Why 'Strange Days', James Cameron's Weirdest Joint, Isn't a Cult Film

Kathryn Bigelow's 'Strange Days' is everything 'Point Break' wasn't, which is not a good thing.

“Paranoia is just reality on a finer scale,” says sleazy music guru, slide guitarist, and abusive “wirehead” Philo Gant in Kathryn Bigelow’s 1995 film Strange Days. He’s talking to Faith, his nu-metal chanteuse girlfriend (Juliette Lewis). The remark initially scans like cogent pseudo-philosophy, but doesn’t hold up to a double take. It’s gibberish, which makes it an apt distillation of the James Cameron-penned film, which is quietly celebrating its twentieth birthday today.

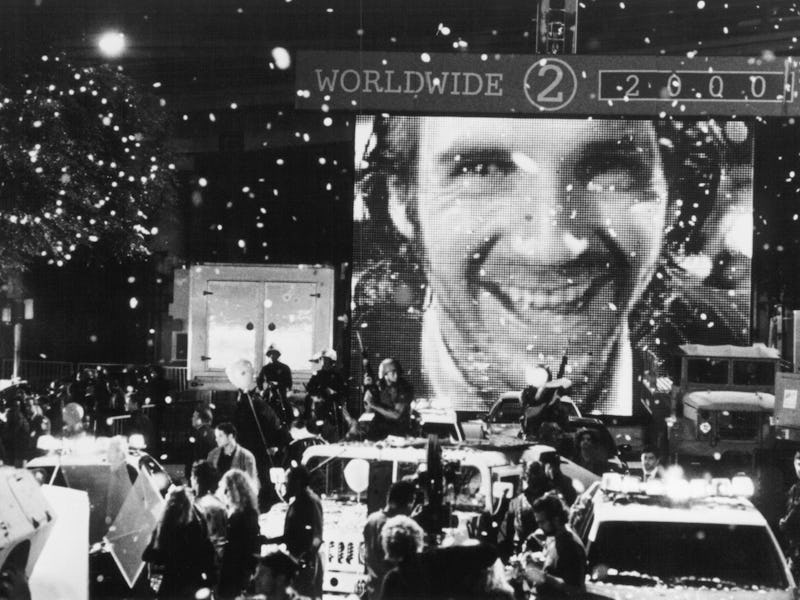

Strange Days was the perfect misbegotten, dystopian, two-and-a-half-hour flop to ring in the late-‘90s. It theorized the panic inspired by the idea of the “Y2K bug” before the concept existed, and perfectly embodied the braindead, high-concept drama of a decade that we still hate-watch. Days is also a definitive proof of screenwriter and producer Cameron’s complete lack of self-awareness. This film is hyper-pretentious madness, but also cliched. This wholly unsubtle style was only a few years away from solidifying into a wildly profitable anti-aesthetic.

In many ways, it seems like Strange Days should have blended into the cinematic landscape, and yet Bigelow’s massive project was certainly too weird and unmarketable to recoup even a quarter of its 43-million budget. There is plenty that is very puzzling about this film, just on paper. It takes at least the first hour (in which, mind you, nothing happens) just to process the casting: Ralph Fiennes as lovelorn dealer of virtual-reality modules and ex-cop? Angela Bassett as his golden-heart ass-kicking limo driver and sidekick? Juliette Lewis as Fiennes’ ex-flame and the female Gavin Rossdale? Tom Sizemore, as a shadowy P.I. and macho sex magnet with Fabio hair? One has to squint to determine if those are really Vincent D’Onoforio and William Fichtner as automatonish crooked cops left blessedly free of dialogue. The scene is set — precariously.

The more consistently pressing issue, though, is the things that these untenable characters say. “He uses the wire too much — gets off on tape not on you,” Nero tells Faith, and the police commissioner’s “ass is so tight, when he farts only dogs can hear it.” Virtual-reality junkies are “squidheads,” and getting high is “jacking in.” The awkward one-liners and overbaked explanatory monologues reflect, meaningfully, the film’s conceptual strangeness. Days is essentially a tribute to old-Hollywood noir masquerading as a post-Brazil epic, and Cameron, unsuccessfully, tries to channel and update the punchy, hardboiled dialogue of ‘40s and ‘50s detective films and the stories of Dashiell Hammett or Raymond Chandler.

Plenty of sci-fi writers since at least the time of Blade Runner have chased this ideal, but few have failed so extravagantly for 145 minutes.

Despite its “telling it like it is” feel, it remains very unclear what Bigelow’s movie is. There’s no Y2K-like theory in play, just vague foreboding. Paranoia is more background than plot point. The action revolves around a murder mystery: Lenny Nero (Fiennes) keeps receiving tapes from a mysterious assailant who is raping and murdering women while patching them into his SQUID virtual reality system so that they can experience his feelings as he kills them. Eventually, the crimes seem to be tied to a tape documenting the execution of rapper and activist Jeriko One. Nero and Mace (Bassett) aim to figure out what is happening, in part so Nero can save his ex-flame Faith from possible danger.

In the end, the crimes are not all tied to one conspiracy, and their ramifications are underwhelming. Don’t worry about parsing all this out, but Sizemore is trying to save Faith from being killed by Philo for what she knows about Jeriko One’s death — while he is working for Philo — so he kills Philo and attempts to frame Nero. The crooked cops who got mad and killed Jericho are just trying to cover their tracks after getting pissed and killing an activist who was publicly denouncing the LAPD. Sizemore’s character intimates late in the film that Nero and Mace “don’t know how far up the food chain this thing goes,” but ultimately the thing literally goes nowhere. There is no vast political conspiracy, and the future of the world is definitively not at stake. In fact, somewhere along the way, we lose track of exactly what the stakes are, and even what the thing is.

Could it be that all the pomp and circumstance has just added up to a fairly conventional crime drama? Fiennes is the anti-hero investigator, Lewis the femme fatale, Bassett the sidekick who is too good to be in the movie, and everybody else are the various video-game-like bosses they have to work their way through. Strange Days plays to weird angles, fooling us into thinking it’s something bigger than what it is.

What is most fascinating to me about looking back on Strange Days is how little our interests in sci-fi have changed today. The fear of the next big jump in technology — and its unfathomable side effects — is fundamental to today’s most critically beloved works of dystopia, from last year’s Ex Machina to the Black Mirror series. But in attempting to theorize the future, we tend to counterintuitively push back into the language of the past to find the language to do so, chasing the same old demons. Noir, as an archetype in entertainment, became codified around Cold War fears and the untold power of the H-Bomb, and the drama of every age needs some sort of boogeyman to give it weight. Many of these apparitions end up looking almost exactly the same.

Strange Days is one of the first and most ridiculous documents of turn-of-the-millennium paranoia — one of the more pathetic paranoias, historically — as well as a decadent and undersung example (others might include Red Rock West, U-Turn, The Spirit or, some might bet, the second season of True Detective) of the subgenre that might best be called “dumb noir.” It’s a shame you can’t stream it anymore; it holds up as one of the great jaw-dropping cult anomalies of its decade, and one of Hollywood’s most magnificent flops.