry aspired to be. It plays a really big part in the history of the industry, and that’s one of my favorite things.

The Giant Pong is a lot of fun too. We built the world’s largest home Pong console, and it plays on a 15-foot replica TV from the ‘70s. It’s a lot of fun. We also have a 40 ft. sq. section dedicated to the crash of the industry in 1983.

One of the staples of the National Videogame Museum is "Pixel Dreams," a recreated '80s-style arcade with fully-functional arcade cabinets.

With Atari and E.T.?

Yeah, and the other side of that area deals with the rise of computers. The video game market crashed in 1983 and the computer game industry kept going, forging ahead, and then Nintendo came out in 1985 and was a big hit. But there was a period of a couple years when virtually no video games were being made, except for computer games. So that area [of the museum] accounts for the different causes of the crash, the effects of the crash, and how things panned out in the end.

The crash exhibit also has a bunch of computers set up. We want someone to actually sit down and play [by typing] “Load asterisk, comma a, comma one,” and understand what it was like to play a game. That’s how games were loaded on Commodore 64, you had to put in a disk and type the command prompt.

Everything we’re doing is intended to be interactive. Even the rarest stuff that we have. If at all possible, we’re going to let people at it.

So the NVM is going to feature more than 100,000 consoles and artifacts. Was it difficult to curate all of these? What was the hardest one to find? Do you happen to have the Nintendo PlayStation?

One of the more interesting things we have is the Sega Neptune. It’s the only one in the world. It’s a Sega Genesis with a 32x built into it, and Sega never released it.

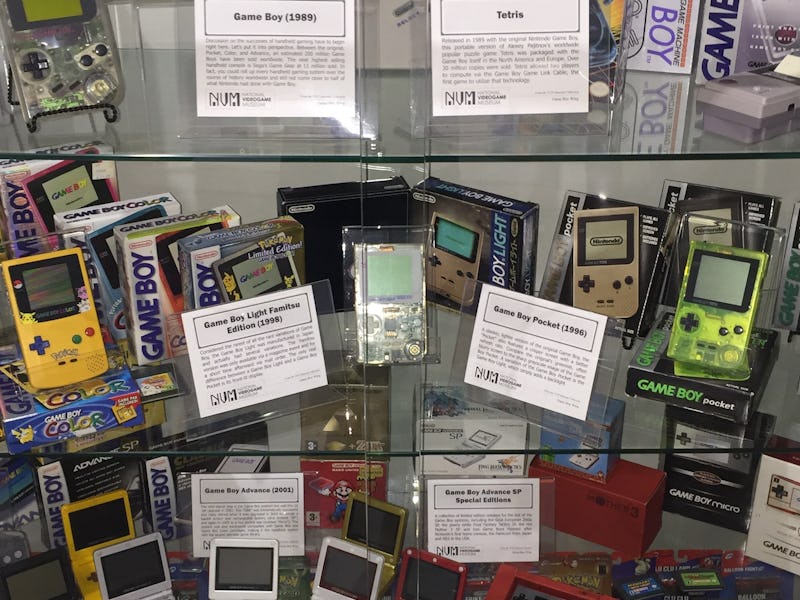

A sample of the collection inside the National Videogame Museum.

We have an RDI Halcyon which is a laserdisc-based game console. Very few made it out the door. It was very expensive. It was designed by the team who made the Dragon’s Lair arcade game. It didn’t favor very well because it was multiple thousands of dollars in the late 1980s, so very few people bought them. It’s rumored that there are less than 12 in the world. We have probably the most completed example of one. It’s still in its shipping containers and it’s never been used.

We have Atari prototypes, we have “His” and “Hers” Atari Lynx systems that were never released, and we have complete collections of software for pretty much every game console ever.

Wait, I’m sorry, I have to ask. Atari made “His and Her” consoles? Like, consoles gendered like lingerie?

By the time Lynx was out, Atari was getting desperate, so one of the displays we do a lot is we put two different or unusual Lynx we have out there. One of them is a pink Lynx that was intended to be called the “Her Lynx,” Lynx geared specifically to women and another one was a light blue that was geared towards men. There’s a third one that we have, which is a Marlboro Lynx. They were so desperate, they were branding video game consoles with cigarette companies and it didn’t really fly. [laughs]

I’m not surprised!

Atari at that time had been through the crash and had come out with not a very good reputation with consumers or retailers, so they were doing anything and everything they could to get their hardware into people’s hands. Some of that reeked desperation in my eyes.

