Conducting 'Back to the Future' Live: a Q&A with Composer David Newman

Coming soon: live orchestral accompaniments of screenings at Radio City Music Hall.

For two performances on October 15 and October 16, the New Jersey Symphony Orchestra will play a live accompaniment score to screenings of Back to the Future at New York’s Radio City Music Hall. In attendance will be original score composer Alan Silvestri, as well as screenwriter and producer Bob Gale, and star Christopher Lloyd. The whole thing is being put on by the appropriately named Film Concerts Live, who have run similar accompaniment performances for Raiders of the Lost Ark and Star Trek.

We can’t think of a more epic way to celebrate the 30th anniversary of the BttF trilogy, so we talked with David Newman, the man who will conduct the music at the famed venue along with the classic film. Newman has provided his own original music for more than 100 feature films, working with such luminaries as Tim Burton, Frank Oz, and Joss Whedon. This isn’t Newman’s first rodeo. It turns out, Newman might be the perfect man for the job.

Sean Hutchinson: You’ve had a long career of composing music for films, but I was curious, is this the first time you’ve conducted an orchestra live?

David Newman: No. I’ve done this sort of thing on and off my whole career.

I started working at Sundance in the late ‘80s, and I did silent films there and a bunch of concerts there, but not a lot of movies. But I did score a live movie there once. It was Murnau’s Sunrise.

I really ramped this up in 2011, when we started doing West Side Story. And it’s kind of ramped up year by year.

SH: Was that West Side Story to the movie playing in the background or was it just the music performed?

DN No, all this is like going to the movies. It’s hard to explain. People don’t really get it until they go, but it’s essentially like going to a movie theater, watching a movie, except there’s a live orchestra there and they’re playing live under the movie.

SH: How did you get involved in this particular project with the Back to the Future performances?

David Newman

DN: Well, first of all Alan Silvestri is one of my best friends from like Sundance days, from the ‘80s. And the company that does these performances, IMG, I’ve done a lot of stuff for them. So there’s certain producing entities that do this stuff.

It started off kind of not that much, it’s gotten more and more. I’ve done like seven or eight of these different movie performances. This is my third Back to the Future but I think it’s been done a ton of times already this year.

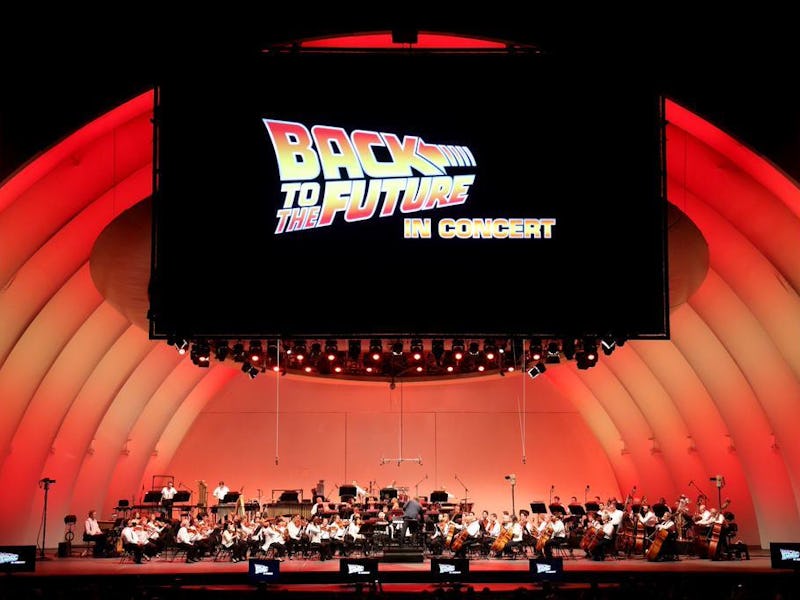

We premiered it in Lucerne I think in July or late May in Switzerland. And then a couple weeks later we did it at the Hollywood Bowl. I know it’s been done at the Wolf Trap Opera in San Francisco, and I’m sure many more places.

SH: Were you a fan of the Back to the Future movies before and the score in particular?

DN: It’s a perfect movie with a perfect score. I mean, I don’t want to be hyperbolic about it. It’s a perfect movie for what it is. And the score fits it perfectly.

My wife and I remember when we first saw it in 1985; we went opening night. We went to Westwood and then the next night we went and saw it again. It’s an amazing movie. I don’t know exactly what it is about it. Michael J. Fox is so great in it and Christopher Lloyd is so great, and they’re such a great pair. And then the last half of the movie they’re chasing a lightning bolt, essentially.

