The Unexpected Physiology of Jump Scares

Science says that this article will make you easier to startle.

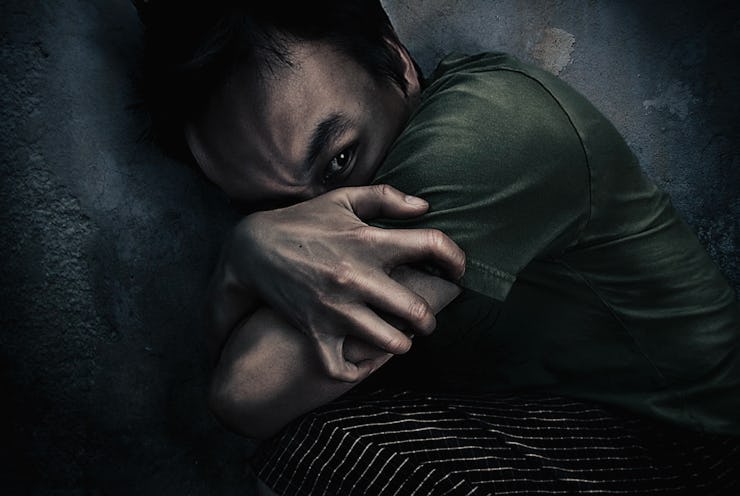

The jump scare doesn’t seem like it should work. Horror movie watchers know that someone is going to jump out — that’s why they watch horror movies. But still, neural circuitry is undeniable and the pleasure and pain of the involuntary flinch is all but unavoidable. The startle reflex is an evolutionary holdover that we share with virtually all mammals, including lab mice. What makes a jump scare work, at its core, is pretty simple: Set up a tense, lingering scene, and then break that in half with a sudden burst of sound or motion. Anything that ever evolved to avoid being eaten will flinch.

“The best way to evoke a startle response is with a sound, but touch or flashes of light work, too,” Christian Grillon, PhD, a psychophysiologist who studies fear and anxiety at the National Institute of Mental Health, tells Inverse. The impact of a startling stimulus depends on two physical characteristics: its intensity as well as its so-called rise time, or how sudden and powerful the stimulus is. “A shotgun or a door slamming will make you startle,” Grillon explains, “but a plane that takes off will not because the intensity of the noise only increases gradually.”

Take the ur-jump scene, a masterful bit of spooky cinema in the original Alien flick. It’s all quiet on the galactic front, until, abruptly, it isn’t:

The fact that you knew that was coming did nothing to stop you from flinching. In fact, it may have done precisely the opposite.

Say the night is dark and full of terrors, or you’re about to settle in to watch some xenomorphs and you’re on edge. Paradoxically, that makes the jump, when it comes, worse.

When you’re hyperviligant, you activate your amygdala, the bit of your brain that deals with fear and anxiety. The amygdala also happens to be end of the direct neural connection involved in the startle pathway. “If a startle-eliciting stimulus comes, then the startle will be much larger than in a non-anxious state,” Grillon points out. “In my lab, when I make subjects anxious and then I startle them, the startle reflex can be increased by 100 to 300 percent.” Posttraumatic disorders, too, can also prime people for startling. “This is not because a slamming door remind them of their trauma, but because they are chronically anxious and the slamming door makes them startle.”

Our responses to the stimuli we’re primed for are not particularly complicated. “The startle response is a very simple reflex with a few synapses from sensory processing (e.g., from the ear) to the motor response,” Grillon says. “Because it has very few synapses, it is elicited very quickly.”

All told, the reaction takes about 20 milliseconds in humans. And late October’s ghoulish atmosphere sure ain’t helping.

“At Halloween, when you are anxious, uncertain, loud sounds, flashes of light, or a touch on your back will make you jump more than normally,” says Grillon.

And preparation does the opposite of prepare you. Knowledge, in this case isn’t power, so the next time you think something might jump out and you remember this article, well, it’s only going to make matters worse.