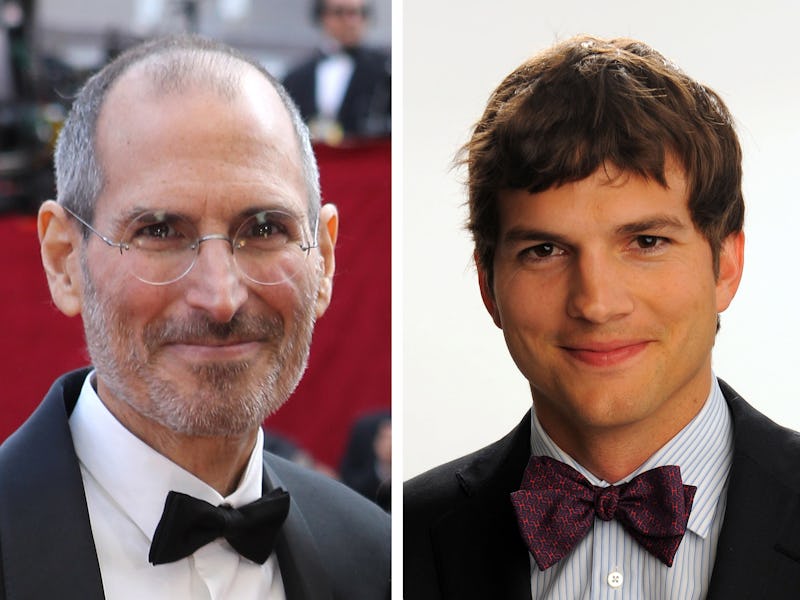

Farewell to Ashton Kutcher's 'Jobs'

Before 'Steve Jobs' comes to wash its memory away forever, a few brief comments on the first 'Jobs' feature film.

Aaron Sorkin and Danny Boyle’s Steve Jobs hits some theaters tonight, and all of them tomorrow. The buildup has been long and even suffocating: If the fact that this was an all-star team-up — featuring the most beloved and emergent actor of the past five years — with an all-star cast wasn’t enough, there were the revelatory Sony leak emails, which illustrated a behind-the-scenes drama that simply whets our appetite for the fruits of the dysfunction.

Amidst it all, the memory of the independent film Jobs, directed by Joshua Michael Stern (of Swing Vote fame) and co-produced by and starring the deathly unlikely Ashton Kutcher (directly before his tenure on Two and a Half Men), began to rapidly fade. Sure, it trended briefly on Netflix streaming — how otherwise would one come to watch it? — but it’s since passed into the site’s reserve stock, being “suggested for you” only after pages of back-scrolling.

Stern’s film was generally poorly received, but not very poorly — it was too nondescript — and didn’t do great, but also didn’t flop. The subject matter and ludicrous casting were too alluring. Perhaps, we thought, this would be the Jobs film.

What it ended up being is an unabashedly bullet point-y, unimaginative, and ultimately very boring film: a very stupid Jobs film for a world that is stupidly obsessed with Steve Jobs in stupid ways. The backstory behind the film sheds some light on why it is quite as Wikipedia-pagey as it is: Most of the possible and most relevant primary-source consultants passed on contributing to the film. Some of them (most notably Apple co-founder Steve Wozniak) did share information with Sony for the Boyle film.

Daniel Kottke did cooperate, a relative side figure who roomed with Jobs and his wife when the initial, infamous paternity denial took place, and was ultimately cut out of his share of stocks as an original Apple employee when Jobs took the company public in the early ‘80s. Thanks partially to Kottke’s testimony, we have half-assed and palpably reductive threads regarding Jobs’ long estrangement from his daughter (for which Kottke was on the sidelines), and a couple of totally vestigial scenes of Kottke (played by Lukas Haas), mostly looking sad or livid about Jobs’ behavior in a meeting.

It’s the disease that plagues many biopics when too many biased living parties’ perspectives are amalgamated (see also: Straight Outta Compton): Jobs’ plot, like Compton’s, gets bent out of shape to include tangential narratives or outright falsities, and the movie suffers deeply. The issues of structure and pacing in Stern’s film were so egregious that critics mostly blamed the crew and writers over the actors.

Generally, that would seem to be a fair assessment (the screenplay is credited to a person who never seems to have written anything else, and it shows). But let us not overlook Kutcher’s performance. It is a perfect example of the kind of biopic lead performance which attempts to blur the line between where motivated, embodied acting ends, and where deploying well-rehearsed movements and speech tics begins. A slightly more acceptable example of the phenomenon would be John Cusack as the ‘80s Brian Wilson in the otherwise excellent Love and Mercy, who engages the audience emotionally even as he seems to be just mimicking mannerisms he’s seen in video clips. It’s clear Kutcher did a lot of work to pinpoint a Jobs-ian walk — hunched-over slightly, with palms pressed together in a prayer pose when he’s thinking — but that, sadly, ranks among the most impressive elements of the performance. He’s memorized Jobs’ flat, slightly mannered tone, but uses the character’s deficit of emotional empathy as an excuse for sucking all dynamics out of the performance.

Dermont Mulroney, all hair, as Apple CEO and investor Mike Markkula

Kutcher’s portrayal makes so much sense in the context of the film, which interacts appropriately with its subject matter. Jobs is all surfaces, platitudes, and reductive idealism, elements which were fundamental to Jobs’ approach to leadership, marketing, and design. No scene sums it up better than Jobs meeting renowned Apple designer Jonathan Ive in the final act of the film, where Jobs begs Ive to design “anything” beautiful — to make some clear, useful, good-looking thing. Then there’s Kutcher-Jobs’ cartoonish fury over the Mac’s lack of fonts; it’s one of the film’s most laugh-out-loud funny scenes, but it’s unclear if it was meant to be.

Jobs projected a flat but automaton-ish front to the world that this film mimics in its every detail; in other words, it buys into Jobs’ dream rather than interrogating it in any meaningful way. Theorizing that the CEO’s approach to business and his dream of the “personal computer” was linked to his warped view of human nature is done only on the most embarrassingly basic level: essentially, through unsubtle, sub-Social Network monologues where people tell Jobs he’s a narcissist, and shots of Jobs staring at walls (or letters from his daughter) in his unfurnished Citizen Kane-lite mansion.

Yes, that is J.K. Simmons

Kutcher’s Jobs spits back a nice, jumbled compendium of the mythologies we as a tech-obsessed but under-informed world have about Steve Jobs, mixed with some scraps of detail from people who were there for some of it. People’s opinions tend to be strong on Jobs and Apple’s influence in general, and Kutcher and Co. pay fan service to all of them. The film doesn’t need to explain how Jobs evolves into a genius; he just is. You know, because it’s Steve Jobs. Things happened like they happened, and Stern, Kutcher, and the gang leave it to us to provide connective tissue. We accept that Jobs is going to get by by breaking all the rules because we already know the narrative’s ending, or because we know that that’s just what happens in by-the-numbers biopics like this. Stern and Kutcher sought to make their movie sleek and efficient, like Jobs made his products, but fell (sometimes hilariously) short of the mark.

Jonathan Ive (Gilles Mathey ) and Kutcher-Jobs

In some ways, though, its failure is interesting, so I hope that people will continue to puzzle over it on rainy days. Netflix: keep Jobs streaming!