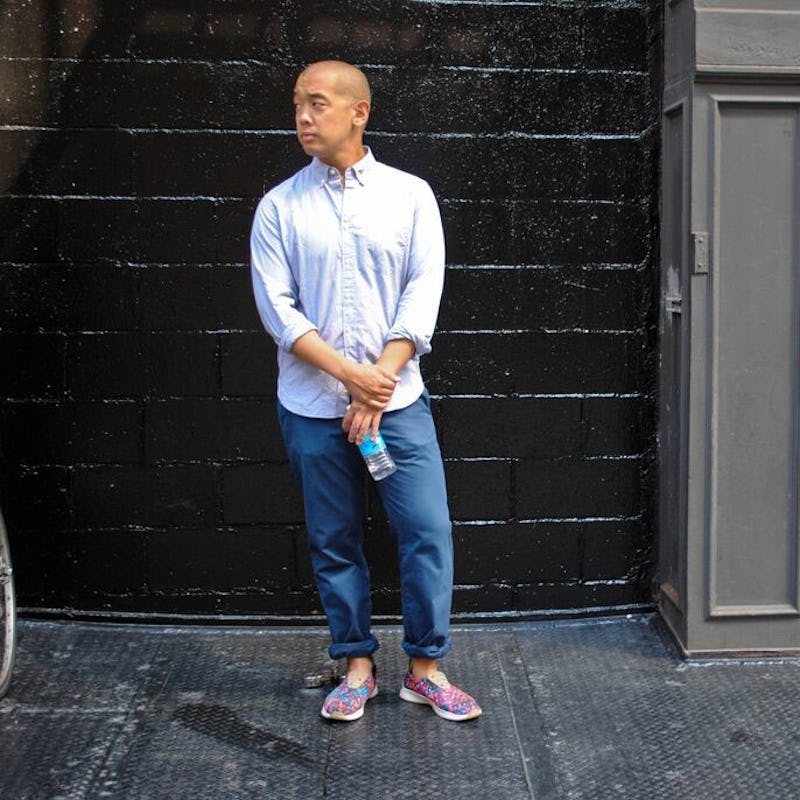

Jeff Ng, a.k.a. jeffstaple, Founder of Staple Design | JOB HACKS

Jeff talks building brands, staying on top of what's current, getting mugged in '80s new york, and pigeons

Careers rarely go according to plan. In Job Hacks, we shake down experts for the insights they cultivated on the way to the tops of their field.

Name: Jeff Ng, a.k.a. jeffstaple

Original Hometown: Freehold, New Jersey

Job: Founder of Staple Design, a creative consulting firm and lifestyle menswear collection that has worked with such brands as Nike, Microsoft, Sony, Lotus, Timberland, and New Balance. Staple was behind the coveted Nike Dunk Pro SB, which played a key role in launching sneaker culture into the mainstream.

How did you get your start?

I went to NYU for journalism, then I went to Parsons School of Design. I’m actually a double drop-out. Two colleges, four years of school, and no diploma to show for it — that makes my Chinese parents very proud. I started a company out of art school without really having the intention of starting a company. I was using the platform of a T-shirt to express my art: Where other people paint or illustrate or paint on a canvas, I was doing it on a T-shirt. That’s how it began.

Where did the idea to use a T-shirt for your canvas come from? Have you always been into fashion?

To be honest, I was intrigued by brands more than fashion. I remember when I was really young, I was infatuated with Disney — and not from an “oh, Mickey Mouse is so cute” standpoint. My parents would take me to Disney World and I would keep the napkin that had the Mickey head embossed on it, or the bar of soap that has the Epcot stamp. I couldn’t even articulate it as a kid, but I was amazed that someone could create a symbol and that symbol could appear on everything from soda cups to a bar of soap to a dollar bill in Disney dollars.