It’s just a breathless movie. And it’s essentially chasing a split-second thing, so this score is like this big clock and its tick-tock, tick-tock, “Oh my god are we going to make it? Are we going to get there?” And it has a wonderful, what we call in music, a coda, the part of act III when he gets home and sees what’s different. There’s no explanation as to why it’s different. You go back in time and do something and who knows what the hell will happen? And then it’s got the greatest ending of a movie almost ever —

SH: Sure. They just fly off in the DeLorean.

DN: Yeah! And Doc Brown says, “You’ve got to come with me! There’s something terribly wrong!” But they don’t explain what’s wrong. “Marty it’s your kids!” But what’s wrong? Who knows? And then it leads perfectly into the second one.

SH: How do you think Alan Silvestri’s score lends itself to this specific sort of live performance?

NM: Alan looks at it like a big band or a big drum set. A lot of film music is about rhythm. So if you listen to funk, like James Brown or R&B bands with big-brass sax parts and all that, they’re playing to melody, but the emphasis is on the rhythm. The score has a big rhythm section. It’s got a big wonderful, memorable theme. But most of the score is just rhythm stuff and motifs that fit together, particularly in the clocktower sequence at the end when the storm starts after Marty plays Johnny B Good and everything works out, and it cuts to Doc. That whole sequence. The music from there really follows him all the way to the end until he catches the lightning bolt at the right place and he’s able to go back to the future.

Even the title Back to the Future: what a great title. What the hell does that even mean? It’s a very interesting conundrum for your brain about what that title actually means, if you think about it. In the movie it makes sense, but ‘future’ and ‘back to the past’ and everything affects each other and it’s never really explained. There’s all this stuff left unsaid.

To me, it’s almost a perfect movie. The music, the energy, the art direction, the cinematography, the brightness of the color. There are not a lot of special effects in it, there really aren’t.

SH: Yeah. It seems like a big special effects movie but I think there are only about 30 special effect shots in the entire thing, maybe less.

DN: Yeah. it is not a special effects movie — it’s a character movie. And it’s a concept movie about about time. The opening sequence with all the clocks ticking … it’s great.

SH: As for the actual performance, can you explain the logistics of conducting and playing music live to accompany a film? I would imagine keeping up pace and staying in sync with the movie is extremely difficult.

Newman conducting an orchestra.

DN: Sure, it’s difficult, but it’s the same as scoring a movie. Except when you’re scoring a movie you do it in pieces and stop and screw up. But here you can’t stop when you screw up. But we use all the same techniques. We use this screener and punch system called the Newman System that was developed by my father Alfred Newman and 20th Century Fox sometime in the ‘40s. Maybe it was developed before then.

It’s a system with little lines that go from the left of the screen to the right side of the screen, the sync point. There are little flashes that you put in the score so you can tell whether you’re on or off. The little flutters are like navigational buoys. The easiest way to understand it is as you’re going along in rhythm bar and beat, it’s always a little off. You see a flutter and say, “Oh, I’m too slow.” Another flutter: “Oh, I’m too fast! I gotta slow down.” And then you see the lines going across. It’s like how an airplane is always adjusting course. But when they land, they better not be off-course. They have to land on a runway, right? So for us it’s the same thing. You have a certain amount of bars and then you have to be in a certain place. You can be off a little bit, but in certain places you can’t be off. Then you just go phrase-by-phrase through it all.

SH: How many times do you rehearse for something like this? I forget how long the movie is, but to keep up that pace for two hours seems tough. Is it simply like a normal orchestral performance?

DN: You rehearse it with the technology, with the movie. Some films have more music than others. I’d say Back to the Future is kind of average. We have two two-and-a-half-hour rehearsals. We usually get through the whole thing maybe twice. But most of these orchestras are really good and they come prepared. It’s similar to a normal orchestral performance, except the movie is playing behind the orchestra.

SH: Recently the trend of doing scores live to movies has become more popular. Not just older silent movie accompaniment, but contemporary films — I think recently they’ve done the Lord of the Rings movie scores in New York. Why do you think it’s trending upwards?

DN: I just did On the Waterfront a couple weeks ago. I’ve done West Side Story with the New York Philharmonic. They had a tour of On the Waterfront in Ann Arbor, Michigan two days ago. This is just a thing!

I think it’s a hybrid. It’s not really a pops concert and it’s not really a film music concert, per se. It has a lot of really positive aspects for an orchestra and their development. They’re always trying to get people to come. This is sort of a way to get people that don’t usually to come to the concert to go. And I think the live movie thing seems a little bit, frankly, easier to put together than a film music night even if there’s no film or, even worse, a clip night where there’s all the stuff that you have to find and license from the studios.

