The Nine Lives of San Francisco's Presidio Pet Cemetery

What is the appeal of a 63-year-old pet cemetery in a historic urban park? Plenty, actually.

In Stephen King’s 1983 horror novel Pet Sematary, the main character buries his dead cat in a pet cemetery that doubles as a haunted Indian burial ground. A local had told him that the cemetery makes animals come back to life — albeit in a horrific, zombie-like fashion. To cover up the mistake of letting the cat get too near a busy road, he resuscitates the animal, only to find its behavior changed and its odor … intensified.

Meanwhile, in San Francisco, it’s the cemetery, not the pets, that has achieved near-immortality.

Established in 1952, lore holds, by Lieutenant Colonel Swing, and maintained, at varying times, by the Boy Scouts of America, Swords Into Plowshares, and volunteers of the Presidio Trust, the Presidio Pet Cemetery is located — naturally — in the Presidio, a park and former military base that is part of the larger Golden Gate National Park of San Francisco. Real estate does not get more prime.

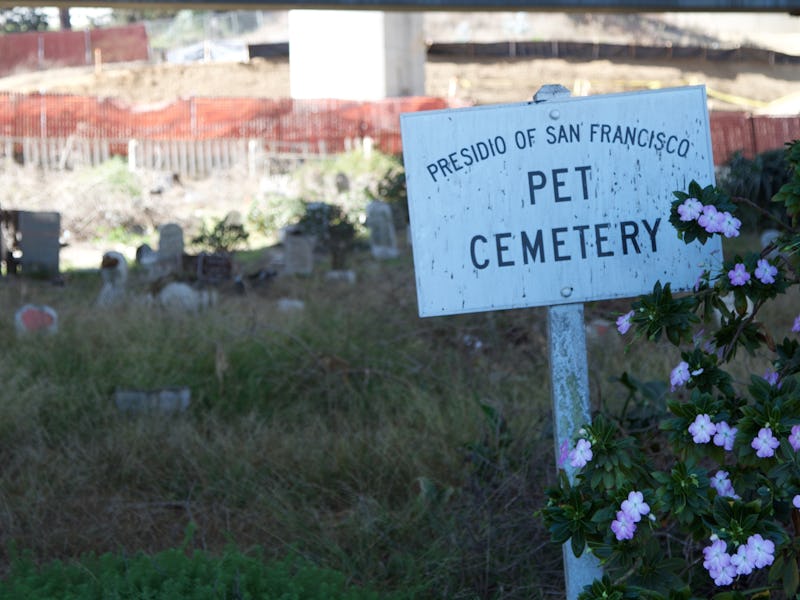

Despite being only a half-acre, the cemetery is an intriguing patch of land, and a source of near-endless conjecture. Simultaneously endearing and macabre, funny and sad, and delightfully fringe, it looks, appropriately, like something that has survived numerous attempts on its life — so many, in fact, that you might wonder, why go to such lengths to keep it around?

“The cemetery is a historic site within a national landmark,” says Dana Polk, spokeswoman for the Presidio Trust. “We maintain the Pet Cemetery as a cultural resource even though it is listed as a non-contributing feature in the Presidio of San Francisco Historic Landmark District.”

Is it heartless, calling the cemetery a “non-contributing feature” of the Presidio … or is it fair? What’s all the fuss about, anyway? Pet cemeteries ought to fall somewhere between actual human graveyards and parking lots in terms of sanctity. Right?

Not quite. Not in San Francisco, anyway. Routinely ranked one of the pet-friendliest cities in the country, the SF community has outdone itself, embracing the cemetery’s tender purpose and murky backstory as though it were a treasured pet.

Ltc. Swing broke ground on the cemetery so that “the tenants of the Presidio [would] have a place to bury their pets as was customary in other [military] posts.” These days, the cemetery is maintained in order to provide a sense of what life was like for military people and their families during those difficult, lonely times at the edge of America.

“It’s a window into another time,” says Molly Graham, a spokesperson for the Presidio Parkway project.

And there’s a lot to be seen through that window. Take a look at the 468-page document — assembled by a Presidio Trust volunteer — that meticulously photographs, charts, and records the conditions of each of the cemetery’s 424 graves.

Sonny the fish. Raspberry the Bassett. Mabeldog and Sally Sparkle. Kit Kat Binns. There’s something sweet and funny about the sanctification of these animals, an irreverence that almost cheats death. Dead animals: cuddly even in the beyond.