By virtue of being into brands, you end up being into fashion because you care about the brand you’re wearing. But I wasn’t avant-garde fashionable in school; I had no intention of starting a fashion brand. The reason I chose to put it on T-shirts was simply because I took the train, bus, and subway all the time. I realized that every morning, no matter what gender, color, race, religion we are, we get up and we make a decision about what we’re going to put on our bodies. Even if someone’s like, “I want to put on a dandy tuxedo with a top hat and a cane and tails” and another guy puts on a white T-shirt, busted Levis, and Converse Chucks — one guy says “I don’t care,” one guy says “I care a lot,” but they both made the decision that that was going to be an expression of themselves.

That is an incredible platform to then be able to build ideas on top of. That’s much more powerful than painting on a canvas and hanging it in your studio apartment that you and your eight friends will see. I thought, “This will be a canvas on my chest and I’ll walk around and this becomes a billboard for ideas.”

So how did you settle on the pigeon as your brand?

Probably on those commutes as well. I was born in New Jersey, which is more rural, and commuting in New York, I noticed there’s this animal that lives among us. Rats live among us too, but they don’t show themselves as much. Pigeons are very much like a New Yorker. They hang with us; walk next to us on sidewalks. Did you ever see those pigeons with one leg or a battle scar? They’re dirty and grimy. I feel like New Yorkers are like that. You take a beating and just have to survive somehow. Pigeons end up surviving.

Then I got into the culture of raising and taking care of them and I realized there’s a beautiful side to them as well as a historic side, like carrier pigeons in the war. I said, “Man, this is a really amazing animal, and it gets no love.” So I made it our icon. Now I see it on Instagram all the time. People will take pictures of pigeons and tag me in them, or they’ll say on Twitter, “I can’t look at a pigeon now without thinking about your brand.” That’s one of my proudest accomplishments: that when you look at a piece of vermin, you think of me.

And how did your fascination with New York come into play?

My parents worked in Chinatown, and I would come in with them and hang out at their warehouse. Whether this is good parenting or not, I don’t know, but as they would say, “Go out and run around and be back by 5:00.” So I was just on my own as a 12-year-old. I would start down in TRiBeCa and I would explore all the way up to 14th Street, Union Square, and make my way back down. That was my day. Just a 13-year-old kid running around, absorbing New York City.

I really got into the Village. Hip-hop was born in the mid-‘70s in Harlem, but by the ‘80s it came down to the Village. It was the rawest, coolest form of hip-hop you could imagine. I’m talking, people air-brushing on the back of denim jackets; selling mixtapes out the back of a trunk; DJ’ing from the corner. Then you had Astor Place, where they had the most famous old-school barber shop with barbers talking shit with each other. It was just so New York. Now you watch films that recreate that feeling, but I was really absorbing the realness of it. I was getting conned and pick-pocketed; I got mugged.

How old were you when you were mugged?

Fifteen. He stabbed me and he missed. Went through my jacket. I was scared shitless, but in retrospect, that was the fertilizer for me. It formed everything about my musical taste, my design sensibility, and I think that pigeon mentality formed with that too.

So since your background is in the arts, when you first started Staple Design, was it hard to grasp the business side?

I’m a self-founder. I have partners now, but for the first 15 years I had no partners. I didn’t go to business school, I’m horrible at math. I’m a creative mindset person. It was so much trial and error and making mistakes, but I wouldn’t have it any other way. It’s one of the best ways you can learn. That’s what makes you a good businessman.

Were there any mistakes you made initially that stand out?

When you start out, you can’t really go to a headhunter to hire people, so you end up hiring your friends. I used to play basketball in the city, and after we all finished playing on a Saturday afternoon, all the homies would be like “What’s everyone doing now?” Everyone would be like “I’m getting a drink” or “Meeting a girl.” I would say “I’m going to work.” I had orders to pack or I’d have to design a T-shirt. To these guys who have 9-to-5s and sit in a cubicle all day, they’re like, “That’s so cool you can go home and design a T-shirt and ship an order to Germany.” A handful would come over and pack orders or do whatever needed to be done. Eventually those guys became my employees, but I quickly learned it’s hard to go from being a friend to someone to being like, “You got that order wrong.” It’s difficult to say, “You did this wrong, go do it right.”

