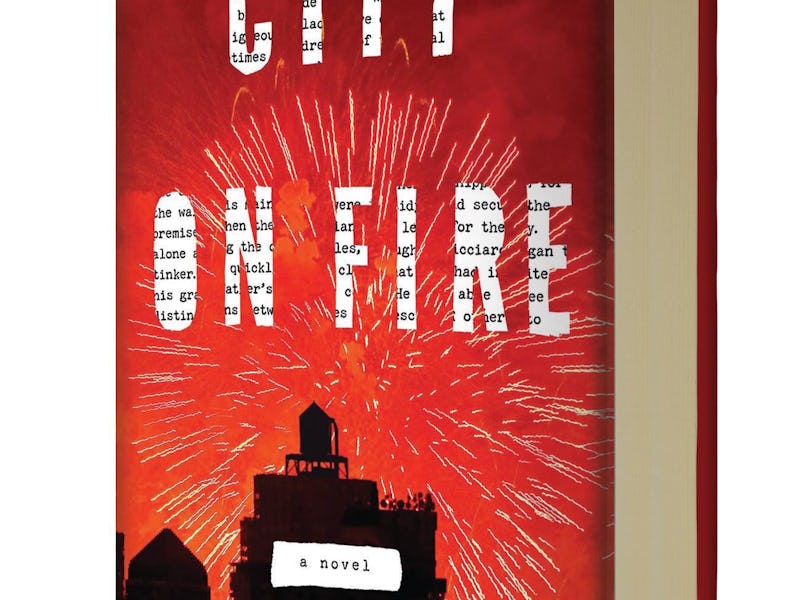

'City on Fire,' Fall's Most Hyped Book, Is Pretty, Pompous, and Overlong

Garth Risk Hallberg's debut built expectations to match its ponderous word count, at its peril.

Garth Risk Hallberg’s City on Fire cannot help but catch your eye on its hype alone. A first-time author with an unprecedented $2 million advance, an instant movie deal before it even came out, a page count that’s up there with Infinite Jest, publishers trumpeting it as a masterpiece, magazines breathlessly pondering What It Means — this is a circus as much as it is a book, at this point, destined to disappoint. If it’s not the second coming of Middlemarch, we can only hope it’s so offensively terrible it at least kicks up some decent schadenfreude.

After mowing through this tome, I can tell you, it’s neither great nor terrible, but resoundingly, depressingly middle-of-the-road. It has Infinite Jest’s verbosity without its innovative weirdness — it tries, a few times, for some avant-garde magazine inserts within the story, but it feels tacked-on and doesn’t blend. It has A Visit From the Goon Squad’s scope and subject matter — a cast of characters with overlapping lives in New York, spread out over many years and liberally sprinkled with ‘70s punk music — but it lacks Goon Squad’s vibrance and Jennifer Egan’s deft hand with characterization. It has a Tom Perrotta style sensibility of featuring lots of quietly unhappy couples who interact in fits and bursts until it culminates in a climax, but it lacks Perrotta’s hypodermic satirical wit. It evokes any number of other novels, but it’s more tediously bloated than any of them.

What it lacks not is an outsized ambition to be a Great American Novel. We know this because the words “Great American Novel” appear on page 5, filtered through the lens of a character (Mercer) who is trying to write one. You could argue that it doesn’t mean Hallberg is, but the presence of the phrase on the page shows that the phrase was floating in his mind. Putting the words into a character’s mind so early in the book is no slip, even if it could feign one.

The Great American Novel, like the American Dream, is an outdated concept that’s essentially meaningless, but whenever a book strives to reach this nebulous place instead of being the best book it can be, it falls short. Unfortunately, like Donna Tartt’s similarly tedious and far-too-long The Goldfinch, the page count unspools heedlessly — otherwise how will people know it’s Grand and Important?

City on Fire does inadvertently pose an interesting question, by its very existence: Is it possible to have a Great American Novel today? Unlike Hallberg, I’ll cut to the chase. The answer is a resounding nope, at least not in the antiquated way we used to think of it; not in the way City on Fire is trying to be. And that’s fine. More than anything else — any of the ideas City on Fire wants to present — it shows us we need to say good riddance to the concept of the Great American Novel.

City on Fire does not need to be 925 pages long. Hallberg is a very good writer, but his insistence comes at the cost of being a good storyteller. His sentences are gymnastic routines that vault right past his characters. In one passage, a character named Keith, who isn’t too bright, thinks, “why this munificence all of a sudden?” (page 276). People who are not smart do not use words like “munificence” in their private thoughts. Hallberg proves, though, that people too smart by half in fact may.

City on Fire could have been a good book if only someone had hacksawed 400 pages off its boughs. Gone would be the many unnecessary segments, the side diversions, the whatever sentences that offer only weird similes (“her palms were like cool carnivorous plants”). It could have evoked emotion if it has aimed to build a logical structure. One main character, Jenny, first wanders into the book at page 363, too late for us to care much about her. The subsequent detour into her life makes us care less about the other characters by the time we catch up with them. The novel claims to be about the New York City Blackout in the summer of 1977 — but can a book really be about something that doesn’t happen until page 785?

City on Fire is the literary version Crash, 2004’s Best Picture Oscar winner and the movie retrospectively coined The Worst Best Picture of All Time.

Critics railed against its racial stereotypes and failure to produce characters with functional inner lives, and yet it won the big award anyway. In City on Fire’s first 200 pages, the characters seem to be a diverse cast with developed inner lives. But it’s around 300 page mark — when we learn that the dumb guy thinks words like “munificence” — that that illusion unravels, revealing the characters as the author who keeps putting on a fake Groucho Marx mustache to fool you into thinking he’s several different people.

For a lesson in how to jump into wildly different consciousnesses — not to mention, how to have better developed characters in 300 pages than 900 pages — look to A Visit From the Goon Squad. Now that’s a great American novel, because it’s not trying so hard to be. That it began its life as short stories points to a solution: Take small bites, authors, and chew each one slowly.

I keep coming back to City on Fire’s length only because its flaws would be far more forgivable if this book were not 925 goddamn pages long. It’s a three-star book, and I often like three-star books; their flaws are usually the result of the author trying something that didn’t quite work. I respect a 300-page 3-star book, but one that asks you to invest this much time in it is another matter entirely. Ian McEwan controversially spoke out against long books, saying “very few earn their length,” and while he isn’t right on every account, his words apply here.

The Goldfinch and the bloated later entries to the Game of Thrones series underscore this mistaken impression that bigger is better. I get it; when you’re charging $30 for a hardback (in part to cover that $2 million advance) you need to convey to a book-buyer that they’re getting The Great American Novel, or at least a prestige-read. Instead, you’re pawning off a 925-page word blizzard with a reach far beyond its grasp. City on Fire, blandly inoffensive, ultimately leaves an impression of trying so hard to say something meaningful that, while it says a great deal of things — too many things — they don’t stick, but rather dissipate the instant you close it with a deep thud.