These single-film performances are all produced by somebody and then rented to these orchestras. They’re all ready to go. You don’t have to do anything. I mean, you have to pay money, but you have the scores and the film’s there and everything is ready to go. In a way, it’s easier. Also, it’s a little bit of a new thing. It’s not really a pops concert. It’s a dramatic performance. The orchestra become dramatists, like an opera. Or a ballet. In film the music isn’t as hegemonic as it is in ballet or opera, but still it’s sort of the same thing that we’re dramatists. We’re dramatizing a film. We’re all trying to make a film more understandable, entertaining, and exciting.

SH: Has Alan Silvestri had any input in the performances?

DN: Oh, yeah! I mean, like I said, we’re really good friends. Alan was there for the whole time in Lucerne when we put it together and he was there when we were at the Hollywood Bowl. And we tweaked some stuff and he’s been at a bunch of rehearsals, so he’s had a huge influence.

It’s fantastic because if you have a question, you just ask the guy who wrote it. Let’s say you’re doing some older film like West Side Story and there’s a problem. There’s no one to really ask, so you have to kind of work it out with everybody.

SH: That must be convenient, but also intimidating. But you said he’s your good friend, so I’m sure it isn’t that bad.

DN: Yeah, it’s not. I guess in a sense it might be intimidating, but it’s not really. We’re all just trying to make it the best performance with the orchestra that we can.

SH: There is supposed to be 20 minutes of new music added. Can you elaborate on that?

DN: It’s music from the other Back to the Future movies. Alan didn’t write any new music. So we’re purists about this. There’s no orchestral music for maybe 25 minutes into the movie in the original, so you have to think, “Well, we have the original composer and the director of the movie, can we work something out for the orchestra?” If not, the movie is running for 20 minutes before you hear a note of music. And so they worked it out and they spent a lot of time figuring out what to do.

So I can’t even remember it without music now, it’s so integrated. I think it’s great what he did. And again it’s pulling from the quote-unquote “canon” of Back to the Future.

SH: What other movies would lend themselves to a performance like this?

DN: I mean, there’s a million of them! I don’t even know where to begin.

It’s such a miracle that this is happening. Because normally when a film is done, parts and the scores, they’re not discarded, they’re just kind of thrown in a box and filed in some studio. So Back to the Future, Universal owns it. They just kind of store it and that’s it. Now there can be a musical afterlife that can actually make them some money and it’s wonderful publicity for these movies and these studios and it’s, as we say in Hebrew, it’s a mitzvah. It’s a nice thing to do for the public, you know?

The problem is the studios own all this stuff. They own all the paper that this was printed on. So you have to know how to do this. How to get it from them and get all the stuff you need to do this. There are literally hundreds, if not thousands, of movies that would be good live movies.

What we’re encouraging everyone to do now, at least in our community, is to not let the stuff get thrown away. Be careful with it and mark it and have it so that if somebody wants to do it live, there’s not a huge cost in trying to find it and redo it just because somebody didn’t store it properly.

SH: Well, yeah, that’s great. It’s good to do a perfect movie like this, like you said.

DN: Well here’s the best story.

So MGM in 1939 has Wizard of Oz, right? That’s their movie. MGM has this huge catalog of music and musicals and all this wonderful stuff, and at some point in the ‘60s, they took all that stuff and buried it in a dump that’s near the 405 freeway in Los Angeles, to make room for offices. Can you imagine?! Maybe that’s just me, but they took all that stuff and threw it away. Can you imagine what an original piece from Wizard of Oz would be worth now?

Nobody got this, because movies were a one-off. No one expected any of this music to be played ever again. But for me, because of my father, you know Alfred Newman was a huge part of the first generation of film composers. Him and Dimitri Tiomkin and Franz Waxman and Erich Wolfgang Korngold and Bernard Herrmann. These were the guys that figured out what film music was. People had no idea this would ever happen. For others it was just one time and move onto the next movie, you know?

So this is a really amazing phenomena. The only issue is how much stuff is available to play, because it’s expensive and difficult to put it together. All of us are working hard to figure out what movies are good to play live and get it pressed, so that it can be rented and played. Almost every orchestra in the world is doing a live movie. If you looked at every orchestra, at least in the United States, if not in Europe or Asia, at some point in their next 15, 16 seasons, there’s going to be a live movie! That’s a lot of orchestras.