It becomes weird. You can start a business and become friends with that person, but it’s got to be rooted on a professional level. If you go from friend to business, I’ve never seen it work. When you run your own company, it’s a 24/7 operation. The clock never turns off. That’s a lot to ask of your friends or loved ones. It ripped up a lot of relationships.

Since fashion is such a mercurial industry, how do you keep your fingers on the pulse of what’s current?

I’ve learned to trust my instinct. If you start doing camouflage as a theme or trend — you notice it happening, so you start to inject it into your designs — you’re seeing something that’s trending and then you incorporate it. But if we just trust our instincts like, “I’m feeling camo right now. I don’t know why, but my brain is just telling me to do camo,” then people start looking at you and saying, “Because he did camo, that’s going to be a thing now.” That’s where it becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy. I listen to myself and I don’t second-guess my gut.

But I find that some of the things we hit are too early. We make the mistake of being on something and it doesn’t sell well for us, and then in two years it becomes a hot thing. We’re like, “Man we were doing that two years ago and now it’s blowing up.” We’re already on the next thing, which is not selling so well for us and then two years on, it will. In fashion they have a term called “the speed of fashion.” Merchandisers and buyers will look at a design and say “It’s too fast.” It means you’re ahead, you need to slow it down; water it down, so now you’re six or nine months ahead — not two years ahead. We’re training ourselves to do that.

The idea of branding has really evolved today from what it was even 10 years ago, and the general public is much more aware of it as a concept. Has that made business easier or harder?

I ask myself that question often. I tend to think it would be a lot easier to start a brand today than 20 years ago, because of the tools at your disposal. The flip side of that coin is the competition. Everything is easier to do; if I were to start my T-shirt company today, I could make a T-shirt on my phone now. They have apps that you can make a T-shirt on and order one. Before, I had to find the silkscreener, make an order, then to promote it, I had to get a stack of fliers printed, walk around and hand them out at cafes. Now I can make the shirt online, take a screenshot on my phone, Instagram it, and then I can see in 30 minutes that 400 people liked it and 23 people want to buy it.

So the ease is much better, but the problem is a thousand other people can also do that same thing now. But I tend to think if you start a creative business, the cream rises to the top in any decade you do it. So whether you’re a caveman doing it or whether you’re George Jetson in the future, if you are good, you will be good no matter what. Good designers can make beauty out of trash, whereas I think there’s a lot of people that — with the use of this technology — can smoke-and-mirror a brand. But there’s very little longevity in that. You see an artist or designer that’s hot for one year, maybe two, and you don’t hear about them anymore. It happens all the time. Not a lot of people can pass the five-year mark.

What advice would you give to someone looking to create their own brand?

Patience is key. Back in the day, you could build a brand or business organically, and marinate it like fine wine and take your time and build a fanbase and grow it. Today, everyone’s got their pants down: Everyone can see everyone else because of statistics, analytics, follow count, likes, comments. So if you’re a singer, and you just want to put out your video on YouTube, if you’re a 15-year-old kid and you see all these other kids have 1,500 views and you have 300 views, you can’t help but feel bad about that. That sucks.

I feel like that pressure forces that kid to do things he wouldn’t normally do if he was just operating in a basement, honing his craft while no one was watching. Now, because he wants to get a million views, he would do whatever it takes to get a million views. That means, if it’ll get more hits for a girl to do her song wearing a bikini, she will. I know a photographer who said, “I get more business when I put selfies up.” Maybe if there was no Instagram, she might have been the next Ansel Adams if she was just in an apartment shooting; but now she might be the next Jenner sister. It really pressures people and puts them in an awkward position where it’s not about honing their skill, it’s about promoting themselves better. So if you can somehow beat all of that and really just hone your craft, that would be my biggest advice to the young entrepreneur.