Exploring 'Alien': Why We Never Got The 'Alien vs. Predator' We Deserved

How a universally-adored comic turned into a universally-loathed movie.

Alien vs. Predator is a misfire of epic proportions. Of all the spin-offs surrounding the main body of Alien films, it’s one most often referred to as a missed opportunity — an adaptation that collapsed in the transition from page to screen.

The crossover originated in a special three-issue prequel comic under the Dark Horse Presents title. The arc spanned from 1989 to 1990 with the first iconic image of the two creatures reserved for the final cover, emblazoned with the title Alien vs. Predator. The success of this short run launched a whole new series, kickstarted that same year with a four-parter that echoed the success of its predecessor. A wave of one-off specials, novels, and special magazines expanded this new area of the shared universe.

What sets it apart from the far-fetched crossovers in the Alien saga is how it crafts a believable mythology. Batman and Superman punching xenomorphs stretches the suspension of disbelief to a breaking point. But a Predator, a hunter by its very nature, harnessing the alien as part of its traditions? It’s inventive. The Yautja race keep an alien queen imprisoned within a torturous device, allowing them access to her never-ending stream of eggs. Those translucent ovals are shipped to various planets where the Predators use their emergent beasts as part of a rite-of-passage for young hunters. To become accepted they must kill an alien. In the first official AvP comic — the four-parter — the Predators take colony planet Ryushi as their next battleground, and naturally, a ton of expendable humans are sacrificed for their ability to nurture xenomorph embryos.

Then came the inevitable film adaptation.

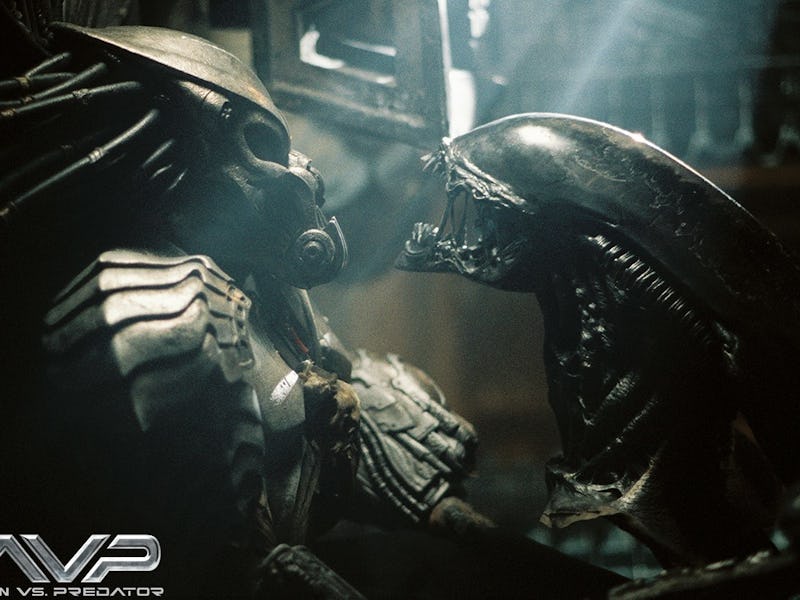

What’s wrong with Alien vs. Predator, exactly? What’s right with it might be the more pertinent question. The fan-bait showstopper of seeing Predator and Xenomorph in the same shot is pretty damn cool…

… However, a standalone moment in an otherwise terrible film doesn’t make the surrounding guff any more tolerable, no matter how long you’ve waited for it. Connecting two separate brands reliant on extensive prosthetics, special effects, post-production CGI, and introducing a human element, the movie buckles under the weight of its obligations. The former takes precedent over the latter, leaving an impressive spread of monsters laying waste to fodder characters devoid of personality.

Spectacle wows when it’s in the right place — in Aliens the sight of the monstrous queen takes nearly two hours to arrive — not served up on a platter at the expense of well-developed characters. Director Paul W.S. Anderson’s panache for kinetic action, as evidenced in every single of one his movies, trumps the nuances of the source material.

Where’s Machiko Naguchi, the warrior human who joins the Predator army? And why is Charles Weyland thrown under the bus with a hokey death that would have better served a snivelling douche like Burke?

More importantly, why does the alien queen suddenly possess the speed and agility of Usain Bolt?

What’s most interesting to note about the development of the film is the players involved. Dan O’Bannon and Ron Shusett worked on the story with Anderson. They’re the creators of the franchise, who co-wrote the original Alien screenplay. It’s difficult to believe that O’Bannon in particular, whose reputation as a stickler for details followed him throughout his career, would permit such egregious treatment of his creation. Did they fall asleep during early story meetings? Or were they happy to float along just for the cash? Neither, apparently. O’Bannon later revealed that his story input was ignored by Anderson. That idea would have furthered the mythology of the Alien life cycle, with the Xenomorph turning into a Predator as the last stage of its development.

The same frustrations that beset O’Bannon struck screenwriter Peter Briggs just as hard. Back in 1990 he tapped out a spec script for the movie which he successfully sold to Fox. News of the project sent Sigourney Weaver running for the hills, only promising to return for Alien 3 if Ripley were killed off to ensure she’d never appear in the crossover. It was either Weaver’s opinion or production on the third movie that put Briggs’ work on hold. The studio eventually passed on his script, picking up with a pitch from Anderson in 2002.

Of course, there’s no guarantee that Briggs’ script would have fared better — not all loyal adaptations turn into brilliant films — and it’s likely, as he said himself that Fox would have resisted his take due to the high cost of bringing his vision to the screen. “There’s a terrific Alien vs Predator movie still to be made by someone,” says Briggs. “It just hasn’t happened yet.”

I agree with him.