So you’ll really allow people to play more some of the rare consoles and prototypes?

Within reason, of course. We have this thing called the Mind Link Controller. It was made by Atari and never came out. There’s only two of them in the world. Ours is pretty much ready for retail, but the mind link controller is strapped to your forehead and supposedly allows gamers to play games with their thoughts.

That’s huge!

Of course it doesn’t work. There’s no way in the world that was ever going to work. But what Atari did accomplish is if you make weird faces or grimaces or wrinkle your forehead in just the right way, you can get the reaction on the screen. It’s not your thoughts, it’s the skin that does that. As much as we would love to let people wrap this thing around their forehead and take pictures of their faces as they’re doing it, we just can’t let people play with it. It’s fragile.

A perfect example like that Sony PlayStation thing, maybe people don’t have to touch that but maybe we can wire controllers out so people can play a game on it. We certainly don’t want people popping disk cartridges in and out, but wherever possible, we’re going to be as creative as we can to allow people to use some of the rarer stuff.

One thing that really fascinated me about the museum is you’re trying to foster education in video games. The NVM wants to inspire kids to explore STEM careers. Could you elaborate on how you’ll accomplish that?

That’s actually really important to us. Again, it goes with the stigma that video games are just toys or a waste of time or whatever people that don’t understand them might say. The big part of it is that it’s not just about playing, it’s about understanding where games come from and understanding how to make video games.

There are thousands of different jobs in the industry, from art to sound to programming, and all of those are good jobs. They’re high paying, highly desirable. A lot of times, at all the different shows that we do, people ask, “How do I get into it?” That’s one of the big things we want people to understand at the museum. We want to give them an understanding of how video games are made and we want to give them a path towards a career in the industry.

You don’t know how many parents come up to us or even the kids themselves, saying “Johnny or Susie are really into video games and they want to know how to get into it.” So we’ve forged a strong relationship with SMU (Southern Methodist University), which is close by. SMU offers the only video game master’s degree in the country. Every student that goes through that school to get a master’s degree in game programming has to take a course on the history of the industry. Being in close proximity to our museum, one of the things they intend to do is bring groups of students into our museum to give them background and understanding about where games come from. Through that relationship, we’re also going to help develop a curriculum and develop classes, workshops, summer camps, all geared towards helping kids understand that there’s a lot more to video game than just playing.

A sample of the collection inside the National Videogame Museum.

What kind of other events might the museum host? Will there be panels, discussions, or particular classes people can sign up for?

We certainly do intend to host talks and private events. We’re very close friends with Nolan Bushnell who founded Atari and Al Alcorn who developed Pong. In addition to exhibits at different shows, we’ve also had our own show in Las Vegas for the past 15 years called Classic Event Expo and at that we’ve had literally thousands of people come and give talks and describe their involvement in the evolution of the video game industry. Steve Brosnick, Jody Pear, there have been literally thousands of them. We have relations with a lot of those people.

One of those things those people have been reluctant to do is hand over what they’ve accumulated without there being a place for people to come and see it. With there being a permanent exhibit, there’s a lot of things that we haven’t been able to secure in that past that will start making their way into the museum, including the people themselves! We’ll be reaching out to those people to give talks and describe what it was like to create the industry, their views of the current industry or what it’s lacking or excelling in.

A sample of the collection inside the National Videogame Museum.

A video game museum in 2015 crosses with where the industry is going now, which is almost entirely digital and physical-less. In the far future, how does the National Videogame Museum hope to preserve the new games today that will be relics tomorrow?

If a company is too small or too this or that to preserve their data, somewhere… take Angry Birds for example. It’s huge! But what if I wanted to play the very first version of Angry Birds? What if someone wanted to research and see what started it all? Why did people get hooked on this game? Does anybody have the very first version, does the company that wrote the game still have that first version? What if it’s gone?

As simple and dumb as Flappy Bird was, there was a big stink about that game for a while and that will never be seen again. The guy who wrote the game hates it and it ruined his life, but so what? For the better of the education of the people, there needs to be a way for that stuff to be active. People are doing little bits and pieces of archiving here and there, but we want to be the central archive for that. So when a game goes out on the Apple store every day, we want to be in with Apple, with the programmers, so we get an archived version of that game and it’s stored for posterity forever. I think that would be important.

The National Videogame Museum will open its doors in Frisco, Texas this winter.