But is tranquility the name of Presidio Pet Cemetery? Also not quite. When the National Park Service took over the Presidio, one senator balked at the park’s then-$25 million dollar budget, even sending out pictures of the cemetery to constituents under the headline, “Is This Your Vision Of A National Park?”

And it’s hardly idyllic now. Birds chirp, the Bay Area’s bright sunlight bends and stretches, but for the most part, the cemetery looks and smells like … construction. Tall concrete pillars flank the half-acre of land like giant headstones. Unlike the endearing pet gravestones, their veneers are bereft of loving inscriptions.

The cemetery’s half-acre of land rests under Doyle Drive, an elevated stretch of Highway 101 that runs over the Presidio, departing San Francisco to the west over the Golden Gate Bridge, and to the east and south, winding through the city like an artery.

The Doyle Drive reconstruction is part of a larger $1.1 billion project called the Presidio Parkway, an effort to earthquake-proof that stretch of US 101 as well as improve conditions for walkers and bikers in the park.

“It was fairly simple, from an engineering standpoint, to put pile foundations in the ground to hold up the concrete beams that would support the falsework needed to construct the bridge,” she says, a move that, as a bonus, also protected the cemetery from debris — though that wasn’t its original purpose.

According to Graham, keeping the cemetery intact during this billion-dollar overhaul made sense.

The Parkway’s project planners didn’t separate the cost of the measures taken to preserve the cemetery from the overall environmental budget. But as she says, they weren’t really asked to. “That area of Doyle Drive was always going to be elevated,” she says. Furthermore, getting rid of the pet cemetery would have been costly in a different way.

“The San Francisco community is very attached to this parcel of land,” she says. Leaving aside the fact that the cemetery is an environmentally sensitive area, “it is also what I like to call an emotionally sensitive area.”

In fact, Graham says she’s had a number of inquiries about maintaining the cemetery within the Parkway project at large.

Everyone involved has their favorite pet backstory, and many bring a smile — though not all of them. Graham’s favorite gravestone is for Yellow Parakeet, “who lived six happy years.” Clay Harrell, another spokesperson for the Presidio Trust, mentions the gravestone of Margaret O’Brien, a native of county Donegal, Ireland.

“This is the only headstone that is apparently not for a pet,” he says. “There are various theories on who she was and how she got there,” among them, that she was a military laundress.

(Asked what her favorite Presidio Pet Cemetery story was, Dana Polk replies, with an evident wink, “I haven’t been able to dig up any.”)

Indeed, there’s an unavoidably dark and funny charm to this small plot of land, and something endearingly underdog (if you’ll pardon) about keeping alive the fuss to keep it intact. But that’s if you can ignore the orange netting, the pillars, and the noise, and the fact that, for the moment, the cemetery is a bit unkempt.

“The pet cemetery is typically maintained regularly by volunteers as part of our volunteer program,” says Holt. “However, it is currently inaccessible due to the highway construction. We will not have access to weed, etc., until the construction is complete.”

In the past, Swords to Plowshares, a non-profit in San Francisco that provides “wraparound care” for military veterans, contributed to the cemetery’s upkeep.

Asked to provide comment, Brian Jarvis, an associate with Swords to Plowshares, says, “Our history with the Presidio Pet Cemetery is limited to a group of informal volunteers who took it on themselves some years back to maintain the cemetery while living at our nearby Veterans Academy, until they either moved on or were no longer physically able to do so. To my knowledge they are no longer involved.”

Nevertheless, the cemetery is scheduled to receive a facelift as soon as construction is done. The help will have to come from volunteers, or the Trust itself.

Those stodgy pillars will go away — in fact, “they’ll be crushed on site, and recycled,” Graham says. Until then, visitors to the cemetery are held at bay by an orange construction fence. Only via a high-powered camera — or one of the cemetery’s many fansites — can one get too far in.

Kempt or un-, the cemetery functions as a tribute three times over. It’s a monument to military people and their service, a “window to the past,” as Graham put it. It’s also a testament to the pets who were of comfort to those military folks, and their families.

Finally, it’s ennobling to the rest of us, and to our pets. Part of it is the absurdity of some of the names — Poochie, Sheesa Nut, and (in true military fashion) Snafu. The pet lovers of SF get to believe that their animal’s warmth and unconditional love persists, even beneath a slab of asphalt around the corner from the Golden Gate Bridge. A gravestone near the fenced-off entrance says it best: